After a year of preparation, amid threats and counterthreats between the prosecutor and a squad of pro bono lawyers working with the American Civil Liberties Union, the two-week ANSWER Me! trial came to an end on Feb. 1.

A Bellingham, Wash., jury acquitted two booksellers of felony charges of distributing lewd material for profit for selling the controversial 'zine ANSWER Me! #4, which is published by Jim Goad of Portland. The ANSWER Me! series is intentionally shocking, with previous issues devoted to such subjects as serial killers and suicide victims ("Q&A," WW, Dec. 6, 1995).

As always, Goad was gracious in victory: "The government's predatory behavior in this case is indistinguishable from sexual predation, going after the littler, weaker enemy, trying to force their will upon them."

Though clearly a victory for free-speech advocates, the acquittal left many questions unanswered—and it was not the vindication of the 'zine for which some had hoped.

The acquittal, jurors said after entering their verdict, had nothing to do with ANSWER Me!'s literary merit but was based on the more technical question of the prosecution's failure to prove that the defendants had knowledge that the 'zine was obscene.

"They were divided on the value of it," said defense coordinator Breean Beggs, "and that's why they got down to knowledge. They said, 'Well, regardless of what I think of the magazine, [the defendants] didn't know.'"

"The jury really understood that these two booksellers were being put in an impossible situation—to somehow predict what one prosecutor might think was

obscene."

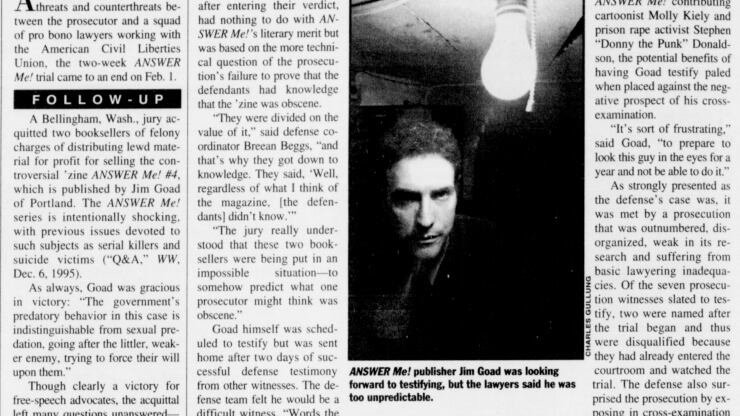

Goad himself was scheduled to testify but was sent home after two days of successful defense testimony from other witnesses. The defense team felt he would be a difficult witness. "Words the defense lawyers used," Goad recounted. "were 'hotheaded,' 'uncontrollable,' 'unpredictable.'"

Given the successes the defense had with witnesses such as ANSWER Me! contributing cartoonist Molly Kiely and prison rape activist Stephen "Donny the Punk" Donaldson, the potential benefits of having Goad testify paled when placed against the negative prospect of his cross-examination.

"It's sort of frustrating," said Goad, "to prepare to look this guy in the eyes for a year and not be able to do it."

As strongly presented as the defense's case was, it was met by a prosecution that was outnumbered, disorganized, weak in its research and suffering from basic lawyering inadequacies. Of the seven prosecution witnesses slated to testify, two were named after the trial began and thus were disqualified because they had already entered the courtroom and watched the trial. The defense also surprised the prosecution by exposing in cross-examination a prosecution witness' conviction for misappropriation of property.