No story dominated Oregon news in 2016 quite like the occupation of Malheur National Wildlife Refuge by Ammon Bundy and his anti-government militants.

A new lawsuit shows that another battle over federal control of land and animals in Eastern Oregon is heating up.

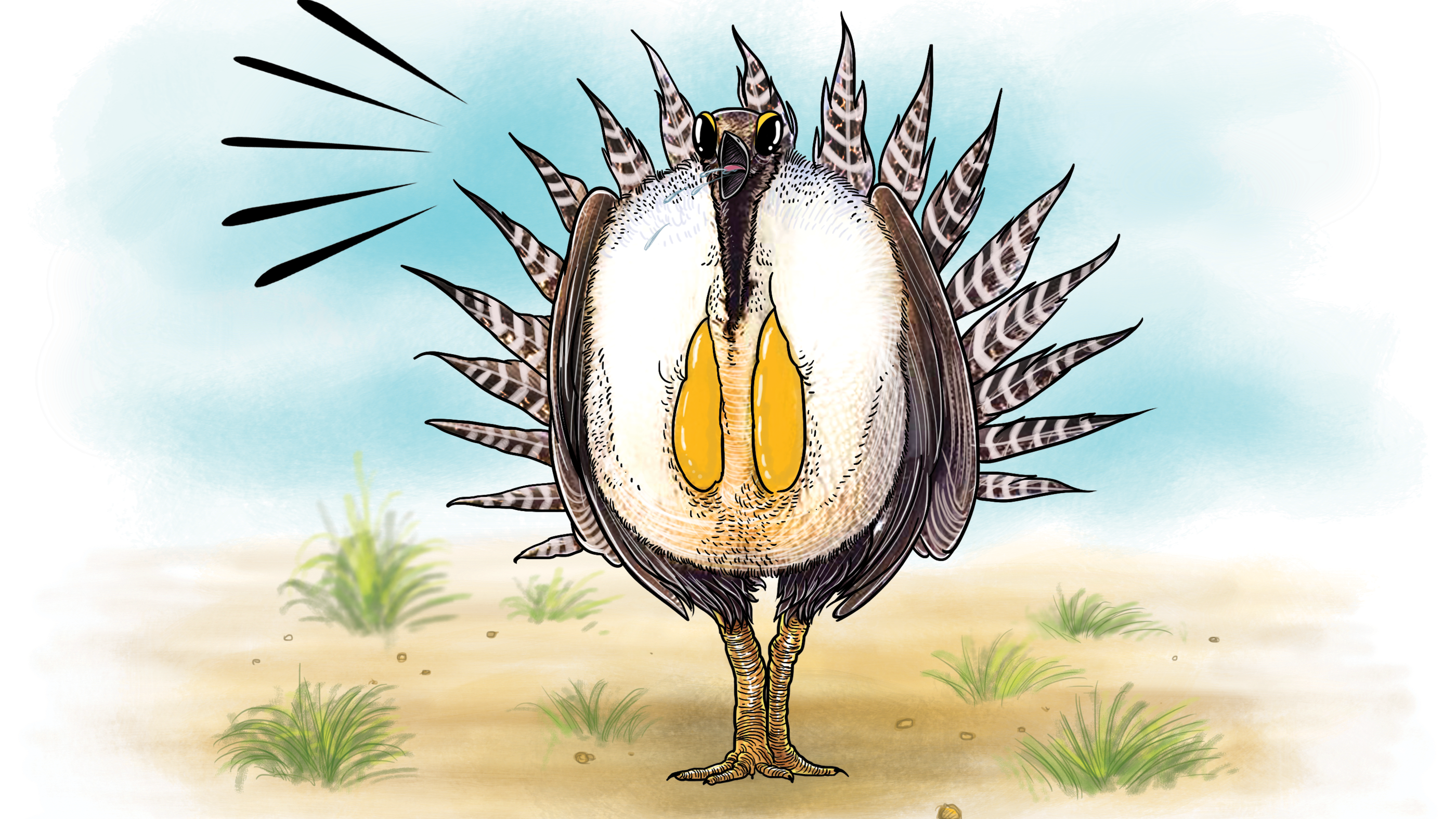

The subject? The greater sage grouse—a flamboyant bird that's the size of a chicken but packs the attitude of a samba dancer.

For five years, federal and state officials have been hammering out a deal to save the sage grouse across 11 Western states, while avoiding the more drastic measure of placing it on the Endangered Species List. A compromise reached in 2015 was touted from Salem to Washington, D.C., as a model for getting cattle ranchers to work with the government and conserve wildlife.

But 2017 is the year when Oregon ranchers must actually put that plan—called the Greater Sage Grouse Conservation Strategy—into practice, using more than $9 million in federal funds to clear pastures of hazards that can kill the birds.

And the lawsuit, filed Dec. 7 in federal court by a local government agency that works with ranchers in Oregon's rural Harney County, shows the agreement is fracturing before it gets started.

For the first time, a local government agency in Oregon—one that's supposed to manage a part of the grouse strategy—is threatening to back out.

The reason? Requirements to keep cows away from sage grouse mating sites on public lands in the spring and to keep grass at least 7 inches high on public pastures. Ranchers say those rules could push them out of business.

Such squabbles a five-hour drive east of Portland may seem a world away. But the Bundy invasion showed how a distant disagreement over the management of federal lands can be exploited by outsiders with their own agendas.

Related: How Ammon Bundy created a fantasy camp for commandos in Eastern Oregon.

The sage grouse is a symbol of the wide open spaces that attract many newcomers to this state.

