One morning in the fall of 1984, I arrived at WW's offices on Southwest Stark Street to find a manila envelope tucked under the door.

Inside the envelope was a typed manuscript. The author made an astonishing claim: He had spent 10 days living inside the Central Oregon compound belonging to the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh.

For three years, the arrival of the Rajneeshees had been the state's biggest—and strangest—story. They appeared in 1981, seemingly out of nowhere, wearing garnet and orange robes. They purchased thousands of acres in rural Wasco County, transforming the Big Muddy Ranch into a bustling town, Rajneeshpuram, complete with fire department, airstrip and restaurants.

And they pledged loyalty to the Bhagwan—an Indian guru who had taken a vow of silence, but not before telling his followers that they could transform themselves with chanting, convulsing and hard labor.

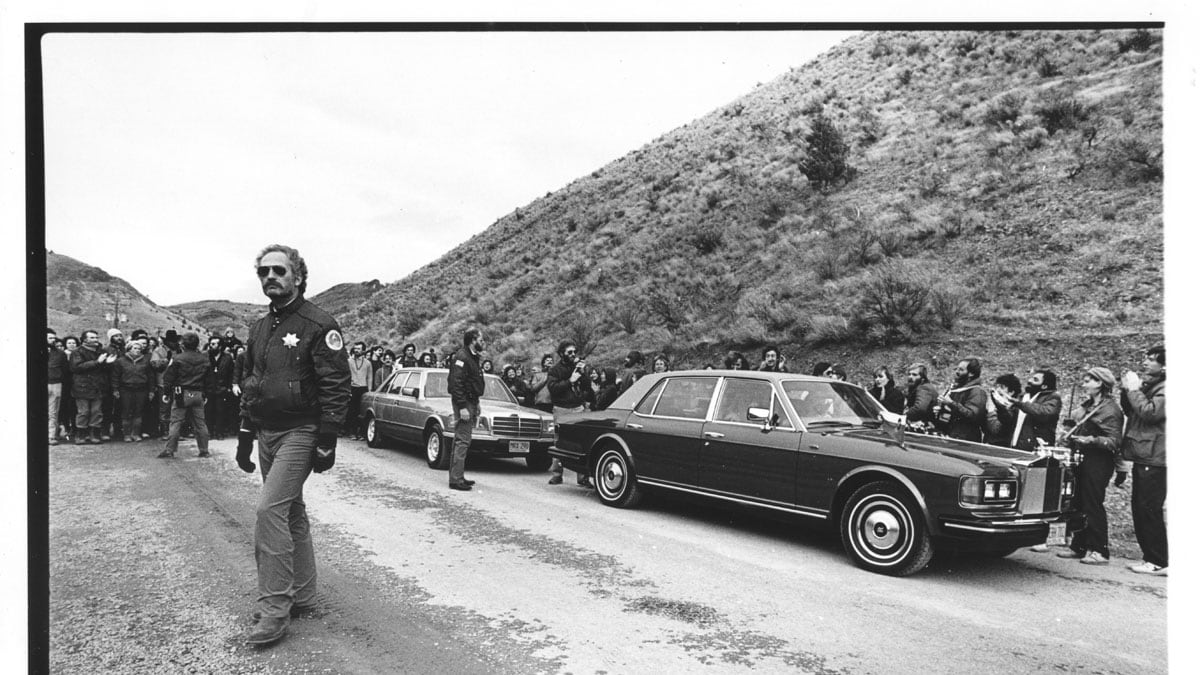

The Bhagwan was a messiah for the Me Decade. He didn't tell his acolytes to reject material possessions. Instead, he said the path to enlightenment could be found through enjoying physical pleasure so regularly that it became meaningless. He followed his own advice, owning a fleet of Rolls-Royces that drove him across the Oregon desert hills. And the followers? Word of their frantic meditation and all-night orgies was the talk of Portland.

