One thing you could never take away from Thor Lindsay were his ears.

His body may have otherwise failed him—his lungs finally succumbed to years of abuse, and possibly overuse, on July 16, at the age of 59—but his ears he could always rely on.

They're what allowed him to grow Tim/Kerr Records, the label he started out of his living room, into the most prominent Portland record label of the '90s. And they're what set the sound of the city for the next two decades.

He heard the pop potential in Everclear and the Dandy Warhols before anyone else, releasing the debut albums that would quickly get them called up to the majors.

Related: "The story behind Everclear's Sparkle and Fade—and why everyone hates the man behind it."

At a time when every executive was searching for the mythical "next Nirvana," Lindsay worked with the actual Nirvana to burnish the legacy of the Wipers, Portland's greatest punk band. And when Kurt Cobain, at the height of his rock stardom, wanted to record a spoken-word noise record with William Burroughs, Lindsay was smart enough to put it out.

In between, there were more modest successes and outright failures, but no one ever questioned his taste. Whatever else there is to say about him—and there's plenty—Lindsay knew how to listen and make others excited about what he was hearing.

Of course, that's only one part of keeping a successful label alive. When Tim/Kerr eventually crashed, burned and faded into history in 1999, in many ways, Lindsay did, too. Even for those who knew him well, he became something of a ghost—floating in and out of the lives of his friends and family, haunting yard sales and Safeways and beer-league softball games. When he died last week, the local press hardly took notice.

But for the artists who owe him their careers, and the employees he inspired as much as he drove crazy, he's remained impossible to forget, for his flaws and charms alike.

"He was a spaz," says Dandy Warhols frontman Courtney Taylor-Taylor. "He was excitable, manic, had no impulse control whatsoever. But we all loved Thor. You couldn't not."

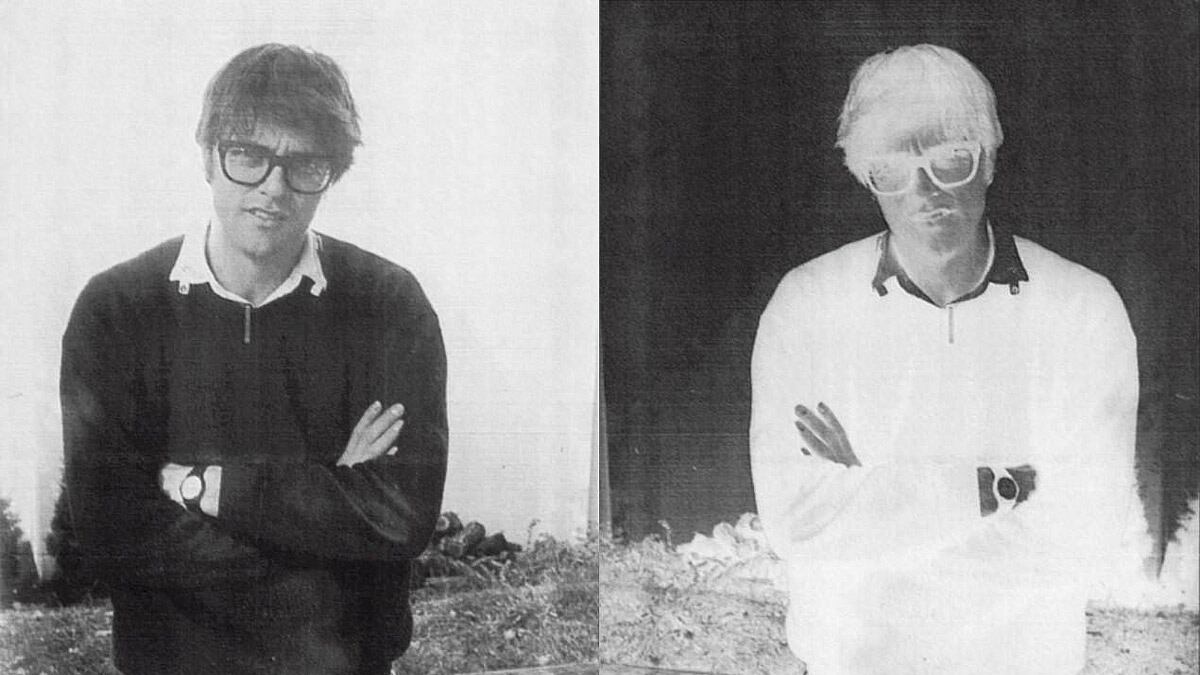

Almost from the moment he arrived in town, in the late 1970s, Lindsay displayed a determination to do something. On the run from a rough home life back in Minnesota, where he grew up, he immediately asserted himself in the fledgling Portland punk scene, playing in bands, working at early clubs and selling records from his massive personal collection at shows. An unrelenting jabberjaw, with a mat of mussed dark hair and thick, black-framed glasses that gave him the look of a '50s beat poet, Lindsay stood out as the resident goofball within a small circle of junkie nihilists.

"He wasn't like some search-and-destroy guy, smashing bottles or falling around drunk," says Jerry Lang, leader of bottle-smashing hardcore legends Poison Idea, who'd end up putting out several albums on Tim/Kerr. "Everybody has their whatever in the scene. There's the Greg Sages, who were like the artists. Then you have, like I said, the Sid Vicious guys. Then you have the Thor guys who were more collegiate, and know everything about every record. He was that guy."

