Content warning: This story contains graphic descriptions of domestic abuse and racial slurs by the story's subject.

Twenty years ago, Jim Goad was Portland's hottest new writer.

When he gave a reading of his first book in May 1997, fans spilled onto the sidewalks outside Reading Frenzy, the downtown counterculture bookshop owned by now City Commissioner Chloe Eudaly. They were there to get a look at the 35-year-old author with a rockabilly bouffant and a heart tattooed on his sculpted biceps.

"There were people out the door, peering in the windows," he now remembers.

Goad was then a breakout name in Portland, where he lived for 11 years. The Temple University graduate arrived here with a bit of notoriety as the creator of a crass zine called Answer Me! that printed "ironic" essays in favor of rape and abusing women. In Portland, he wrote his first and most infamous book, The Redneck Manifesto, which earned him a $100,000 book deal from Simon & Schuster.

Early reviews of Redneck—which opened with a chapter called “White Niggers Have Feelings Too” and uses the N-word a total of 76 times—were mostly positive. Florida’s Sun-Sentinel called it a “furious, profane, smart and hilariously smart aleck defense of working-class white culture,” while Publishers Weekly said he was “writing at the top of his voice” and “merits a listen.” Kirkus Reviews wrote that while Redneck was “sure to infuriate the liberal reader, he is also likely to make that same reader laugh ruefully, and often.” WW praised the book’s “brutally candid critique of American race relations.”

Early reviews of Redneck—which opened with a chapter called “White Niggers Have Feelings Too” and uses the N-word a total of 76 times—were mostly positive. Florida’s Sun-Sentinel called it a “furious, profane, smart and hilariously smart aleck defense of working-class white culture,” while Publishers Weekly said he was “writing at the top of his voice” and “merits a listen.” Kirkus Reviews wrote that while Redneck was “sure to infuriate the liberal reader, he is also likely to make that same reader laugh ruefully, and often.” WW praised the book’s “brutally candid critique of American race relations.”

That book was the closest Goad got to mainstream success.

Twenty years later, Goad has become instead a leading figure in far-right fringe media. Best-selling author Michael Malice called him "godfather of the new right."

In 2016, Gavin McInnes, a co-founder of Vice Media who later founded the Proud Boys—a far-right men's organization whose members dress in MAGA hats and Fred Perry polos—called Goad "the greatest writer of our generation." McInnes lists The Redneck Manifesto as one of three "required" books on modern Western culture, alongside Pat Buchanan's The Death of the West and Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010 by Charles Murray.

"This is Proud Boy Holy scripture," reads a review of Goad's book on the Proud Boys' website. "This book could be our bible."

Goad's popularity during the Trump era has seen a resurgence. Goad says his former publisher doesn't give him figures, but The Redneck Manifesto's sales are accelerating. It's been through 17 printings, and its Amazon sales rank shot up 200,000 places between 2012 and 2017. It's currently the No. 30 top-selling book in "minority studies."

"People see that Trump got elected, and they want to know how this monster came to power," says Goad. "They come to me for the etiology of the disease."

Portlanders often view the alt-right that elected Trump as a phenomenon foreign to our city. But the "bible" of the Proud Boys was written right here. If you want to know where the angry white men of the alt-right came from, it's important to try to comprehend Jim Goad.