Like salmon and spotted owls, the grouse finds itself at the center of the state's urban-rural divide, pitting ranchers who want to make a living off of federal lands against environmentalists—many of them city dwellers who want to preserve the vast federal lands that constitute 53 percent of the state.

The underlying question is the same as in the Malheur occupation: Who should benefit from those lands—the people who happen to live near them, or everyone?

"This doesn't have to be Oregon's next major land-use fight," says Bob Sallinger, conservation director for the Audubon Society of Portland. "But it is the test of the collaborative process. It's easy to sing 'Kumbaya' when signing documents, but more difficult to work through challenging issues."

Ranchers who want the deal to succeed are also worried—fearing if the bargain fails, what comes next could cripple them.

"It has the potential to be real serious," says John O'Keeffe, president of the Oregon Cattlemen's Association. "We're all losing sleep over this."

The sprawling rangelands of Eastern Oregon, where sagebrush sprinkles the desert like Christmas tinsel, are home to two iconic sights: grazing cattle and the mating dance of the greater sage grouse.

The grouse, which attracts a mate with a swaggering display that brings to mind Popeye impersonating a peacock, has had its habitat decimated by cattle—which chew native bunchgrasses down to the dirt, clearing the ground for invasive annual grasses that fuel devastating wildfires and choke out the tender, leafy plants that sage grouse chicks depend on.

Ranchers have modified their grazing practices. But by 2010, sage grouse were in such decline that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced it would list the bird as "threatened" on the Endangered Species List. That distinction would empower the government to ban killing the bird, even by accident.

That ban would be tough for ranching operations, where the low-flying birds impale themselves on fences, drown in water troughs and are vulnerable to predators attracted by cattle herds.

The 2010 warning of an Endangered Species Act listing spurred ranchers across the West to work with the government.

Oregon ranchers agreed to match government funds with their own money and sign agreements to flag fences for the bird, remove the juniper trees where their predators perch and add little ramps to water troughs so the birds don't drown. (Much of this work in done on private property, not just public lands—the birds regularly cross between them.)

It seemed to have worked. In 2015, U.S. Fish and Wildlife announced there were already enough solutions in play that the bird didn't need to be listed. Last March, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell visited Burns, Ore., to praise the compromise: the Greater Sage Grouse Conservation Strategy.

"There's a real opportunity to showcase the good things about what happened here as a real model for cooperation that could be brought across the American West," Jewell said.

In 2017, even more money will start flowing into the plan: The U.S. Department of Agriculture gave Oregon a $9 million grant to be used over five years and matched by private landowners.

"The [grant] funding was the first big shot of money," says Gary Miller, field supervisor for U.S. Fish and Wildlife. "There hasn't until now been this huge pot of money to help folks get things going on the ground."

But on Dec. 7, the Harney Soil and Water Conservation District sued Jewell, the Department of the Interior and the Bureau of Land Management in federal court in Washington, D.C.

The agency that filed the suit is the primary vehicle to funnel federal dollars to ranchers who agree to make improvements that will help the sage grouse.

In the lawsuit, Harney Soil and Water Conservation objects to requirements to keep cows off grouse breeding grounds in the spring, and to keep grass 7 inches high.

The suit claims the government is managing the land strictly for sage grouse recovery without considering the impact on ranchers. And that's illegal, the lawsuit says, because the government is required to manage the land for "multiple uses"—including human ones like ranching and recreation.

This isn't the first time a local government agency has sued the feds over the sage grouse: Several counties in Nevada filed suit as soon as the federal plan was announced in 2015.

But it is the first such lawsuit in Oregon, and its timing has set off warning bells for government officials: Local ranchers have talked about accepting stricter rules, but aren't willing to follow through.

Erin Maupin, a Harney County rancher, says the lawsuit was necessary because the rules would be disastrous for ranchers. Spring is a crucial time for cattle to graze on public land, Maupin says.

"That's when we're growing a hay crop," Maupin says. "We can't turn our cows out on [private] meadows then because then we'd have nothing to feed them in winter. If this was long term, it would be the end of family ranching in the West."

The lawsuit places new pressure on federal and state agencies that are already nervous about provoking backlash.

Ammon Bundy and more than a dozen other anti-government militants still face federal trials this year for armed standoffs with the feds. The political aftershocks of the Malheur occupation left President Barack Obama unwilling to seek additional federal protections for the Eastern Oregon wilderness of Owyhee Canyonlands.

Gov. Kate Brown is no bolder.

"At this point, we're not considering any regulatory actions," says Brown spokesman Bryan Hockaday.

Related: "Oregon's Grand Canyon" was going to be a national monument. The Bundys killed it.

And the Harney lawsuit arrives even as new figures show grouse populations are rapidly declining in their northernmost habitat in Oregon.

Grouse numbers around Baker County, Ore., have dropped by 76 percent in the past 13 years, according to Lee Foster, sage grouse conservation coordinator for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Environmentalists say the drop is because federal officials are afraid to crack down on grazing, ATVs and other human activity in grouse habitat. (Federal and state wildlife managers blame ravens preying on grouse eggs and chicks.)

By 2020, wildlife managers will have to prove to their federal counterparts at U.S. Fish and Wildlife that the strategy stopped the bird's decline enough to keep it off the Endangered Species List.

Sallinger says the next moves by state and federal officials will reveal whether the government has the will and muscle to protect the sage grouse.

"The problem is relatively obvious: This population is declining down to nonexistence," Sallinger says. "But does the government have the teeth and the buy-in that will result in a real solution?"