The longest a U.S. prisoner has been held in solitary confinement is 43 years. It's an impossibly long time to be deprived of human contact—according to the United Nations, placing someone in solitary for longer than 15 days counts as torture. To curator and experimental filmmaker Vanessa Renwick, even the U.N.'s standard is inconceivable.

"I feel like I would go insane in a day," says Renwick.

In 6×9: A Virtual Experience of Solitary Confinement, you're in a VR solitary confinement cell for only nine minutes. The first VR project by The Guardian, 6×9 is now at Outer Space Gallery as part of Welcome to Your Cell, an exhibit that Renwick curated.

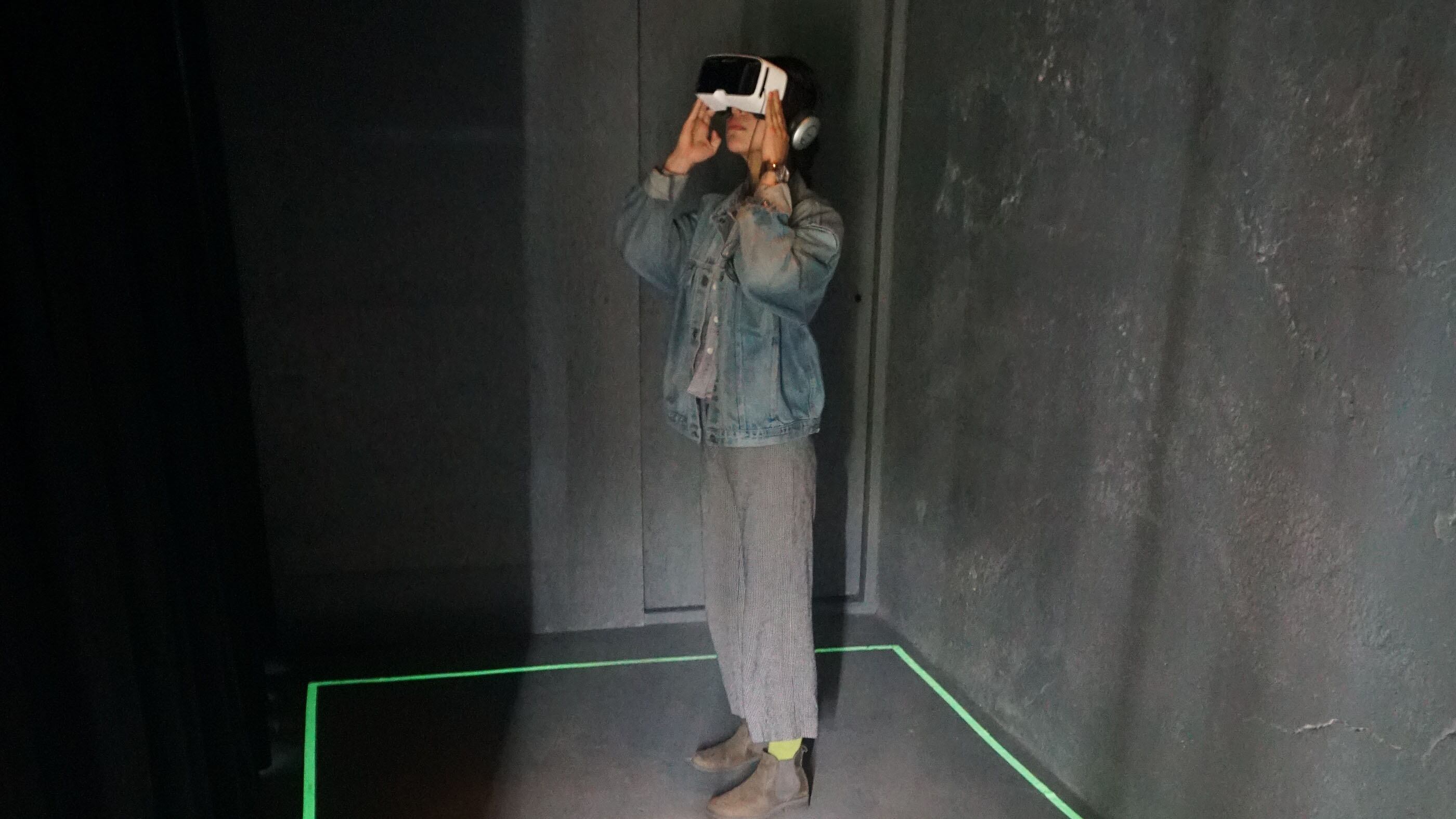

Operating in a tiny converted garage in the King neighborhood, Outer Space Gallery is roughly the size of two solitary confinement cells. For Welcome to Your Cell, the walls are painted black. There's an illuminated 6-by-9-foot square projected onto the gallery floor, which marks where to stand as you put on a VR headset. The only other light source is the second piece in the show, a video called Hakim's Tale by Philadelphia artist Erik Ruin. On a white background is a black paper cutout portrait of Hakim Ali, who was in solitary for two years, and who began advocating the end of the punishment after his release from prison. The video is narrated by Ali, who recounts his experience. "I literally lost it," he says. "You go into a world that's hard to describe."

As Hakim's Tale progresses, torn scraps of paper begin to close in around Ali's portrait until the screen is completely black. It ends on an almost hopeful note, however. Ali tells us that while in his cell, he found Allah, which gave him at least some form of connection. Still, he makes no pretense that religion is a viable antidote. "Those that can't get that back, they're just lost forever," he says.

Welcome to Your Cell gives plenty of statistics about solitary confinement. Before 6×9 begins, white letters floating in a black void inform visitors that between 80,000 and 100,000 U.S. prisoners are currently held in solitary confinement. Gallery brochures offer information about organizations working to end solitary and improve the lives of prisoners.

But the show is more concerned with conveying the horrifying experience behind the facts. "The education that I got from these two pieces has really stuck with me more than reading a book or watching a conventional documentary," says Renwick. "I felt that they were so well done that more people should experience them, and that maybe that would lead to bigger discussions and more actions happening."

