Deep in the Columbia River Gorge is a parking lot that never freezes. Not a single snowflake sticks.

The source of this artificial summer in The Dalles, a town of 13,000 people 85 miles east of Portland where February temperatures can dip to 16 degrees, is a nearby warehouse, a cream and green concrete building with no windows and no signs.

The reason for this banana belt? Air pumped from exhaust vents in the warehouse bathe the parking lot with a warm sauna-like breeze—heat coming from the 2,750 computers that hum inside.

You read that right. Two thousand, seven hundred fifty computers, each the size of a shoe box.

This is Terrence Thurber's cryptocurrency mine.

Thurber, a boyish, 33-year-old college dropout with a pompadour of blond hair, a perpetual five o' clock shadow and a gambling habit that sent him jetting off to Vegas this week, moved to The Dalles from Costa Rica three years ago. He once hawked diet pills online. Now, he is mining for Bitcoins.

"This is the future," Thurber says. "The sooner people get on board, the better off they'll be. It's a 'shoulda, coulda, woulda' situation."

Cryptocurrency is the talk of the tech and financial world. The most popular cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, has made paper billionaires of some, as speculators drive the value of each coin up and down. But mostly up—Bitcoin increased in value more than 1,100 percent last year.

All told, there is more than $168 billion in Bitcoins around the globe, and it's just one of hundreds of cryptocurrencies. Bitcoin is being used to buy cars and houses, and book first-class flights (as well as for darker purchases, like opioids and guns).

Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz says the speculative frenzy is a sham, and warns that eventually the cryptocurrency craze will be viewed as another tulip fever, when irrational enthusiasm for flower bulbs crashed the 17th-century Dutch economy.

But for the moment, miners like Thurber are gripped in a mania, using thousands of shoebox-sized computers to solve the complex math problems that produce cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. That effort uses extraordinary amounts of computing power and electricity to run a highly sophisticated algorithm—last year, Bitcoin miners consumed as much power in one year as the nation of Portugal did in the same period.

Thurber says he moved to The Dalles for one reason only: cheap hydroelectric power. It costs 3 to 4 cents per kilowatt-hour, less than half the U.S. average.

Thurber's mine constantly draws three megawatts of power per hour. That's enough electricity to power a town the size of Sisters.

And Thurber says his 15-employee company, called OregonMines, is now the third-largest consumer of electricity in The Dalles. His monthly power bill is $75,000.

While Thurber's OregonMines is the only industrial-sized cryptocurrency mining operation in The Dalles, and one of fewer than a dozen in Oregon, more are coming.

"We may well become the center of cryptomining in the world," says Robert McCullough, an energy consultant who once set power rates at Portland General Electric. "We may find our burgeoning surplus of energy will make us quite a capital for useless servers solving useless puzzles. It's not as if we have a huge amount of employment attached. It's not as if you're going to have a big staff and a lot of smart people working on it."

The Bitcoin boom poses a challenge to small towns like The Dalles. Electricity here may be cheap, but it isn't endless. Dams kill endangered salmon. And the more hydropower is used by Bitcoin miners, the more the rest of the state must rely on electricity generated by fossil fuels, including coal.

"I wouldn't blame a [utility] for being skeptical," Thurber says. "Cryptocurrency would gobble up as much power as it could, if we didn't have a bunch of measures in place that are holding us back."

It is difficult to say whether Bitcoins have made Thurber rich.

He and his father, Tom Thurber—his business partner—won't discuss their revenue. Terrence Thurber says he has mined thousands of Bitcoins but won't disclose an exact figure.

They do claim that OregonMines is in the black. Given that the company's expenses total at least $2 million a year, that means Thurber is running one of the largest companies in The Dalles. (Oregon Business magazine first reported on Thurber's mine earlier this month.)

What is clear is that Terrence Thurber is a gambler.

He actually purchased his first Bitcoin while playing online poker tournaments in Costa Rica.

It was 2012, and Thurber was working for a company that created web ads for diet pills.

Thurber grew up in suburban Connecticut tinkering with computers and playing video games. By 27, he was a globe-trotting online salesman.

In the nine years since he dropped out of the University of Connecticut, the diet-pill marketing job took him around the world—first to Manila in the Philippines and then to Central America. He married and divorced—leaving his family, including two young daughters, back in the States. Settling in Escazú, Costa Rica, he bought two pit bulls named Mia and Q from a friend there.

