This story is a collaboration with Oregon Public Broadcasting. Roxy De La Torre contributed reporting and translation. Hear a radio version of the story here, or on opb.org.

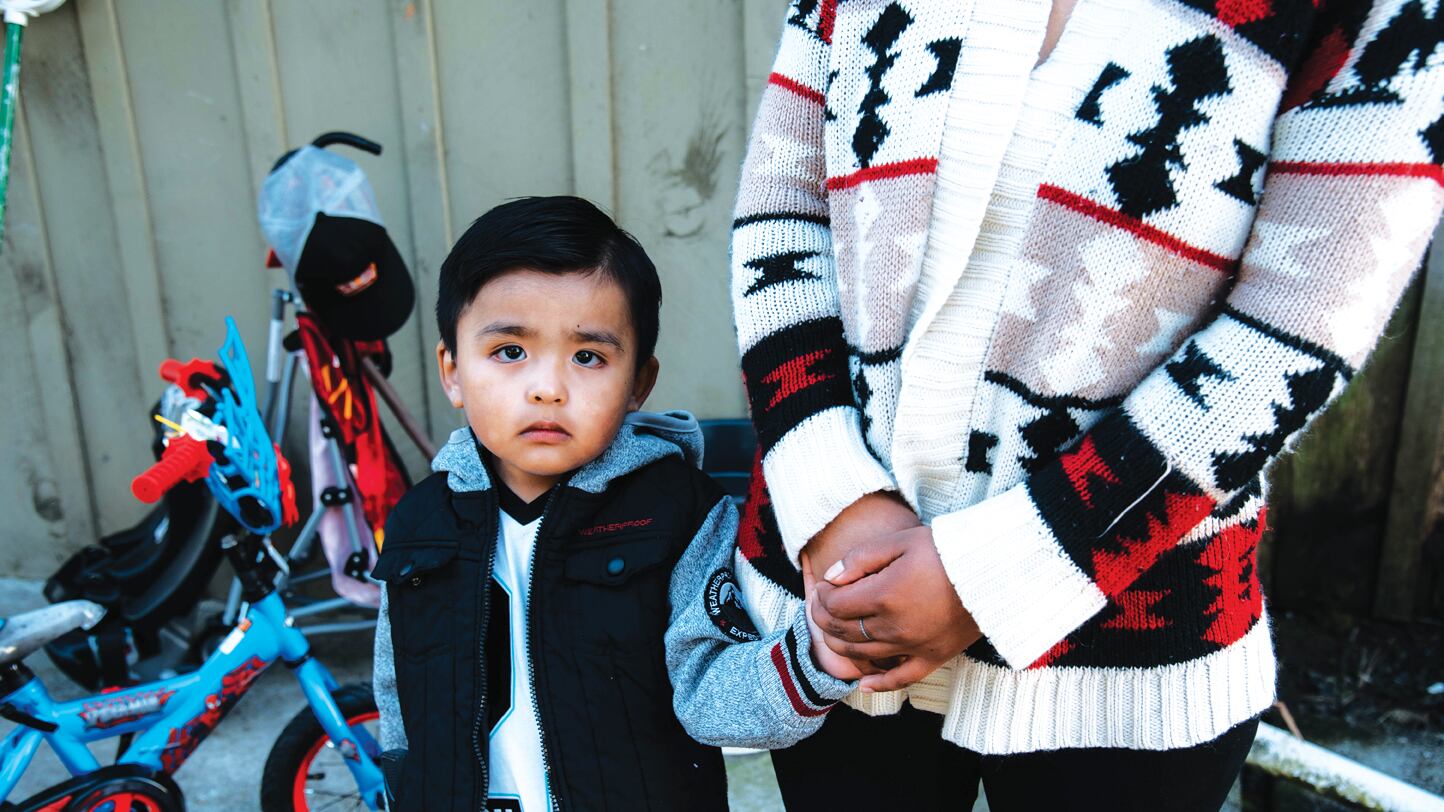

Brandon is in many ways a typical American 4-year-old.

His favorite food is chicken nuggets. He likes watching Power Rangers, singing "The Wheels on the Bus," and saying his ABCs. He goes to preschool in Silverton, roughly an hour's drive south of Portland.

For nearly a month, Brandon has been asking his mother, "Where is Daddy?"

For nearly a month, his mother has lied.

"He's working," she tells him.