That particularly comes through in 6×9. A warning appears in the VR void of 6×9 before the program begins. You barely have enough time to read the first sentence, "Images may be disturbing," before the lengthy disclaimer disappears. VR is disorienting, which 6×9 leverages. When the program starts, you're standing on a narrow cot in a grimy, cinder-block cell. In the echoing narration by disembodied voices, a psychologist cites high rates of self-harm, and a former prisoner recalls an eerie floating feeling. Words appear on the walls around you, listing offenses that can land you in solitary like "looking at a corrections officer the wrong way" and "having too many rolls of toilet paper."' Eventually, the overlapping voices escalate into a fuguelike cacophony. In the most dizzying moment, the program lifts you up to the ceiling. You look down at the cell from above before it zooms you back to the floor on the other side of the room.

If you walk around in the virtual cell, it's easy to bump into one of the gallery's walls. In 6×9's most disorienting moments, it's sort of comforting to know you can put your hand against something stable. Unless, of course, you end up reaching for a virtual wall to brace yourself, in which case you'll end up only more dissociated.

Renwick says that prior to discovering 6×9 at a film festival, she was actively uninterested in VR. No one can rightly call Renwick's tastes conservative—the Portland filmmaker has a long career of experimental, fearlessly irreverent work—but there was something unappealing to her about experiencing a fabricated world through a headset rather than on a screen. "It's part of my goal when I make work and when I go on tour with it, that I'm experiencing it with a lot of different people, or that people are experiencing it together," she says.

But in 6×9, the disconnect from your surroundings is part of the point. "Usually, when you think of VR, you think that you're going outward and into other very expansive, trippy universes," says Renwick. "This felt so isolating to me. It seemed like such a perfect medium in that way. You put it on, and it's just really blocking everything out, and it's just about you yourself and your experience, not your reality."

Renwick's insatiable desire to connect through art may explain her careerlong interest in art made by prisoners, and about the consequences of depriving someone of those kinds of connections. But it's more accurate to say her desire to understand and experience rather than explain is what makes her a worthy conduit for the subject.

Fittingly, Renwick doesn't claim to have answers, just catalysts for empathy. "I'm still learning," she says. "I'm not a prison activist. I'm just an artist who was like, these pieces are incredible, and more people should see them."

SEE IT: Welcome to Your Cell is at Outer Space Gallery, 3726 NE 7th Ave., outer-space.us. 6-10 pm Friday, 1-8 pm Saturday-Sunday, May 18-20. Free.