Portland Book Festival’s in-person day of panels, readings and conversations unfolded under a textbook perfect Portland sky—overcast but dry, brisk but warm. After last year’s completely virtual festival, this year’s felt hesitant and carefully considered.

PBF promised to keep crowds under 75% occupancy, and the day unfolded easily. Attendees from previous years will remember the veritable soup of readers one could expect—thrilling, if overwhelming. The day’s lines were short, all but the line for the Gastro Obscura vending machine.

Here’s a rundown of the rest of the day:

Voices From the Pandemic

Moderated by Oregon Public Broadcasting’s Geoff Norcross, the Voices From the Pandemic panel presented The Oregonian’s Eder Campuzano, Oregon Public Broadcasting’s Amelia Templeton and The Washington Post’s Eli Saslow, discussing topics surrounding Saslow’s recently published nonfiction collection of the same name.

Saslow didn’t read from his work. Instead, Norcross volleyed questions at the three local reporters, all of whom actively report on the COVID health crisis. It was a great discussion: lively and thoughtful, exactly what one attends panels for.

The audience learned that Templeton struggled reporting during the pandemic because it was often necessary to report the same story over and over. “Journalists want to tell new stories,” she said. Some of her work during that time required her to brainstorm: “How can I keep coming back to the stories that really matter, even if they’re repetitive?”

Campuzano reports on education for The Oregonian and found that during the pandemic, where he might normally wait at the end of the school day to interview parents and students, he got a wider survey of subjects via a Google form. On the form, he left a check box for parents who didn’t want follow-up conversations: “Check this box if you want to give me a feeling of what you’re going through,” he said, but he estimated that out of 500 respondents only 50 chose that option.

“People called me back at a rate they never have before,” Norcross said, in agreement.

Templeton said she felt there’d been a real missed opportunity when it came to things like ivermectin coverage. “Laughing at people taking horse medicine” wasn’t the best approach, she said. “Ivermectin is an anti-parasitic, and it works really well as an anti-parasitic. But COVID isn’t a parasite. We missed an opportunity to educate people.”

While the panel was illuminating for audience members interested in details about local reporting, one surprising consensus came after a discussion about misinformation.

During the panel’s Q&A portion, an audience member asked if journalists should be licensed. The question came following a disheartening conversation on the speed and veracity with which misinformation spreads. The audience member wanted to know if controlling who could call themselves a journalist would help with the situation.

Everyone seemed in agreement, maybe it would. And no one on the panel raised a concern about asking journalists—whose job it is to challenge power at all levels of society—to be accountable to whomever would issue such credentials. It was shocking that no one asked: Who issues the licenses?

Lovability

We found another riveting conversation in the second panel we attended—between Oregon’s poet laureate Anis Mojgani and poet Emily Kendal Frey, who won an Oregon Book Award for Sorrow’s Arrow in 2015 and whose collection Lovability was published by Fonograf this past July.

Frey has a patience and humor not always anticipated from a poet. When a cellphone rang at the end of their reading, they smiled and closed the book. “Exactly,” they said. Then: “I hope that’s my mom’s phone.”

The conversation between Mojgani and Frey wasn’t bound by much structure. The two friends conversed about poetry until Frey felt they could best answer something with a poem, which happened often—a lovely approach.

Frey related some frustration that so many of their poems still focus on childhood. “When I started writing poetry, I thought I would write a lot of poems about gazing out of a window or the sea,” they said wryly. “But nope, you don’t get to choose.”

Mojgani related that while Frey was working on one of Lovability’s longer pieces, they posted pieces of it to Instagram. Mojgani screen-grabbed the poem and was still in possession of the poem in that form, on his phone. We wondered if he would sell them as nonfungible tokens.

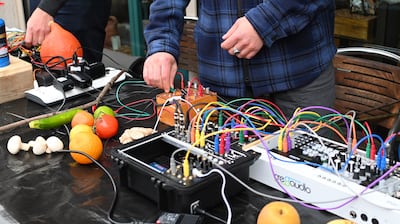

The Gastro Obscura vending machine

The festival’s most popular attraction was undoubtably the Gastro Obscura vending machine—a machine dispensing strange delicacies like Akabanga, a Rwandan condiment that is so spicy it’s served using an eyedropper.

Promoting the recently published Gastro Obscura: A Food Adventurer’s Guide, a sort of Atlas Obscura for food co-authored by local writer Cecily Wong, the colorful machine drew a line before it even began service, at 2 pm in the museum’s sculpture garden. Minutes into its operation, the line stretched down the block and around the museum. At 3 pm, someone near the front yelled to the end of line that they should all give up. There were too many people and not everyone would have an opportunity to purchase steamed bread in a can or pickled watermelon rinds. True to word, the machine stopped vending—quite strictly—at 5 pm. By then, the sky was dark and locals were scurrying to their homes—or to bonfires, dinners and music shows.

There’s still a chance to hear some of the conversations, even if you couldn’t see them in person. The panels at the 2021 Portland Book Festival were recorded by OPB for Literary Arts’ The Archive Project. A number have already been uploaded and more will be added in the coming days.