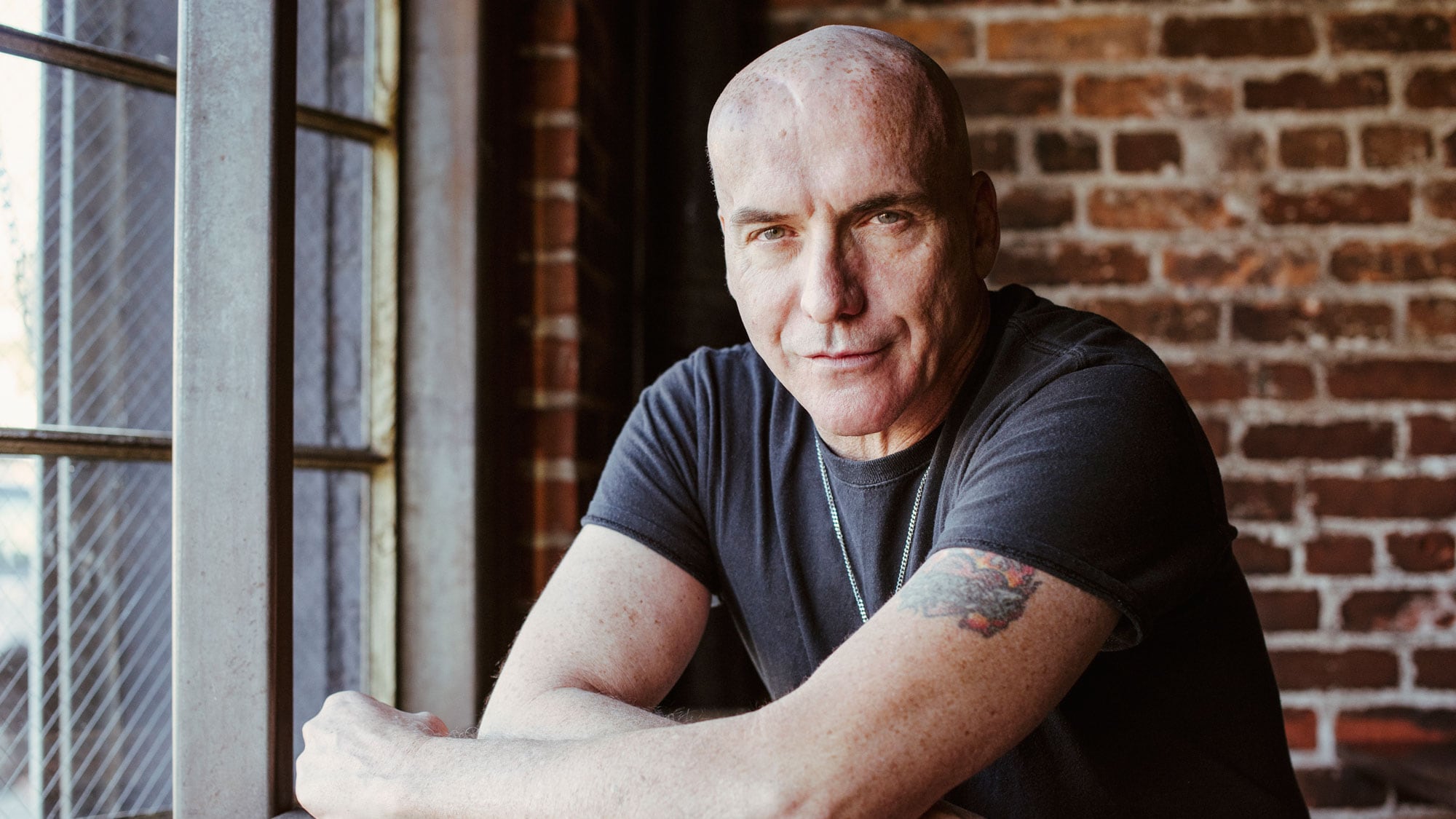

Goad, now 56, is divorced and living with a pit-bull mix named Bam-Bam in a rented room on the outskirts of Atlanta. He publishes a weekly column on Taki's, a right-wing blog, and writes dirty short stories for Thought Catalog. He also records a podcast—recent episodes include an interview with the editor of neo-Nazi website the Daily Stormer and Goad's rant about how the left "destroyed comedy." Though he is still writing books—his latest, The New Church Ladies: The Extremely Uptight World of "Social Justice", was published in February—he hasn't given a public reading in five years. After surgeries to remove both a benign tumor and his gallbladder, he has taken up yoga and a Paleo diet. His rockabilly hair has given way to a bald head and muted button-down shirts.

When pressed, Goad dodges all political labels and party affiliations, saying he's a "lone wolf." He claims not to consider himself part of the alt-right, though he did stump for Trump.

