On May 1, 1992, Rodney King addressed the LA riots with a televised speech. He was suffering from brain damage inflicted by the LAPD, and he had spent the previous three days watching TV news footage of people dying in his name. His attorneys, who hadn't let him testify at the trial in which the officers who beat him were acquitted, had written a speech for King to read. King improvised his own.

"It's one of the great American speeches," says Roger Guenveur Smith, whose one-man show Rodney King comes to Portland this week. "Immediately people started cutting it to that part where he says 'Can we all get along?' It became the butt of many jokes. Even Rodney King said that his own children used it against him"

But at the end of Rodney King, Smith performs the speech in its entirety. Smith first performed the show in August 2012, two months after King was found dead in his swimming pool. Smith will perform the show for the last time here in Portland, a week before a Spike Lee film of a Rodney King performance from last August goes up on Netflix. Lee and Smith's prolific artistic collaboration stretches back to Do The Right Thing (Smith played Smiley), and they've already made a film of another one of Smith's many one-man plays about black historical figures, A Huey P. Newton Story, which originally aired on PBS.

But Netflix has an even broader demographic than public television, and certainly a wider reach than theaters. "Usually, you would only get those people who were interested in pursuing this avant garde solo performance thing," he says.

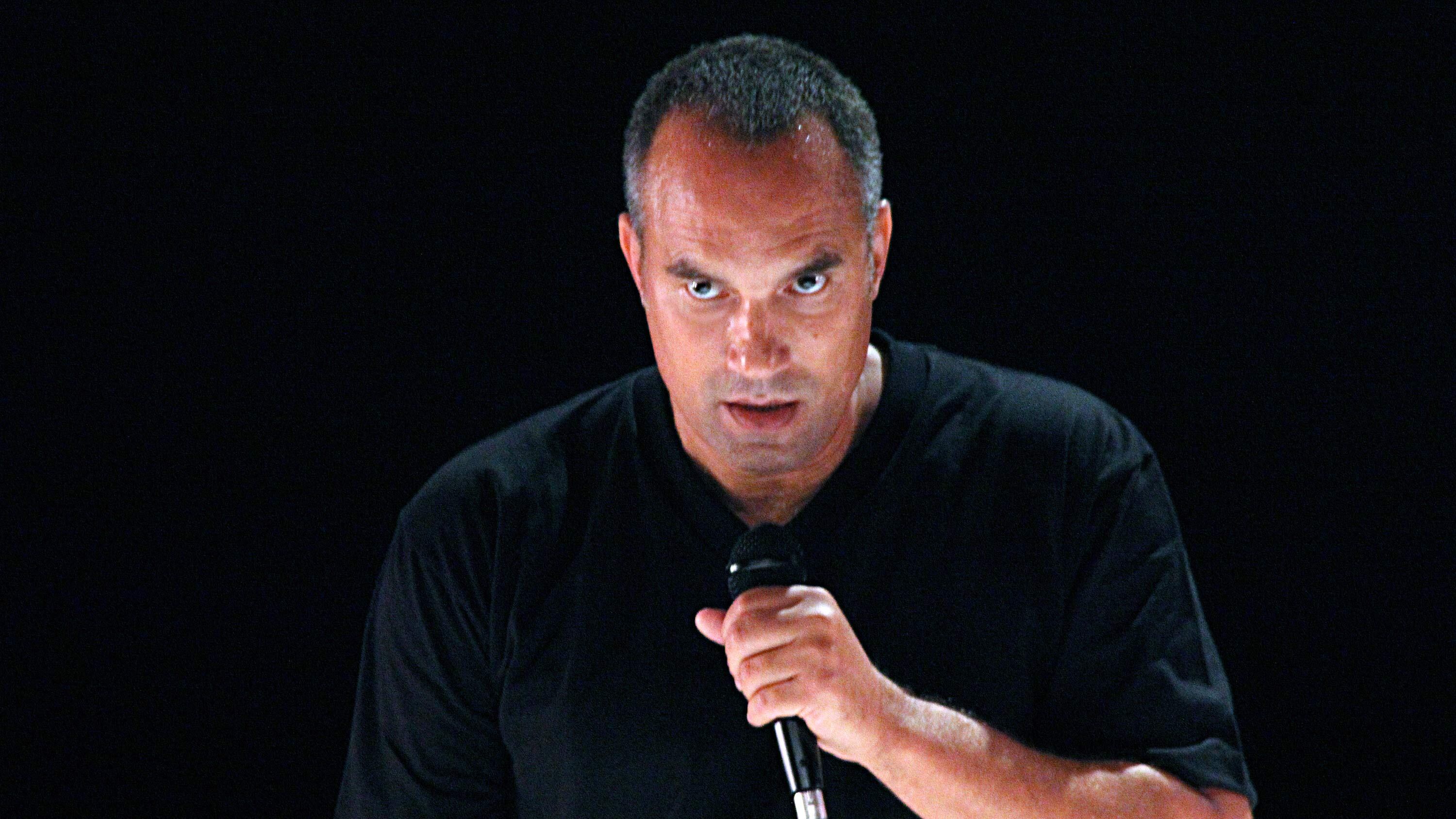

Created by an Ivy League-educated theater artist and a history academic, Smith's work is definitely high concept. But it's not esoteric. Within the confines of a small stage that's an illuminated, white rectangle, Smith performs Rodney King barefoot with a microphone as his only prop. The play ends with King's speech, but starts with Willie D's "Fuck Rodney King," an anti-pacifist anthem with lines like "You can't lead the black struggle/ And be friends with the enemy." In between, Smith fervently rolls out poetic lines that evoke moments from King's life, from his childhood, to his brutal beating by the LAPD, to his struggle with public attention and addiction, to his death at 47.

Though the play was born out of what Smith calls "disciplined improvisation," it had to be scripted for the film. On the hottest day of the summer, it was shot in one take.

Talking on the phone from his home in LA, Smith sounds relieved to move on from Rodney King. "Telling this tale has not been the easiest thing," he says. "It takes a lot out of me."

He rattles off what King suffered: at least 56 blows from metal batons, two shots from a Taser emitting 50,000 volts of electricity. "He was kicked, abused, it was televised," says Smith. "And those offices we saw abuse him were acquitted of basically all charges."

Then, there's the estimated 56 people who died in the riots following the acquittal. "For each blow, one person died," says Smith, "none of them police officers." A man was strangled in a grocery-store produce aisle. A woman went out to get bread, "caught a stray bullet. Boom." King personally knew Reginald Denny, who was pulled from the truck he drove and beaten nearly to death as TV cameras rolled. "[King had] to absorb the story of Reginald Denny being beaten to a pulp in his name," says Smith. "It's an unbearable weight that he took on."

Which, to Smith, is part of why King's speech is so remarkable. "Rodney King could have righteously gotten up there—I think anyone would say, even his detractors—and said 'Burn it down.'"

King didn't do that, but he also didn't stop at "Can we all get along?" either. "He answers it at the end," says Smith. "He says 'yes we can, we can get a long.'"

To Smith, that resolution is crucial. It's still not asking for "bullets for bullets" like Willie D, but it's remarkably less passive: King was telling, not asking, his country something. "I've been calling it the gospel of Rodney King," say Smith, "Which boils down to 'Hey, we're all stuck here for a while, so let's work it out.'"

SEE IT: Rodney King plays at Artists Repertory Theatre, 1515 SW Morrison St., artistsrep.org. 7:30 pm Friday-Sunday, April 21-23. $15-$30.