Yet for Portlanders, the Rajneeshees presented a dilemma. Most of the guru's acolytes were affluent, college-educated progressives, and Rose City residents had more in common with them than with the God-fearing, gun-toting ranchers who wanted the newcomers out.

It was hard to get a bead on the situation. WW had reported on the conflict—including a 1983 bombing that set fire to Portland's downtown Hotel Rajneesh. But as an alt-weekly less than a decade old, we were working with a shoestring staff, and couldn't dedicate a single staffer to the odd goings-on in Rajneeshpuram, instead asking several reporters to pitch in on what was the most fascinating story of the first part of the '80s.

At the time, the goings-on had been especially strange.

That summer, the Rajneeshees began welcoming busloads of homeless people from skid rows across the country in a vain attempt to expand their political control. That fall, Rajneeshees poisoned salad bars at restaurants all over The Dalles, in an effort to incapacitate voters. More than 750 residents were sickened (45 of them went to the hospital) in what is considered the largest bio-terror attack on U.S. soil. The following year, a number of high-ranking Rajneeshees plotted to assassinate Charles Turner, the U.S. attorney for Oregon, who was investigating the group.

Thirty-three years later, the Rajneeshees are back in the spotlight.

A new Netflix documentary series, Wild Wild Country, details—in highly entertaining fashion—the scope of the group's aims. Viewers get a full picture of the Bhagwan, his breathless followers and the tactics of a ruthless plotter named Ma Anand Sheela.

In the fall of 1984, few journalists had a clear idea of the full nature of this group. (I had met both Sheela and the Bhagwan very briefly and had no better handle than others as to the true extent of the Rajneeshees' duplicity.) The Oregonian devoted enormous resources to covering the Bhagwan and broke a number of important stories about Rajneeshpuram.

We generated a lot of coverage. But the story on my doorstep, by Richard Fleming, seemed to get closer to the truth.

Read the original, two-part series by Richard Fleming here and here.

The story showed readers what was going on inside the compound: zealots who couldn't explain what they believed, desperate men pulled from poverty who brought their demons to the desert, and Maoist self-criticism sessions in which people confessed disloyalty and were rewarded with a bus ride back to the streets.

In the following pages, you'll read a sampling of what Fleming reported. We've also found other samples of WW's coverage from that time—including an interview of Sheela by our own Katherine Dunn, who just a year later would publish Geek Love. And we take a peek at what Rajneeshpuram looks like now.

It was a remarkable time in this state's history. And I'm proud to show you our part in it. MARK ZUSMAN.

Our report from inside Rancho Rajneesh on Nov. 19, 1984

Paradise Now

BY RICHARD FLEMING

Early in the morning. The old school bus lurches over the gravel road toward the soft glow cast into the October darkness by Rajneesh Mandir Temple, the main gathering place for the followers of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. Our bus is the first to arrive for dynamic meditation. Leaving shoes at the long row of glass doors at the entrance way, we walk quickly over the cold soft-tiled floor of the hangarlike building and group around an electric heater near the sign-in table. Steadily, a trickle of orange- and red-clad figures spreads color through the dimly lit interior. People talk softly in groups of three or four or sprawl on the floor to unlimber for the session.

As I stretch my sluggish limbs, I think back on the 10 days since I arrived in Rajneeshpuram as one of the homeless taken in by this religious community in the arid hill country of Central Oregon. The very act of remembering, I remember with a smile, shows I am a newcomer here. Rajneesh tells his disciples (called sannyasins) to live only in the now, in this very moment. The past and future are of no consequence. Everything of importance is going on this moment. Simply respond to that, he says, and you will be truly alive.

I haven't gotten the hang of that yet, so I let the worthless past rush out of the cold half-light of the morning's moment and replay for me its odd revelations.

"ET-10, ET-10—I know where that is—up close to where I live. Come on." The big black man strides away up the gravel road. I hustle to catch up. The streetlight near the information booth at Walt Whitman Grove dies into the late-night darkness. The Milky Way arches across the night.