"Those guys don't like me because I'm not a team guy. I don't identify as right wing. They're wired that way, it's a team movement," he says. "I'm radioactive in ways, I'm beyond the pale."

That's not how established figures on the right see it. Michael Hoffman, a writer of anti-Semitic histories, praised Goad's ability to bring his revisionist history of "white slavery" to a wider audience.

"Redneck Manifesto is one of the first major breakthroughs for drawing attention to the suppressed history of the bondage of whites in early America," Hoffman tells WW.

In the new right's media universe, Goad is ubiquitous. He's been praised by nearly every major far-right website, from white nationalist Richard Spencer's AltRight.com to anti-Semitic white-identity blog the Occidental Observer to anti-immigration site VDARE.

VDARE founder Peter Brimelow, a former National Review writer whose book Alien Nation argues that America should stay as white as possible, had lunch with Goad not long ago.

"[He's] one of the brightest and bravest voices to emerge on the politically incorrect right," Brimelow tells WW. "His style is far too wild for the conventional pearl-clutching [Republican] types, and he's really too idiosyncratic to be part of any movement, but he will regularly make great and important arguments."

Jared Taylor, editor of white supremacist website American Renaissance, tells WW that Goad is "an excellent writer who treats taboo subjects creatively, incisively and with a sense of humor. He is always worth reading."

Goad, for his part, says people who call him racist are trying to hang him with "guilt by association," complaining that racism has become a catchphrase for "any white person who's OK with being white."

But along with insisting repeatedly that people labeled Holocaust deniers are just "quibbling over numbers" and white supremacists are mythical, Goad cites studies that say "whites are supreme in IQ tests by far" to blacks and Hispanics.

"Although I hold Mexicans in the highest esteem as a proud and noble (if exceedingly short) people, they tend to score poorly on standardized tests and have never invented much of note beyond nachos," he wrote in his column, in response to this year's controversy over Portland's Kooks Burritos, which shut down after its American owners were accused of culturally appropriating their tortilla recipe from Mexico.

Yet Goad has not been totally shunned by the mainstream.

He remains friendly with comedian Patton Oswalt, who opted to debate the election with Goad on a podcast last November. Oswalt defended his decision with effusive praise of Goad.

"The man can fucking write," Oswalt wrote on Facebook. "And, unlike a lot of the failed comedians and sad punks on the alt-right, he isn't in it for the 'lulz' and doesn't affect a bullshit nihilist pose."

But if Oswalt is still willing to consider Goad a worthy debate partner, he's poison to most who knew him in Portland. Attempted interviews with Goad's friends and former publisher here were stopped at the mention of his name.

That's not just because of Goad's current politics, but because of what happened here after the publication of The Redneck Manifesto.

At 5:45 am on May 29, 1998, almost exactly one year after Redneck was published, Goad left his girlfriend Sky Ryan bleeding on the side of Northwest Skyline Boulevard. When police found her, Ryan's left eye was swollen shut and her thumb had been bitten deep into the flesh. According to Ryan at the time it took 26 stitches to put her face back together, her face was fractured and it took three days for her eye to stop bleeding.

When police came for him, Goad's defense was that she had hit him first.

"She bops me in the nose," he says now. "Yeah, I beat the fuck out of her."

The couple had a long history of violence, and so did Goad. Previously, he'd admitted publicly to hitting his wife, Debbie. He had also filed for a restraining order against Ryan after a series of threats.

He remains unrepentant. "I know I'm supposed to say I was bad, but that's not how I feel," he says now. "That's why I'm so hated. People resent it when somebody has a little spine."

Four years before the abuse, he had written an essay, "Let's Hear It for Violence Toward Women!", which began, "Women are only good for fucking and beating. When you get tired of fucking them, there's only one thing left to do."

To prosecutors, this was evidence.

"Portland writer Jim Goad has long been accused of glorifying violence against women," WW's Maureen O'Hagan wrote at the time. "Now he's been charged with practicing it, as well."