His 67-year-old father and business partner, Tom, says Thurber was always impatient and eager for risk—qualities that fueled his gambling hobby and his business ventures.

"His games are poker and blackjack, which are, as you probably know, the two games of some skill," Tom Thurber says. "I think that's what attracts him."

One day, a Bitcoin ad that popped up on his computer caught his attention.

He decided to poke around. He bought and traded a few coins, each worth just dollars at the time.

"I had 10-timesed my money by the end of the night," he claims. "At that point, I had effectively taken the red pill. Any caution, any heed was just out the window."

He had always been chasing money. Now, he could literally manufacture it.

But creating Bitcoin wasn't as easy as trading it. He began by going on a shopping spree. "I went online and found every piece of that hardware that I could and I bought it," he says, "until I couldn't find any more hardware."

Thurber bought four ready-made specialized computers—and when he couldn't find more, he started buying the chips he needed to build his own. He first plugged the machines into a space he shared with a Chinese car-part manufacturer in the Shenzhen province of China. After two months, he moved the computers to a designated cryptomine further inland.

For eight months, his computers hummed in China while he enjoyed Costa Rica. But the restrictions of renting space in someone else's warehouse, in another country with increasing internet regulations, began to weigh on Thurber.

Bitcoin miners are an odd bunch. Most of them are men, and they are motivated not just by money but by a libertarian philosophy—a desire to be free from government intrusion.

Thurber is no exception. "It's hard to put a quantity value on freedom," he says. "Cryptocurrencies will liberate your personal money flow."

He needed a new mining spot. He picked Oregon.