"How long you been here?" I ask him.

"About a week. Come from the Bay Area."

"What do you think of this place?"

"It's cool. It's cool. Just some dudes want to fuck it up.[…]Pissing off the porches of their cabins. Throwing garbage around. Fighting. Had some real trouble up here the other night. Some dudes tried to rape a woman. Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Bad news. They're blowing it. This ain't the streets. This here's a fine place. Just fuck-king up."

We find ET-10, the last plastic-shrouded plywood hut in its section. The spare interior of the tentlike shelter already holds three men—the maximum.

The night's been long and is getting longer. I've been photographed, quizzed about education, job history, medical history and the government benefits I'm receiving. I've been issued a white plastic bracelet that identifies me by name and shelter number. I've been showered, disinfected for skin parasites, and relieved of my clothes for "unitization." I've been given an orange bead to wear around my neck for nine days to signify my quarantine from sexual contact until I'm certified disease-free by the community's medical staff. I've been issued two turtleneck shirts—one pink, one maroon—a thermal undershirt, a pair of red athletic-looking pants, and a black-and-red flannel shirt. They were out of jackets in my size, but I'll be getting one, they tell me.

At the information booth, I eat a peach from the sack lunch given to each new arrival. An older sannyasin with a gray beard and German accent jumps into a van and drives off to locate a sleeping place for me. Twenty minutes later he returns and takes me to a group of small A-frame cabins.

He motions to a cabin whose door stands ajar. The interior, done in varnished pine, is just big enough for three single mattresses to lie side by side, a footwide aisle between them. Two sets of small closets, bookshelves and cupboards flank the door. There is an electric heater, a wall-to-wall carpet, and a window opposite the door, which also has a window. It's obvious this A-frame is much better inside than the boxy shack I was assigned to initially.

A man with a long gray beard and gray hair sits on one of the mattresses and smolders with annoyance. With his glasses and wide girth, he looks like a street-hardened Santa Claus. I introduce myself as I unpack. He pulls on a battered orange jacket and says his name is Walt. He mumbles about people disturbing his sleep and pushes open the door to step outside for a cigarette.

I crawl beneath the clean sheets and sleeping bag that cover my foam-rubber mattress. In a few minutes Walt returns, sheds his coat and black hightop sneakers and groans down to his mattress.

"I haven't been able to sleep the past few nights," he says, his voice as resonant as a radio announcer's. "Got this damn cold. Then people keep coming in and bothering me." He gives me a sidelong glare, then continues undressing. "You'll like it here," he says. "Don't worry. The Rajneeshees treat you good. They have good food here—oh, too much rice…ugh, that rice. Rice and lettuce and tomatoes. They serve that stuff all the time…." Disgust swallows his words.

"They ripped me off, cleaned me out," he cries. His lanky body shakes as he takes a short sobbing drag on his cigarette. Walt and I stand next to him on the gravel path in front of our A-frame in the early evening twilight. "When I was workin', they cleaned out my cabin," he explains, "all my clothes, my shoes, all my stuff. Then—then I'm at dinner and somebody rips off my jacket. I just got it yesterday." His throat is so tight with sobs he can hardly talk. "So I—I report it," he says, "and they tell me, 'Well, maybe you shouldn't be here if you get so—so—upset.'" He shakes his head and looks up at the few stars, drags on his cigarette again.

Walt says, "Just a minute," and goes into the cabin. He returns with two pairs of socks and hands them to the guy. "They're extras. I don't need them," Walt mutters. The guy mumbles thanks and trudges up the path to his empty hut.

Bobbie's our other roommate. He's young, charged up, from Texas. He always talks loud and fast, laughing through a gap of missing front teeth, his hands circling his words in the air like flies buzzing around picnic food.