The thing that saved Goad from a 15-year sentence was his habit of saving phone recordings, tapes in which Ryan threatened Goad that she would "stab you a million times" and "cut you up into a million pieces."

Goad was allowed to cop a plea, and served two and a half years.

While in prison, Goad says his worldview sharpened. He's since spoken of both how arduous the experience was and admiringly about how prisons function as an ideal society.

"In prison, people get along better than they do on the streets," he wrote on his personal website. "Convicts display the sort of camaraderie that only emerges under siege. They are polite to one another because they know the consequences of being rude. It's as if everyone's carrying a gun, so no one gets shot."

Goad came to believe segregation of racial groups in prison showed tribalism was natural. Though The Redneck Manifesto argued for class unity against the rich, Goad now says equality of races is a myth and that racial separation is the natural order.

"Everyone understood that they were tribal, and as long that was cool, everyone gets along," he said on a recent podcast describing his prison time. "Plus, Oregon was overwhelmingly white, so if you fucked with peckerwood you'd have an ocean of sunshine drowning you. If it was ambiguous who was in charge, that's when you got conflict. If there's one group completely in charge, things seemed to cool out."

The other thing that Goad decided while incarcerated? That his own suffering in jail far outweighed that of his victim. In his memoir Shit Magnet, Goad writes that he had no sympathy at all for Ryan: After all, he'd been assaulted, too.

"Incarceration," he writes, "is much worse."

When Goad got out of prison in late 2000, he was treated like a leper. Almost no one wanted to talk to him, he says, except Frank Faillace, owner of Dante's on West Burnside Street.

"Frank got a job, created a job for me when I got out of prison," says Goad.

He began by designing strip-club magazine Exotic, where he was later promoted to editor.

The book he wrote in prison, Shit Magnet, was devoted to Goad's toxic relationship with girlfriend Ryan while his wife was dying of ovarian cancer. It was published in 2002 by then-Portland-based Feral House after being rejected by every major publisher in New York, according to a 1999 piece in The Village Voice. That piece noted that Goad was "something of a local pariah" and called Shit Magnet "part autobiography, part self-justification, part screed."

Only eight people came to the June 2002 reading of Shit Magnet at bookstore CounterMedia, one of whom was Fight Club author Chuck Palahniuk, who has his own sphere of influence within the alt-right (see The Far Right's Strange Obsession with Portland Author Chuck Palahniuk).

"He doesn't pull his punches. Brutally honest without worrying about being correct," Palahniuk told the Portland Tribune when interviewed at the reading.

Palahniuk, Faillace and Eudaly are the only Portlanders Goad speaks warmly about.

"We used to go to pug play day in Irving park—he had Boston terriers," Goad says of Palahniuk.

Faillace still describes Goad as a friend and "fucking brilliant writer," but says they "respectfully disagree on a lot of things" and that the two haven't corresponded in a decade.

In an email to WW, Eudaly says her store had a policy at the time of accepting all books from local authors or publishers, without regard to content. But she says if she were running a bookstore now, she wouldn't host a reading by Goad.

"There's no way in hell I would host any author that would draw a crowd of the kind of creeps and fools that populate the alt-right," she writes. "It isn't something I'd subject my staff, my customers, my community, or myself to. That's not censorship, it's personal choice."

In the years following his domestic abuse conviction, Goad complained about the increasingly "cold reception" he got from most of the writing community in Portland. "Where I come from, tolerating ideas is probably the most precious kind of tolerance," he says. "But not in Portland."

Goad says he was "silenced" here. Specifically, starting in 2004, his decision to wear an Iron Cross necklace caused him to be confronted by an anti-racist skinhead group called the Rose City Bovver Boys.

In 2005, a friend suggested Goad leave Portland to write a book about NASCAR. He was ready to go. Goad never finished the NASCAR book but landed in Georgia, working as a copy editor and making pamphlets for a medical company. He went two years without a single paid writing gig.