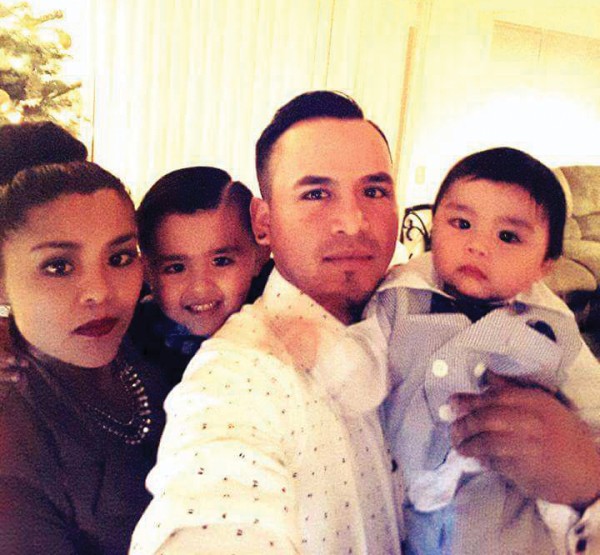

Brandon is a U.S. citizen, but born to parents who crossed the border from Mexico without papers.

Last month his father, Juan Carlos Andrade-Lopez, 26, pleaded guilty to driving under the influence of intoxicants in the wee hours of Jan. 22. After Andrade-Lopez spent a night in the Clackamas County Jail in Oregon City, he was arrested by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents.

They took him to a detention facility in Tacoma, Wash., where he has been ever since, awaiting a hearing that will likely order him to be deported to Mexico, a country he hasn't lived in for almost half his life.

The deportation will come with firm instructions not to return to the U.S. to see his son or the rest of his family—his partner, Araceli, or his other son, 1-year-old Oliver. (WW is not using Araceli's last name because she is undocumented.)

The remaining family now lives in an aging farmhouse in Central Oregon—a home filled with extended relatives, religious pictures and a growing sense of dread.

"Brandon started asking for his father after a week," Araceli says. "He cries for him every day."

Since Donald Trump became president, the federal government has launched a well-documented crackdown on illegal immigrants.

In less than two months this year, ICE agents arrested 578 undocumented workers in Alaska, Washington and Oregon—a 200 percent increase from the same period last year.

Deportation is aimed at punishing people who crossed the border illegally, but it often means breaking up families and leaving children born in the U.S. without one parent, or both of them.

"U.S. citizen children are really at the whim of what happens to their parents," says immigration lawyer Anna Ciesielski of private law firm Oregon Immigration Group.

Related: Why is an Oregon county jail holding immigrant detainees in a sanctuary state?

The issue of children born in the U.S. to undocumented parents has long been a hot button in the immigration debate.

More than 3.5 million undocumented immigrants in the United States have children who are U.S. citizens, according to a 2014 analysis by the Pew Research Center. In Oregon, Pew figures from 2014 suggest at least 40,000 U.S. citizens probably have parents who could be deported.

The story of the family left behind in Silverton when Andrade-Lopez was arrested is a story playing out across the nation.

"He's missing his dad a lot, a lot, a lot," Araceli says of Brandon as she sits on a comfy brown couch, crying softly. "They were never separated before—we were never separated—for more than a week."

Andrade-Lopez and Araceli met in 2011, set up on a date by mutual friends. They had a couple things in common. They both worked on farms. And they had crossed the U.S. border as teenagers.

Andrade-Lopez arrived in Oregon in 2006 at age 15, crossing into the U.S. from the Mexican state of Michoacán with his parents and brother. He went straight to work tending grapes.

Araceli arrived from a small town outside the Mexican city of Puebla in 2010 at age 19 to join her mother and brother, who were already in Oregon. Araceli came to the U.S. by walking for two weeks across the Southwestern desert with the help of smugglers. She left behind a 7-year-old sister, who she'd been caring for since their mother left for the U.S.

"I didn't want to think I only had that life," says Araceli, speaking in Spanish. "There weren't many opportunities."

In Oregon, she started picking chilies. Araceli later tended grapes, and she canned fruit.

Araceli and Andrade-Lopez met here a year later. It was winter, and she was out of work because farms weren't hiring. He was landscaping Portland yards.

Araceli remembers thinking Andrade-Lopez was funny; he also was very attentive. They never got married, but two years later, in 2013, they had their first child: Brandon. Their second son, Oliver, was born last year.

Before his arrest, Andrade-Lopez, who also has a 7-year-old daughter from a previous relationship, was a playful father who liked to kick a soccer ball with Brandon or get down on all fours to buck Brandon off his back like a bull. The family shared a two-bedroom apartment in Silverton.

Araceli describes the two as inseparable.

"His dad was everything for him," she says. "If his dad went to the store, he wanted to go to the store with him."

But Andrade-Lopez was arrested twice within the past year for driving under the influence of intoxicants. In September, he pleaded guilty to DUII and driving with a suspended license, but the case was diverted, meaning he had to go through a court-ordered program. He did not have a criminal conviction from that case. Then he drank and drove again Jan. 22.

Rose Richeson, an ICE spokeswoman, says federal agents arrested Andrade-Lopez after his two DUIIs. He was already in the federal immigration system, probably because of a speeding ticket in 2012. The drunken-driving arrests violated the terms of his release, Richeson says.