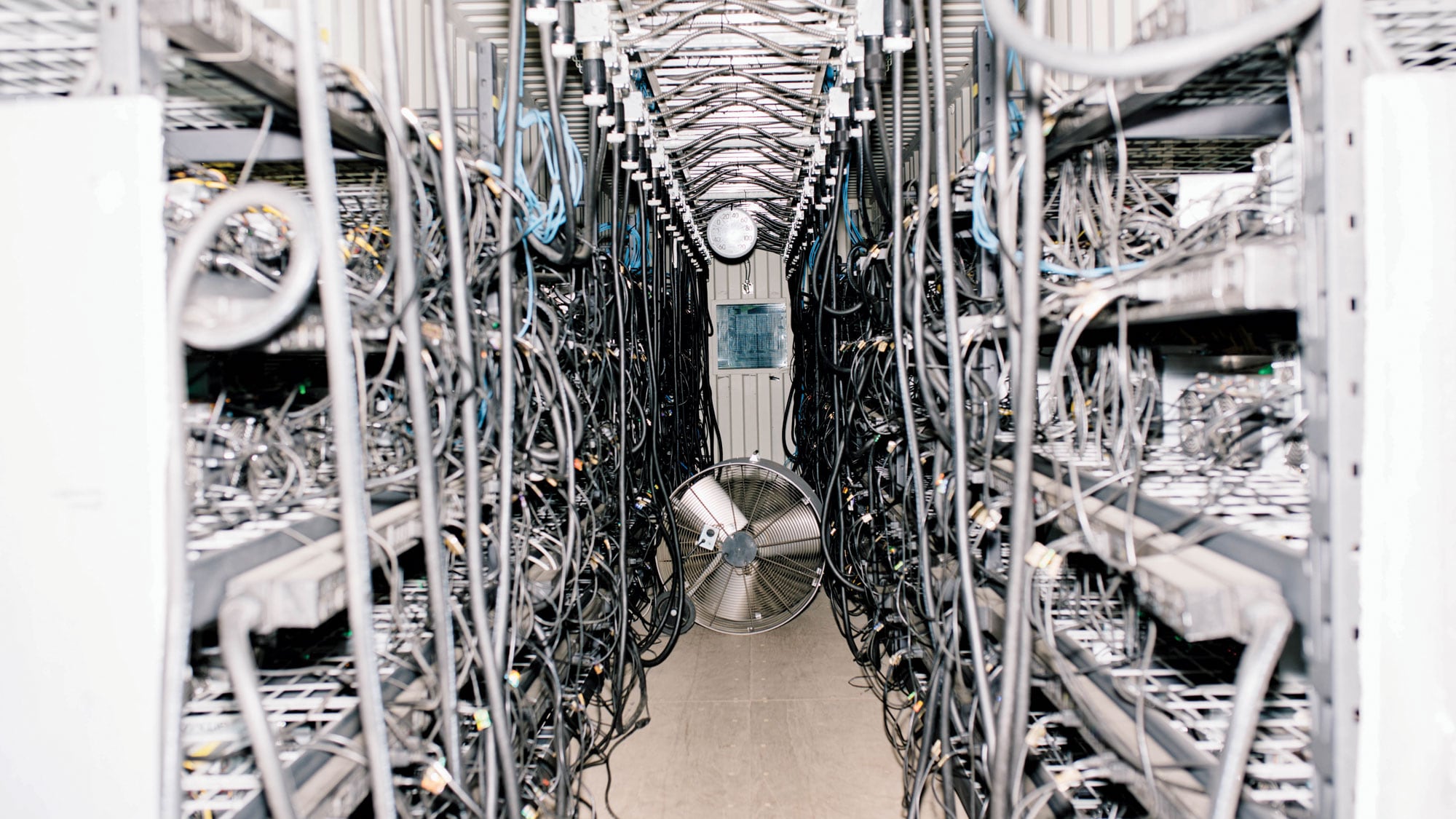

Inside the headquarters of OregonMines, it sounds like riding in a convertible flying down the freeway.

That's the sound of 2,750 computer fans spinning ceaselessly to keep the machines cool. Four-foot-high industrial fans whir even louder to keep fresh air flowing over the equipment.

Thousands of computers called AntMiners, each no larger than a loaf of bread and looking a lot like 8-track tape players, are stacked in room-length cabinets that create hallways in the cavernous warehouse. The machines cost Thurber well over $5 million.

The AntMiner computers require immense amounts of electricity to solve complicated puzzles. Thurber says The Dalles is the perfect place for a Bitcoin mine.

"This location is really special," he says. "It's close to a major metro. It's got good weather patterns. When it's hot, it's dry, which is good for our cooling systems. And, of course, the power is reasonable out here."

Thurber says he was looking for affordable, reliable power—which meant setting up shop somewhere that wasn't already inundated with Bitcoin mines. Experts estimate tens of thousands of Bitcoin mines are operating worldwide, but no one knows for sure.

The Dalles had plenty of available power. (Its big customers were a Google data center and one aluminum processing plant.) And it was closer to interstate freeways and a major airport than the rural Washington counties where power was even cheaper.

Thurber packed up his belongings, put the pit bulls on a plane, and arrived in The Dalles in February 2014. He hired his father, who was buying property for Mrs. Fields cookie franchises, to oversee the construction project. He bankrolled the operation with money he made mining Bitcoins in China and from selling ads for diet pills.

Thurber says he invested $6 million in the business before he switched the computers on. That would require mining 600 Bitcoins to make up the cost.

But he actually makes the bulk of his regular income from dozens of other miners who rent space in OregonMines to run their own AntMiners. Thurber also pulls in cash from transaction fees paid by Bitcoin users when they buy or sell something using the cryptocurrency—think of it as a bank fee that adds up with each transaction. The fees can ultimately be worth thousands of dollars to Bitcoin miners.

He has 15 employees, 11 of them working full-time jobs engineering, programming and repairing the computers.

"The Dalles was not exactly popping with activity when I got there," Thurber says. "My jobs are all new jobs with new money that's come in."

Most people in The Dalles don't know a wave of cryptocurrency is headed toward them.

That includes city leaders. "I'm not familiar with the issue," Mayor Stephen Lawrence tells WW.

The one exception: city councilor Taner Elliott, who also happens to be the electrician who installed the wiring at OregonMines.

While he was glad to have the work, he is concerned about the stability of the cryptocurrency business. "I just worry about the longevity of Bitcoin mining and whether or not it's going to be something that's sustainable," Elliott says. "You hear all the rumors about what the price is doing. I worry that it's a fad more than anything."

The man in The Dalles who gets to decide if he'll dole out power to miners is Paul Titus, lead engineer at the Northern Wasco County People's Utility District.

The PUD is a nonprofit electric company that gets 85 percent of its power from hydroelectricity generated by dams on the Columbia River.