In 1978, before he was even old enough to drink, Lindsay confirmed his geek credentials by opening a record store, Singles Going Steady, in the tiny downtown storefront now occupied by Sizzle Pie. Stocked with the most cutting-edge inventory in the city, the store became a hub for the developing punk community—all 80 or so members of it. It was there where he met Tim Kerr, a fellow vinyl enthusiast flush with family money. Lindsay convinced Kerr to become a silent partner in the business, a role he apparently took literally: Always a recluse, Kerr never gave interviews, and in recent years has retreated to the point where no one seems to know how to get in touch with him.

After the store ran its course, closing in 1983, Lindsay needed another outlet for his fanaticism. An opportunity soon presented itself: Gus Van Sant, then perched between a career in film and music, was looking for someone to put out recordings he'd made with the poet William Burroughs. Sensing a niche waiting to be filled, Lindsay, again backed by Kerr's financing, pivoted toward a label, then simply called T/K.

"This was a time in Portland where there were a lot of bands and not a lot of labels," says longtime friend Xj Elliott. "So he saw that as a need in Portland, and being somewhat of a business-minded person, depending on how you look at it, he thought this would be a good business opportunity."

Operating out of his house on Southeast 15th Avenue and Powell Boulevard, T/K was, for the first few years, a side gig for Lindsay, who split his time between producing shows for Monqui and working for a pro-audio company. That changed swiftly in 1992, first with the release of the tribute set Eight Songs for Greg Sage and the Wipers. Spurred by Nirvana's cover of "Return of the Rat," the compilation piqued the attention of the industry, which was clamoring for anything involving Kurt Cobain. Having learned of the label's history with Burroughs, Cobain then asked Lindsay if he could put him in touch with the poet. The resulting collaboration, a single titled "The 'Priest' They Called Him," featuring Cobain's gnarled guitar over Burroughs' deadpan reading, became the best-selling item in the T/K catalog, and led to a deal with Geffen to reissue albums from some of their other acts, such as the Posies and the Raincoats.

The Priest They Called Him from Eliana Nava on Vimeo.

With the increased exposure, the label opted to change its name to Tim/Kerr, to avoid a lawsuit from a defunct disco imprint, though that created other problems: Tim Kerr is also the name of a prominent Texas punk musician with Northwest ties, who campaigned, incessantly and unsuccessfully, to have the label change its name again.

///

Suddenly, running Tim/Kerr became a full-time job. While other Portland labels, like Cavity Search and Cravedog, popped up in the wake of the alt-rock boom, none had Tim/Kerr's, nor its eclecticism. In addition to cult favorites like Pere Ubu and the Bush Tetras, the label also worked with acoustic folk master John Fahey, experimental jazz keyboardist Wayne Horvitz and Seattle power-pop group Super Deluxe. After breaking Everclear and the Dandy Warhols, two of the most commercially successful acts to come out of Portland, Lindsay's reputation as an expert talent scout spread throughout the industry. Billboard wrote that, with him at the helm, Tim/Kerr "appears poised to become a major player among the indie labels of the '90s."

Many assumed the label had to be thriving. But as the business expanded, moving into a legitimate office space on Southeast Hawthorne, with a dozen staff members on the payroll, Lindsay's handle on the label's finances slipped—if he ever had control of that part of the business at all. An anonymous source quoted by The Oregonian estimated Tim/Kerr had lost a quarter-million dollars by 1997. If Kerr's money was a safety net, it was still made out of shoestrings.

"I mean, the whole thing was smoke and mirrors right from the get-go," says music publicist Carl Hanni, a former T/K employee. "Thor was a hustler, in both senses of the term. He worked really hard at whatever he did. But he also had that Three-Card Monte aspect to him, too."

Eventually, the illusion became unsustainable. A deal with Mercury Records, which would have given Tim/Kerr access to big-league distribution, fell apart in only seven months, the circumstances of which remain muddy. At that point, the bottom began to crumble. Employees left, and antipathy grew among the roster—especially after Lindsay bought a house while still owing many of them royalties.

Two years later, in 1999, the label shut down. Lindsay moved the remaining inventory into a storage facility. When he stopped paying rent on it, leftover T/K stock turned up in droves at the Goodwill bins out in Milwaukie. The Dandys ended up having to buy their masters back from the owner of a local record store.

Some still wonder if Tim/Kerr's undoing was malfeasance, stubbornness or some combination of both. Others believe that, for Lindsay, the label had simply become too big to succeed.

"I think he was overwhelmed by it," says Kt Kincaid, who lived with Lindsay when he launched the label and worked there off and on until the end. "The same thing happened with Singles Going Steady. Once it got to a certain level, I don't think he felt comfortable. It's that thing where you want something, and you want to be good at it, but maybe you're not really meant for it. Maybe you're not meant for things to be that big."

But if music-industry deals left him exhausted, his enthusiasm for music never dampened. Six months ago, Jerry Lang ran into Lindsay at a yard sale. Frail, bearded and in failing health, Lang didn't recognize him at first. Then they got to talking about a compilation of Portland bands Lang was putting together.

"All of a sudden, he had this huge smile on his face, and I can tell it reignited that record thing in him again," he says. "It was like it reanimated him. It was almost scary, like he got shocked. It was really cool, to know he loved music that much, even at the end."