"Mr. Andrade remains in ICE custody at the Northwest Detention Center pending resolution of his removal proceeding," she says.

DUII is an offense the Obama administration also made a priority for deportation. Nothing short of a complete rethinking of immigration policy is likely to save families like Andrade-Lopez's from an agonizing decision whether to pull up roots and return to Mexico.

For many lawmakers, Andrade-Lopez's decisions—first to enter the U.S. illegally, then to drive while drunk—are good reasons to kick him out of the country.

"As soon as you go cross the border, you break the law," says Rep. Sal Esquivel (R-Medford). "It's more unfortunate that the kids get involved. But it's the parents who make it hard on their kids."

Araceli says she realizes how her partner's choices have wrecked her family.

"He was irresponsible," she says. "We all know that's really bad. I cannot tell you why he was driving with alcohol. He made a mistake. He knows it's no good. He did it, and now we're in this situation."

Yet Araceli never expected this outcome. The family had made no preparations.

The family Andrade-Lopez left behind now lives in a farmhouse filled with extended family. Brandon, Oliver and Araceli share one of three bedrooms.

The house is tidy—visitors leave their shoes at the door. A safe distance from a wood stove, Brandon has a plastic play kitchen. A corner table holds a painting of Jesus and a Virgin Mary figurine.

When Brandon wants to talk to his father, he asks for his mom's phone and tries calling him through Facebook Messenger.

"He doesn't answer," Araceli says. "[Brandon] says, 'Ooh, he's working, but I want to see him.' So he starts going through photos of his daddy on my iPhone."

Andrade-Lopez does call every night from detention, but the phone conversations are confusing for Brandon. He expects to see his father when they talk. But the detention center's phones don't have cameras. Araceli tells Brandon the camera on his father's phone is broken.

In the evening, about the time his dad would usually return home, Brandon gets hopeful.

"He looks through the window when he sees a car that is coming," Araceli says. "[When he hears a car], he screams, 'My daddy!' He sees it's not his dad, and he gets sad."

His father's ICE arrest has meant big changes for Brandon.

Araceli has gone back to work, pulling 11- or 12-hour shifts in the hops fields, just as Andrade-Lopez used to, earning $11.50 an hour. In the summer, the job will require working seven days a week.

At 5:30 on a recent Tuesday morning, she got up and fixed lunch for her kids before heading out to the fields to hang wires that allow the hops plants to grow tall without flopping over.

When she's not working on hops, she helps tend grapevines on the ranch. She doesn't return until nearly 7 pm and sees her sons only briefly before bed.

Brandon now stays with a baby sitter, or his uncle drives him to his Head Start preschool in Silverton.

"He's not the same as he was before," Araceli says.

He has started wetting the bed at night and peeing his pants during the day. His mother has put him back in diapers.

Brandon's story is like those of many across the state—and fears of a similar fate have spread wider.

Oregon has an estimated 130,000 undocumented immigrants, according to the Pew Research Center numbers released last year. That's 3 percent of the state's population and more than 30 percent of Oregon's immigrant population.

More than 70 percent of the state's undocumented immigrants are from Mexico. Half of them have lived here since at least the early 2000s.

For these families, the immigration crackdown feels like a ticking clock.

"My father told us we need to start preparing," says an 18-year-old senior at Northeast Portland's Benson High School. He is a U.S. citizen whose parents are not, and he asked that his name not be used.

A couple weeks ago, his dad, who works in the laundry room of a Portland hotel, got worried he'd be picked up by ICE after a report of federal agents downtown.

"It's like he told us we have to be prepared for his death; it's just sooner," says the senior, who has two younger brothers and expects to stay in the U.S.

At Century High School in Hillsboro, the fear of ICE arrests means undocumented parents are no longer willing to drive to pick students up, says Luis Nava, adviser to the after-school Latino Union Club.

Instead, students are riding the bus home at the end of the day and not showing up at club meetings.

Standard attendance at the Latino Union Club used to be 25 or 30 kids. Last month, it fell to zero, says Nava.

American kids now contemplate an impossible choice—to follow their deported parents to Mexico or stay in their birth country as de facto orphans.

"I was worried," says Edgar, 16, a junior at Centennial High School. He is an American citizen, but he never considered the idea that he would stay in the U.S. without his parents. "They're our parents. There's no one who could love us as much as them."

Catherine, 14, a Portland eighth-grader at Cesar Chavez School in North Portland, says when her estranged father was deported last year for dealing drugs, it didn't matter to her because they'd never been close.

But ever since the Trump administration began its crackdown, she worries. Her mother and stepfather have resident status, so there's little danger she'll lose another parent. But in a sign of the fear that has gripped Latino communities, Catherine questions whether she would follow her family back across the border.