He likes to go to the Bhagwan's drive-by because of the girls. "Let me tell ya," he says, sweeping the lit cigarette from his mouth, "today ah was standin' next ta these chicks in the drive-ba line an' they were rally gittin' inta it. Sangin' an' dancin' an' smilin'. So that helps me git inta it too. So ah'm clappin' mah hands an' doin' a few moves, an' we're havin' fun there, an' when his car gits close, ever'body gits rilly excited, ya know—rilly whoopin' it up, an' so the Bhagwan goes ba this one chick, an' she's so happy she grabs me an' starts huggin' and kissin'. Ah mean, ah was lak this [smiles like a drunk and staggers back a step]. Ah mean, that was a-l-l-l-raight! Ya guys oughta come 'long next time."

The drive-by is a culture shock to me. Every day from 1:45 to 2:30 pm, several thousand sannyasins and street people line up to "celebrate" Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh as he idles by in one of his Rolls-Royces. From a distance, the line sounds like a gymnasium where a number of high schools arc holding pep rallies. Every 30 yards or so along the line, a group of singers or musicians are doing something loud to honor Rajneesh. Since everything is impromptu, some sannyasins may strike up "The Way of Bhagwan" or one of the other infectious little Rajneesh tunes, while a short distance away, a group of celebrants wielding percussion instruments are pounding out feverish stampedes of rhythm that overrun the brain of the casual bystander and drag his twitching body into the heat of festivity.

Overseeing the event is a cadre of maroon-skirted security women who offer frequent suggestions on appropriate behavior. "Stand in single file, please; Bhagwan wants to see everyone's face." "Please stay in line." "Don't dance behind others, please." "I'm sorry, visitors must stand behind the pink ribbon. Thank you."

As the Rolls approaches, the sound from each knot of musicians and singers jumps up the decibel scale. The frenzy of affection rising from the people jars against the steely-eyed suspicion of the rifle-bearing bodyguard walking just behind the Rolls.

From behind his closed window, Rajneesh lifts his dark, slender hands from the wheel and slightly chops the air to the music—Mitch Miller gone Zen. His lips are pressed into a subtle smile that seems to say, "I like you crazy people, but you keep flinging sweat on my windshield." I never see him look at anyone's face; his gaze seems to fall somewhere between his hood ornament and eternity. After attending a few more drive-bys and observing the same thing, I decide the single-file line is actually to allow the bodyguard to snappily punch the ticket of any National Rifle Association poster boy who infiltrates the line to show Bhagwan how common, ordinary American guns can repel red invaders.

A woman photographer, escorted by a swami (male sannyasin) from the community's press bureau, stalks the line, several Nikons hanging from her neck, looking for that certain glint of religious fanaticism that spells "cover shot."

The Rajneeshees are open to press coverage and allow reporters from all over the world to roam the community. But all are kept on discreet rein by press-bureau escorts who steer them around "security sensitive" areas, like Rajneesh's residence.

The press is eager to talk to street people, who for the most part are eager to give their opinions of the place. In the dinner line, a young black man from Chicago says, "I'm gonna be on ABC. Hope my friends back home catch me on TV. Now I been interviewed three times. Other day, I talked at that press conference. They was all throwin' questions at me and flashes going' off…." His eyes shine with the dazzle of the moment.

The dinner line is long. Every night it grows as more buses roll in. It takes a good half-hour to get in the door.

Dinner always includes a salad bar of fresh lettuce, sprouts, tomatoes, and a rotating selection of one or two other freshly harvested vegetables. The main dish is always interesting, mainly because of its unfamiliarity. Tonight it is a concoction of wheat, soybeans, and seasonings that tastes remarkably like beef stroganoff. Even the texture of meat is there. Everybody's wolfing it down.

On the cafeteria bulletin board is a news story from The Oregonian that puts the number of street people here at 2,300, more than double the figure given last week.

The meal lines are twice as long, so maybe it's true. There is also a notice that a general meeting will take place this afternoon for both sannyasins and street people. Everyone is to gather following the drive-by.