Goad might have faded into obscurity were it not for Gavin McInnes, a longtime admirer. McInnes, recently departed from Vice Media, brought Goad aboard as a writer for a then-obscure website called Taki's.

Goad wasn't sure they'd have him. He confessed his criminal record and that he'd been to prison. It wasn't a problem.

"That's OK," said his new editor. "We've all been to jail here."

Though the alt-right may have started as a fringe movement, it's now seized a level of prominence unthinkable a few years ago—or at least unthinkable to most Portlanders.

Goad says he's not surprised to see the rise of Trump.

"I think the left really overplayed its hand with identity politics," he says.

In a post titled "Smells Like Victory," penned Sept. 16, 2016, Goad predicted Trump would win the election on the backs of "a huge brooding swath of Americans out there who know that the media despises their very existence."

"A Trump victory would be a deathblow to the media and political establishment," he wrote. "That's a good thing. A Trump victory would also lead to massive collective depression and rampant suicidal ideation in all the people that I genuinely hate."

As a political stance, this is hardly better than utter nihilism. But 20 years after it was written, The Redneck Manifesto is an eerie harbinger of the seething white resentment that now fuels a part of the American right.

"Working-class whites are denied any identity beyond a guilt rap," Goad wrote in 1997. "So don't act surprised when they form an identity merely on being hated and scapegoated. As opportunities for unskilled labor vanish, white trash is likely to get nasty. And politicized in ways that make you squirm."

But according to many on the left and center of the political spectrum, Goad's not just chronicling that resentment: He's amplifying it.

"Goad incites fear, and fear, of course, is a primary driver of hate," says former Portlander Joshua Frank, who co-edits left-wing magazine CounterPunch. "Goad's convoluted ideas about race pose a real danger because his own followers, like so many on the alt-right, will tell you they aren't racists when their actions would clearly tell you otherwise."

In the past, Goad's works have triggered fringe types, conspiracy theorists, and the simply unhinged.

In 1994, Francisco Duran fired 29 rifle shots at the White House, leaving an issue of Goad's zine and a hand-scrawled quote from Goad in his van: "Can you imagine a higher moral calling than to destroy some one's dreams with one bullet…." Duran was eventually convicted of attempting to assassinate President Bill Clinton.

Two years later, three teenage British neo-Nazis killed themselves after reading Goad's essay about suicide; one left Goad her life savings so he could continue his work.

And the Charlottesville rally, where Heather Heyer was killed and hundreds of men marched to the chant "Jews will not replace us," was organized by a onetime member of the Proud Boys, founded by one of Goad's chief admirers, Gavin McInnes. (McInnes did not respond to requests for comment.)

Goad's inflammatory writing is rightly protected by the First Amendment. But Goad refuses all moral culpability for what others do with his books.

"There are a lot of strangled hookers because of a misreading of a passage on the Whore of Babylon," Goad says. "Blame ends with the actor. If I tell somebody to go kill somebody and they're dumb enough to do it, I think they should go to prison, not me."

Goad is unmoved by claims that his writing—or that of other writers on the radical-right fringe—might share some blame for inciting the violence in Charlottesville and on the streets of Portland. He blames instead the leftist counterprotesters who he says are trying to shut down free speech.

"Goad, [and] so many on the alt-right, proclaim to be champions of free speech but sure as hell hate it when their marches are met with overwhelming resistance," says Frank. "Does Goad have a right to speak his idiotic mind in a public space? Of course he does, but we also have a right to challenge him and drown out his fearmongering."

Related in this issue:

The Far Right's Strange Obsession With Portland Author Chuck Palahniuk

What's the Hardest Part About Being a Black or Brown Person in Portland

From the Archives: Jim Goad in Willamette Week

"The ANSWER: Not Guilty," From Our February 7, 1996 Edition

Suicidal Tendencies From Our March 6, 1996 Edition

"Scariest: Angry White Male," From Our Oct. 30, 1996 Edition

"The Untouchables," From Our June 4, 1997 Edition

"Goad Rage" From Our June 17, 1998 Edition