"I consider myself full-on Mexican, even though I was born here," she says.

But still, she thinks she would stay in the U.S. if her mother and stepfather had to leave.

"The whole reason of why my mom came to the United States is to give me a better life," Catherine says.

Kids like Brandon have little recourse.

Once deportation proceedings begin, it's possible to halt them due to "extreme and unusual hardship" to the children.

But a child's inability to speak a foreign language or a lack of cultural connection to the parents' home country is not considered unusual enough, lawyers say, to win over an immigration judge.

Successful appeals usually involve children with serious medical problems or special needs. And there is a cap on how many hardship waivers may be handed out. There's a two-year backlog at this point, says lawyer John Marandas, who is one of the Oregon immigration attorneys' liaisons to ICE.

Any relief for American kids with undocumented parents is not likely to arrive soon.

In 2014, after Congress failed to take up immigration reform, the Obama administration announced a program to allow parents to stay in the United States, even without obtaining permanent legal residence.

But Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents, or DAPA, was halted by the courts. The legal battle over a judge's injunction in United States v. Texas went to the U.S. Supreme Court.

That injunction has now expired. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is now free to draft a policy to protect parents.

But it's hard to imagine the Trump administration taking that up.

"Given the current political climate, it's unlikely the administration would create such a program," says Shiu-Ming Cheer, senior staff attorney and field coordinator at the National Immigration Law Center.

In the face of a father's deportation, the choice for Araceli might seem obvious: She and her two children could reunite with Andrade-Lopez in Mexico. But it's not so simple. Both Araceli's mother and Andrade-Lopez's parents are here. So too are some of her siblings and his.

Her family and Andrade-Lopez's came here because they wanted a better life.

"We all know that working here you can do many things," she says. "Working—and working hard—you can buy things for your kids. You can send them to school. You can go out and have fun with them.

"In Mexico, no, because even if you work and work and work, it's not going to be the same as here."

She starts thinking about Brandon and 1-year-old Oliver, who is sitting on her lap yawning in striped pajamas.

"He can have stuff, clothing, not wealth but his toys. He can go to the playground," she says. "In Mexico, I never had that."

She wants Brandon and his brother to grow up and get jobs as professionals. She imagines Brandon becoming a police officer or a lawyer.

But Araceli doesn't know how she can give him that life now. Andrade-Lopez's choices and decades of U.S. border policy have left her with an impossible decision—and her kids with a future in limbo.

She has no promise to offer her children that is both hopeful and true.

"Brandon asks for his daddy twice a day," Araceli says, "and I just tell him, 'Soon.'"

This story is a collaboration with Oregon Public Broadcasting. Roxy De La Torre contributed reporting and translation. Hear a radio version of the story on opb.org.

Immigrant Parents Without Papers Prepare for Leaving Their Kids Behind

On a recent Wednesday night, Alice Perry, an advocate with the Portland nonprofit the Latino Network, was at a meeting for undocumented students at Chemeketa Community College in Salem. Perry and others from the group have been crisscrossing the state to help undocumented parents prepare for arrest by Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

"We started hearing from families that there was a lot of fear after the election, and there was concern, principally about what would happen to their children should they be detained or deported," Perry explains, before launching into the practical advice.

The to-do list includes items that would be useful to any parents who want to be prepared for an emergency or their own death: a list of contact information for doctors, schools and family members.

There's a power-of-attorney form, designating who will take care of the children.

That last question is complicated in undocumented communities, because while ICE will recognize a power-of-attorney form presented upon arrest, the agency may also scrutinize the immigration status of any caregiver left in charge of the children, meaning the family often has to find someone outside its social circle to care for a child.

Another thing Perry advises is obtaining official documents for kids to travel—U.S. passports or documentation from the parents' home country, so kids can be ready to leave the U.S. if they're following their parents.

Some parents have been doing just that.

In the past four months, the consulate reports issuing 810 requests for Mexican birth certificates—a key document needed for establishing dual citizenship, according to an official tally. That's more than double the number from all of last year, when 314 such requests were issued.

That's a measure of how many people are trying to make sure their U.S. citizen children can join them in their home country if they are deported.

Children of Mexican immigrants are welcome in their parents' home country. It's a matter of filling out the paperwork correctly.

On a Thursday afternoon at the Mexican Consulate, Agusto Ortega Perez, 50, comes to get a passport before his next ICE appearance—as part of demonstrating that he could and would leave the country if ICE decided to reject his case for staying.

Ortega Perez is crowded in among the families waiting their turn. But in under an hour, he is fingerprinted and pays $136 cash for a passport valid for 10 years.

The consulate offers him a form for getting his kids documents for moving legally to Mexico.

"It's like visiting an American embassy abroad in wartime," says his attorney, Maria Zlateva. "They're trying to help."