Real estate dealmaker Homer Williams is back at Portland City Hall, pushing another audacious plan.

Last year, Williams unsuccessfully championed a project to build a 1,400-bed homeless shelter on city-owned industrial property in Northwest Portland.

His ambitions for solving the city's homelessness problem have only grown since that setback.

During the past two months, Williams has described to Mayor Ted Wheeler and city commissioners a plan for building 12,000 to 14,000 units of affordable housing—more than 10 times the number to be built with the housing bond Portland voters approved last November.

"We need a big move in order to have any hope of controlling a problem that will grow out of control," says Williams. "I don't mean just chronic homelessness. I mean people who have worked all their lives."

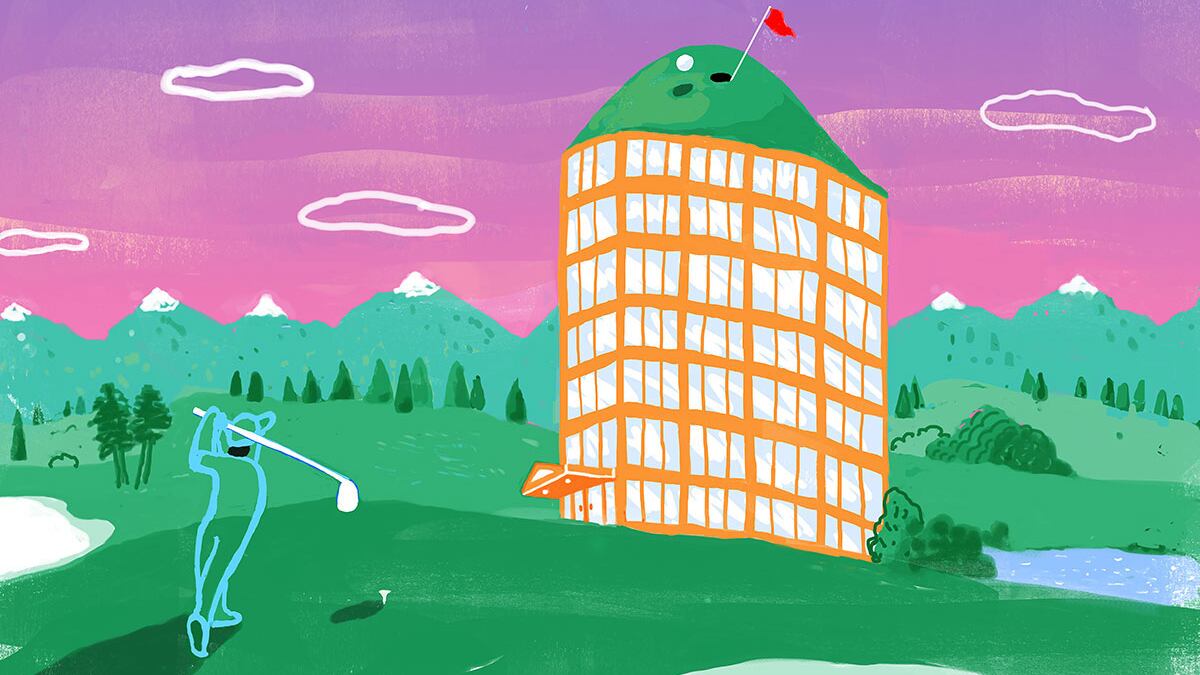

Related: Civic leaders say Portland should close its money-pit golf courses and turn them into apartments.

His plan is complicated, and hinges on changing the city's zoning designation of large properties.

The key is the privately owned 120-acre Broadmoor Golf Course in Cully. He wants the city to change the course's zoning designation from open space to industrial land.

State law requires the city to maintain a 20-year supply of industrial land. Converting the golf course to industrial use would add to the industrial land supply. That could allow the city to take other, closer-in properties now zoned industrial and convert them to residential use.

The process of rezoning land from open space to industrial, and from industrial to residential, creates wealth for landholders, because permission to develop a property increases its value.

A request to zone Broadmoor as industrial land may be filed within the next 30 days, says Williams.

Williams says a group of civic-minded Portland business leaders are working to buy the course within the next two months. The new owners would donate their property to a nonprofit, presumably collecting a tax write-off in the process. Williams would fundraise to buy industrial land but also use the increased value from rezonings to finance development costs.

Williams won't say where he hopes the city rezones industrial land as residential, in part because he doesn't want to push the values of those properties up.

But there are big swaths of industrial land along the Willamette River in Southeast and Northwest Portland—including the massive ESCO foundry shuttered last year—that would be highly attractive for residential development.

The deal faces significant hurdles. Environmentalists previously defeated an effort by the current owners to rezone Broadmoor as industrial land.

Some environmentalists object to developing golf courses because it reduces green spaces and wildlife habitat.

"Why do we need to destroy natural environment to do that?" asks conservation director Bob Sallinger of the Audubon Society of Portland.

He says the city should focus instead on getting an exception to the state requirement for an inventory of industrial land.

"Portland is going to be the first city to [get an exception] eventually," Sallinger adds. "We're out of room to expand. We're now in a choice: today, tomorrow or the next day."

And Williams' project conflicts with the comprehensive plan the City Council approved last year, laying out a long-term vision for where in the city land should be developed.

Despite the obstacles, nobody at City Hall is dismissing Williams' idea.

That's because of the enormous need for new housing and because of Williams' track record for pulling off developments previously considered impossible. He envisioned what became the Pearl District and the South Waterfront when both were barren, contaminated industrial areas. He developed the Forest Heights neighborhood on land considered unbuildable.

Williams also has a history of not building all the affordable housing he promised in other projects, as The Oregonian has chronicled. He says that won't be problem this time because his new project would include only affordable units, in four-story buildings for working people making 60 to 80 percent of median income.

Records show Williams has already pitched his land-swap concept to Mayor Wheeler and Commissioners Chloe Eudaly, Nick Fish and Dan Saltzman in the past two months. Wheeler, Eudaly and Saltzman's offices all tell WW the city leaders are intrigued by the idea.

"Dan believes in Homer's genuineness in helping to alleviate the problem," says Saltzman's chief of staff Brendan Finn. "He's seen his passion over the last year, year and a half."

The owners of the Broadmoor course are motivated, adds Wheeler spokesman Michael Cox. (Course manager Scott Krieger, who represented Broadmoor's owners at the meeting with the mayor, was unavailable for comment.)

Williams says the extraordinary challenges the city faces require bold thinking and action from City Hall.

"I've done three of the largest projects in the city," he says. "If they don't trust me by now, I don't know when they would."