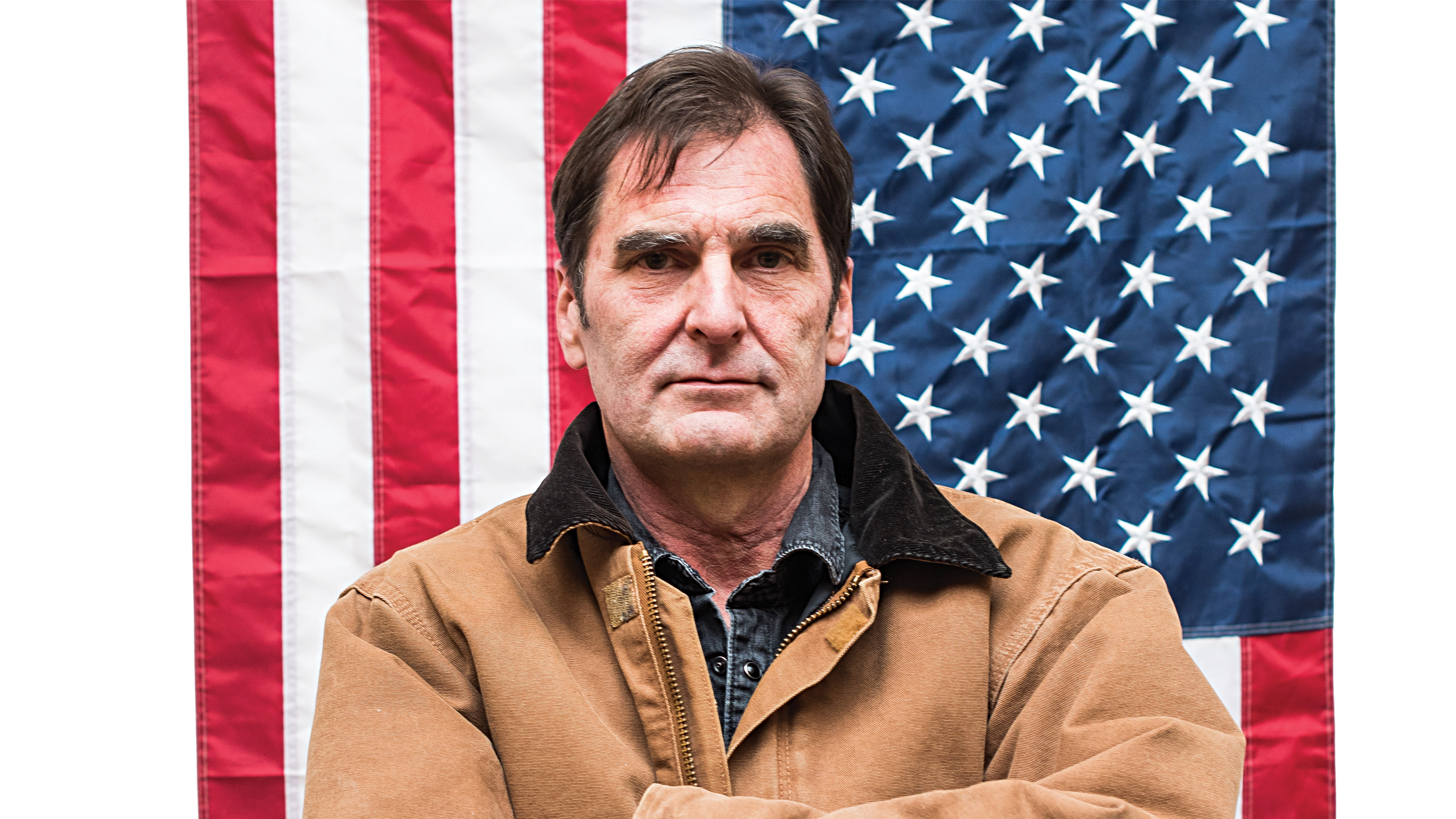

Ken Ward, the Oregon-based environmental activist who turned off an oil pipeline in Washington state last fall, argued in our Jan. 18 issue that his actions were necessary to defend the planet.

He will not be able to repeat that argument in his upcoming trial.

At a pre-trial hearing yesterday in Skagit County, Washington, a judge denied Ward's defense strategy, known as the necessity defense.

He informed WW by text last night: "They denied it," he wrote. "Looks like I'm in for 20 years."

The 60-year-old Corbett, Ore. man faces three felony charges and one misdemeanor for shutting off a valve on the Trans Mountain Pipeline in Burlington, Wash, which transports Canadian Tar Sands crude oil into the state for refinement.

Related: Ken Ward is willing to go to jail for the rest of his life to fight climate change. What about you?

Ward's action was a planned act of protest done in conjunction with other "valve turners" in other states. At the same time in Minnesota, North Dakota and Montana, fellow environmentalists turned off oil pipelines. They broke the law because they believed that the federal government gave them no other choice: by its inaction on climate change issues, they chose to cut off the flow of oil into the country.

But the complicated necessity defense that Ward planned to argue at next week's trial was shot down Tuesday.

His Eugene-based attorney, Lauren Regan, wasn't as pessimistic as Ward today: "I don't think it's a devastating blow," she said via phone.

"A necessity defense is generally an uphill battle," she says. "Courts are inclined to deny it. We knew going into it we had that."

The necessity defense, Regan says, wasn't Ward's only defense—just one of them. It would have allowed Ward to call expert witnesses, like environmentalist and journalist Bill McKibben, to testify on his behalf. That's off the table now.

"One of the defenses has been thrown off the side of the boat," Regan says. "We're still going to trial and it's still very much going to be a political trial."

Regan says that even if Ward is convicted of the charges — which carry up to 30 years of jail time — he likely won't be incarcerated. A guilty verdict would only trigger the beginning of a long appeals process, she says. And that's always been the plan.

"We knew this was a longer fight," she says. "We're going to move forward with this jury trial and put forward the best case we can."

Ward's trial is expected to begin Monday, Jan. 30, in Skagit County.