The good news, Oregon State Medical Examiner Dr. Sean Hurst recently told lawmakers, is that the jump in Oregon’s alcohol-related deaths in 2020 flattened in the first half of 2021.

The bad news: Drug overdose deaths, particularly those involving fentanyl and methamphetamine, soared to new highs.

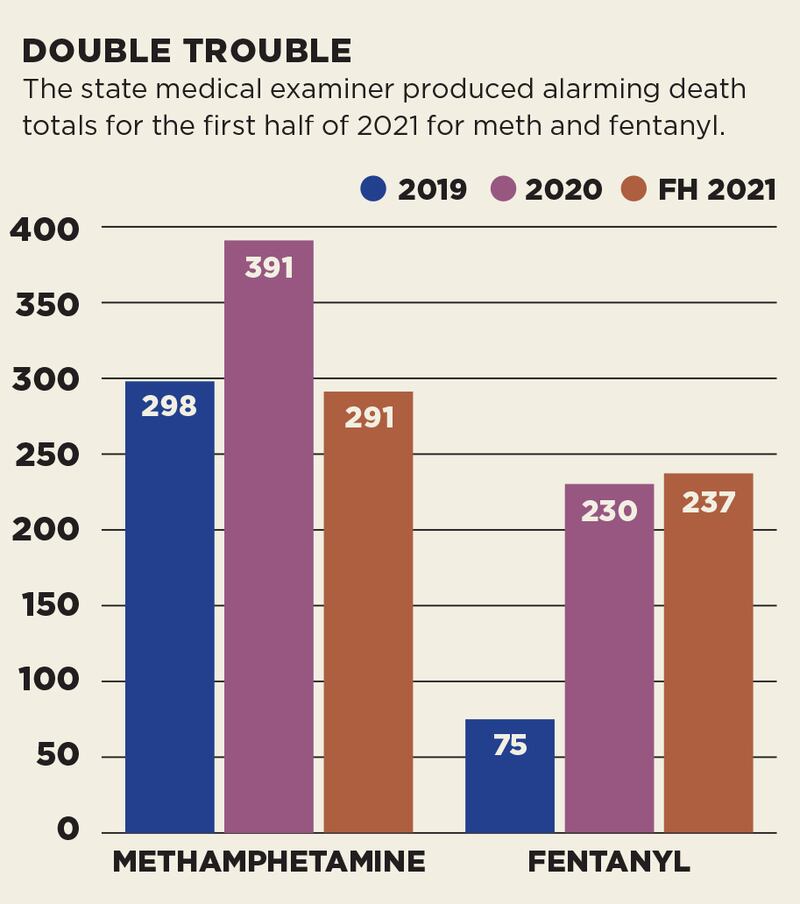

Deaths attributable to meth jumped from 2019 to 2020, and are on pace for a bigger increase in 2021, Hurst told lawmakers Jan. 13. Though slightly less numerous, fentanyl-related deaths are rising much faster: They more than doubled from 2019 to 2020 and are on pace to rise steeply in 2021 (see chart).

Together, medical examiner figures show, the two drugs will account for the deaths of more than 1,000 Oregonians in 2021—that’s nearly three per day.

“Substance use disorder is prevalent and it’s everywhere,” says Tony Vezina, chairman of the Oregon Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission.

Hurst presented his dismal news on drug deaths as the state races to implement Measure 110, the 2020 ballot measure that forced two major policy shifts. It decriminalized the possession for personal use of many hard drugs, including heroin, meth, cocaine and some opioids. Measure 110 also shifted funding from Oregon’s cannabis taxes—well over $100 million a year—to fund new referral and treatment services for substance use disorder.

The rise in overdose deaths started well before the passage of the decriminalization measure. The federal National Survey on Drug Use and Health for 2020, released last month, paints a grim picture for Oregon. As a state, we are second in the nation, behind only Montana, in terms of the percentage of people with a substance use disorder and ranked dead last in terms of access to treatment.

Measure 110 is supposed to change both of those indicators for the better. But the toll that meth and fentanyl are taking on the state is making it challenging for supporters to demonstrate the benefits of Oregon’s first-in-the-nation decriminalization effort.

“This is a big experiment for our state,” says state Rep. Rob Nosse (D-Portland), vice chairman of the House Behavioral Health Committee. Nosse supports Measure 110 but says Hurst’s death figures scare him.