For an hour, people stream into the meeting room and seat themselves on the floor until several thousand have assembled. Then a dark-skinned woman dressed in scarlet shirt and pants steps into the light. Her short black hair, trim clothes, erect posture and efficient movements mark her as one used to dealing in official business. The audience applauds loudly. It is Sheela.

"Three years we have no crime in community," she says. "Then new friends come. Now there is fighting, stealing. This is shameful. This is shameful. I bring new friends to our home from the street, and you try to make our home a street.

"I try to show the world that the ones they call criminals can live beautifully with no crimes, and you bring shame on me with your fighting and stealing…

"Now I tell the big macho ones, the tough ones with their fighting and stealing. I tell you now to stand up and come up if you are so big and tough. Admit what you did. Show how tough you are." Dead silence. "Where are the big machos? You are so tough fighting but you cannot stand up? Where are you? Come forward with what you did." Dead silence.

A solitary figure rises. Heads turn. Applause breaks out. He is a sizable white man in his late 30s. He steps through the crowd and reaches the carpeted area. The shifting of the crowd settles as a technician hands him the mike. His words come out haltingly; he sounds Oklahoman and naive. "Well, I was over at the drive-by today…. After it was over…I was walkin' on the road and there was this trinket, I guess you'd call it…. It was layin' there on the road. I just picked it up. I figured if I didn't, somebody else would, you know? See, I collect trinkets and stuff like that. I have this hobby where I make things outta them. I use wire and stuff, and some of it comes out pretty good. I made some, like, balls and—"

Sheela's voice rolls over his: "We don't need hobbies now. Just tell the wrong thing you did."

"Well…I found this trinket over on the road. By the drive-by. It was just layin' there. It didn't look like anybody really wanted it—"

"Things don't just lay around in this community. They belong to people."

"Well. I brought it over here, and I had to go to the restroom, so I put it on the table right over there. But when I come out, it was gone."

"Just say you took the thing. You stole it. Say that."

He stares at the carpet, then looks blankly at the audience. He gives a nervous shrug and grins hollowly, his face a little red, like a grade schooler fidgeting before the principal. "That trinket was just layin' on the road," he says, "and I guess—see, I like trinkets—to collect 'em—"

"Just say what you did," Sheela urges. "Say that you stole it. Then we will return it to the person who owns it."

"I put it on the table over there. It's gone. I don't know—"

"Say you stole it and you can sit down."

He shakes his head, looking at the carpet, mouth open, trying to force something out. "Well…I…didn't think…. It was layin' there…. Maybe I should've brought it to lost-and-found."

"You stole it. Say that."

"I…well…. Maybe I did steal it. It didn't seem—"

"OK. This is your warning. No more stealing. You can go over there. Sagun [Sheela summons an aide], talk to him about returning the thing."

A white guy comes up to say he heard a black guy telling some other guys, "The Rajneeshees are kidnapping you. They got your clothes, and they're going to keep you here for three months to work like slaves." Then he points the black man out—a 200-pounder wearing a lavender cowboy hat and black leather jacket.

It happens that I sat next to this same black guy at lunch this afternoon. He was telling another man that he'd been out of Leavenworth prison a short time and didn't want to go back. He said he believed Rajneeshpuram was a good place and he wanted to stay. "I go back out there and I know I'll wind up behind them monkey bars again," he told his companion.

Now, he strides grinning to the front of the audience. Staring at the accuser, he reaches for the hand mike and says, "You think I'm afraid? You think I'm afraid to come up here?"

He turns to Sheela, towering over her. Two security men start toward him. "Would you not stand so close to me?" she says. He backs away. She demands an explanation for the kidnapping story.

"I was playin'," he says. He looks at the white guy: "I was just playin' with you."

She puts him on the next bus out.

A Look At Where Five of the Key People and Places in the Rajneesh Cult Saga Are Now

The Rajneeshees' Onetime Compound is Now a Christian Summer Camp. Here's What It's Like to Attend.

A Photo Gallery of the Rajneesh Commune Thirty Years Ago, And What the Land Looks Like Today