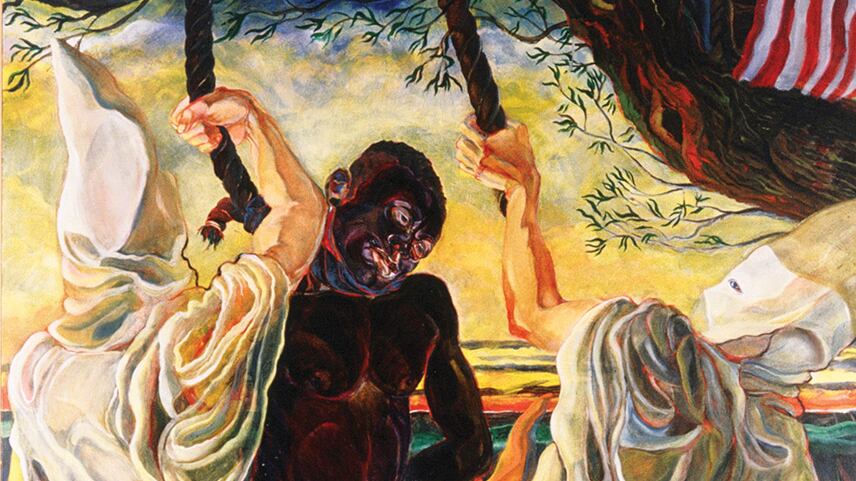

The first painting you see when you enter Arvie Smith's exhibition at the Portland Art Museum features a black man, stripped of his clothes, being lynched by hooded Klan members, with someone in the corner of the frame waving the American flag.

Smith renders images of racial violence and oppression on a monumental scale—with some canvases as large as 7½ feet tall by 6 feet wide—so it can be painful to stand in front of them. It can bring up shame, embarrassment, disgust. I had to see the show twice, because the first time I went, I kept looking at the photos of the paintings I had just taken on my phone instead of looking at the paintings themselves. I struggled with the realization that I wanted them to be smaller, easier to deal with.

Smith paints in a highly romantic, florid style that belies the content of his compositions. And his use of soothing tones—warm browns, reds and oranges—creates further dissonance between what we first see and what reveals itself when we allow ourselves to absorb it. Smith's work is densely packed with symbolism, caricature and commentary.

Hands Up Don't Shoot, a painting that references the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., depicts a smiling Aunt Jemima holding two platefuls of buttered flapjacks as her town burns behind her. A chalk outline in the distance holds the shape of a man killed while surrendering. In the foreground, opposite a Confederate flag, a white camera operator films the scene for our entertainment and his profit.

In another painting, Smith faithfully re-creates Edvard Munch's The Scream, replacing Munch's ghostly figure with an open-mouthed Buckwheat, America's most bankable pickaninny caricature. Painted across the canvas are the words "we be lovin' it," a take on McDonald's "I'm Lovin' It" campaign that spawned a series of racist commercials in which characters rapped for "urban" audiences about the new dollar menu. Smith's piece is a layered critique about how the fine-art world excludes the very same people whose subjugation is readily exploited for commercial gain.

"I speak unfettered of my perceptions of the black experience," Smith says. "By critiquing atrocities and oppression, by creating images that foment dialogue, I hope my work makes the repeat of those atrocities and injustices less likely."

We are accustomed to appreciating art that inspires and delights us, but it is a considerably greater task to reckon with work that makes us uncomfortable. Smith reminds us that one of art's noblest purposes is to challenge, to get us to stare at our mistakes, misdeeds and mistreatment of others square in the eye.

Smith's show feels even weightier now than when I saw it months ago. In the 10 days following the Nov. 8 election, the Southern Poverty Law Center tracked 876 incidents of discrimination in the United States, including "multiple reports of black children being told to ride in the back of school buses." The images in Smith's paintings are not simply a commentary on the past. They are harbingers, too.

Art has a way of starting conversation like nothing else. Let Arvie Smith's masterfully painted canvases draw you in. Then all you have to do is muster the courage to look at them.

APEX: Arvie Smith is at the Portland Art Museum, 1219 SW Park Ave., portlandartmuseum.org. Extended through March 12.