He notes that decriminalizing drugs before referral and treatment services were in place created a costly gap: “I worry that we’re not getting our arms around fentanyl and the new kinds of methamphetamine that are out there.”

Many law enforcement officials opposed Measure 110 two years ago, warning of dire consequences if it passed.

In response to such concerns, the measure included a provision for police to write tickets for drug possession rather than make arrests. The idea was that those cited for possession could avoid a fine by calling a phone number on their ticket; that connection would open a gateway to evaluation and services—and get up to $100 of their fine waived.

Data collected by the Oregon Judicial Department from February 2021 through Dec. 31, however, shows that avenue has not worked. Police wrote 1,826 tickets last year for hard drugs (nearly two-thirds for meth) but few—only 55 for the whole year—prompted users to telephone the number for services. (The Oregonian first reported sparse use of the hotline last year.)

Most metro-area law enforcement agencies didn’t bother with the tickets. Police in Clackamas (11), Multnomah (108), and Washington (37) counties wrote fewer total tickets (156) than police in Douglas County and fewer than half the total citations in Josephine County.

Portland Police Bureau spokeswoman Terri Wallo Strauss says the state’s largest police agency simply lacks the staff to respond to the increase in violent crime and traffic fatalities, handle routine calls, and also write tickets for drug possession.

“Illegal drug use is a significant problem in our community. We recognize the challenges faced by people who are addicted and those who are self-medicating and have mental health issues as well,” Wallo Strauss says. “But the truth is that we are not the police department we used to be, and some services we used to provide are not happening as much as they should.”

Ken Sanchagrin, executive director of the Oregon Criminal Justice Commission, which analyzes crime data, has looked at the ticket numbers. He’s heard a variety of explanations for the geographic disparities, including differing workloads and varying priorities from agency to agency. He’s also pondered whether there’s a connection between the big overdose death increases and Measure 110. He’s wary of drawing one.

“It is too early to tell, and it will take time to conduct a rigorous causal analysis on the data,” Sanchagrin says.

“While it is plausible (and certainly logical) to assume that at least part of the increase could be due to BM 110,” he adds, “the real question will be to what extent that relationship exists given the other trends that are occurring nationally.”

Hurst, the medical examiner, agrees, noting other states are also experiencing large overdose increases. “Oregon’s experience with drug-related mortality is consistent with trends in other jurisdictions and in the United States as a whole,” he says.

Rising overdose deaths are not a new phenomenon in Oregon. The rate of fatalities from meth, for instance, has climbed steadily since 2016, more than doubling in that time.

Advocates of Measure 110 say it will take time for the benefits to become apparent, as was the case in Portugal, which decriminalized hard drugs in 2001 and saw its overdose death rate plummet-—but only after services were in place.

Tera Hurst, executive director of the Oregon Health Justice Recovery Alliance (and no relation to the medical examiner), says voters signaled they wanted an explicit shift away from treating people with substance use disorders as criminals and to instead direct energy and money toward treatment.

She says it’s unsurprising that citations are not driving drug users to seek help. She and other advocates did not expect they would. Even arrests rarely motivated users to seek treatment, they say—most go only when they are ready.

Hurst says the more important and beneficial outcome of Measure 110 is that cannabis tax money has begun to flow to harm reduction (such as needle exchanges, naloxone and wound care), housing and other services.

“That money has really allowed organizations to expand their reach,” she says.

So far, the Oregon Health Authority, which is overseeing the implementation of Measure 110, has distributed $31 million in grants to a variety of service providers. Hurst notes that about 9,000 people a year were getting arrested for drug possession before Measure 110 and more than 15,000 have voluntarily sought various kinds of help funded by the Measure 110 grant money. So, she says, the measure is beginning to work.

OHA is now in the process of allocating $270 million more in funding for treatment of substance use disorder for the next two years.

Vezina, the Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission chair, says he’s pleased to see the health authority rapidly moving cannabis tax revenue toward new services, but he wants to see state officials treat substance use disorder with the same urgency as the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I get daily updates on COVID—down to the number of presumptive cases. But I don’t get daily updates on substance abuse disorder or overdoses,” Vezina says. “We need metrics to make sure we’re putting money in the right places.”