A research team at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland has become the first American scientists to successfully edit the genes of human embryos, Technology Review first reported today.

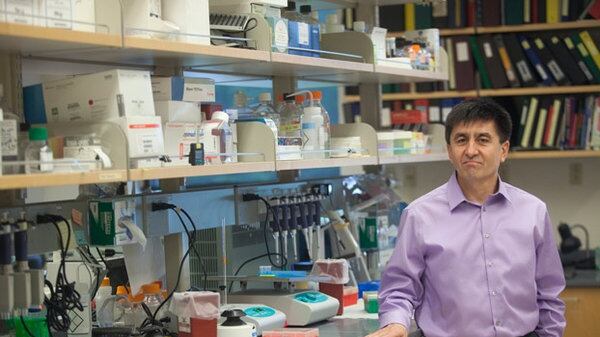

The implications of the effort to alter genes pre-birth—a study spearheaded by OHSU researcher Shoukhrat Mitalipov—could mean a cure for genetically inherited diseases.

The embryos tested were only allowed to develop for a few days, and none were ever intended to see a womb, but the work is still ethically controversial. Some critics have warned it opens a Pandora's box of genetic engineering.

Mitalipov and his team will be the first to prove that it is possible and safe to correct defective genes (ones that carry inherited diseases) in embryos, thanks to sperm donated by men who carried genetically inherited diseases.

Worldwide, this isn't the first attempt at embryonic genetic modification—three other studies have come out of China. But this may be the most robust study to date in terms of the number of embryos tested.

Reportedly, the technique Mitalipov and his team used is called CRISPR, which allows geneticists to edit single strands of DNA. It's a technique that's received plenty of scrutiny for fear of the creation of genetically enhanced, or "designer babies."

Just last year the U.S. intelligence community deemed CRISPR a possible "weapon of mass destruction." (The fear, in short, is that an unscrupulous government could deploy genetic engineering to create soldiers immune to chemical weapons—then deploy those weapons in a war.)

In February, the US National Academy of Sciences put out a report that drew the ethical line at genetic enhancements (i.e. higher intelligence), but green-lighted making gene-edited babies with the intention to eradicate certain diseases.

Mitalipov declined to comment to Technology Review, citing that the report is still pending publication. But in a 2014 WW cover story about groundbreaking work that Mitalopov did on blending DNA, in order to treat mitochondrial diseases, the geneticist made clear his view on ethics critics.

"In terms of ethics, we always ask the wrong people to tell their ethical grounds, like professional or religious ethicists," he said. "I think it's most ethical if you ask the patients or families themselves, and I think those should be the deciding voice in whether we should proceed or not."

Other scientifically controversial work of Mitalipov's include the first successful cloning of monkeys in 2007 and the growth of human stem cells through cloning in 2013.

Though this most recent study has yet to be released, other scientists who were involved in the project did verify its nearly unprecedented nature with Technology Review.

"So far as I know this will be the first study reported in the U.S.," said Jun Wu, who is involved with the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, and who also helped with OHSU's genetic modification of embryos via CRISPR.

U.S. law still blocks turning a gene-edited embryo into a baby.