On a recent Wednesday, Titus sat at a round table in his office, in a blue button-down shirt, jeans and New Balance sneakers, thumbing through a set of forms that he created specifically for people hoping to open up data centers in The Dalles.

For years, Thurber's OregonMines was the only cryptocurrency mine Titus had approved—because it was the only application he had received.

Last November, that changed. The value of Bitcoin spiked to more than $20,000—and Titus started getting a new inquiry every week from prospective miners.

"It was constant," he recalls. Most of them, he says, had inquired first in Washington's Chelan, Douglas and Grant counties—and were told those grids had no vacancy.

In 2017, nearly 200 miners applied for access to electricity in those rural counties in Washington state—just across the river from The Dalles. As Washington's power grids fill to capacity, miners are moving on to rural Oregon. The Wasco PUD now has 12 inquiries on file—with the largest of those miners asking for an amount of electricity each month that could otherwise light up 700 high schools.

"They are going to the least-cost provider first," Titus says, "and then working their way down the list."

In Washington, public utility districts have responded to overwhelming requests for power by restructuring rates to raise prices for cryptocurrency mines. The Northern Wasco County PUD is considering adopting similar measures, Titus says.

"Unless you are monitoring the issue," he says, "they could unexpectedly use the existing capacity."

A single AntMiner can use the same amount of power each month as a single-family home. And most data centers hold hundreds or even thousands of computers.

Even Thurber admits this is a lot to ask.

"At some point, you're no longer able to give stable power to the customer base who came there for the stable and cheap power," Thurber says.

Environmental advocates are far more alarmed. They warn that an increased demand on hydropower dams, which have a limited capacity, will require power users to turn to other sources. The second-largest source of power in Oregon is coal.

"It's not like there's a bunch of hydro megawatts sitting out there unused right now," says Brett VandenHeuvel, executive director of Columbia Riverkeeper, an environmental group. "We're already using all of it. If one company comes in and uses hydropower, that load is being replaced by some other generation somewhere else."

And the continued dependence on hydroelectric dams is a controversial question. The dams block the spawning runs of salmon—and Gov. Kate Brown has proposed reducing hydropower to keep the fish populations from dropping further.

"We're at a real fork in the road here where if we continue business as usual with the hydropower system, salmon will go extinct," Columbia Riverkeeper's VandenHeuvel says. Some runs of salmon could die off completely within the next 30 years, he adds.

And all of this leads to a more philosophical question. We know what Oregon can do for Bitcoin. But what can Bitcoin do for Oregon?

And what happens when the coin rush is over?

One hundred thirty miles south of The Dalles, in Bend, Jeffrey Henry says he's found an answer.

Henry, a former engineer and manager for cable TV companies such as Cox and Time Warner, opened his data center, Cascade Divide, in 2014 as a kind of shared space renting out computers to Bitcoin miners. (He won't say how many, citing security risks.)

His building feels like a bomb shelter: concrete floors reinforced with copper wire, 18-inch-thick walls, and an onsite backup generator with 2,200 gallons of diesel.

"When the zombies attack, they won't be able to get over the mountains," Henry says.

He's kidding: His real concern is earthquakes and tsunamis that could knock out the power and internet connections.

That's good for the cryptominers stacked in Henry's sophisticated data halls: The computers will never stop, giving them an edge in the race to find the remaining Bitcoins before time runs out.

"Some of these cryptocurrency miners just bought old warehouses—that's what we'd call a 'retrofit,'" he says. But his center is different. "Literally the whole world outside could shut down, and we could keep running for four days like nothing happened. That's what's important for state and local governments and companies."

Oregon's economic history is filled with examples of the exploitation of natural resources: fish, timber and, more recently, cheap hydropower.

For years, aluminum companies lined the Columbia. In more recent decades, tech companies have settled in Oregon for cheap land and, more importantly, cheap electricity—see Washington County's chip plants and the server farms Google, Facebook, Apple and others have plunked down along the Columbia.

But the latest industry to exploit Oregon's cheap electricity isn't producing jobs or economic growth on a similar scale.

McCullough, the energy consultant, calls Bitcoin his "favorite scam." He says cryptocurrency mines offer little benefit to Oregon in exchange for power use.

"It will get bigger as our [energy] prices continue to decline—until it all crashes," he says. "Building a server farm uses the same equipment and the same electricity, but produces something of use to society."

Thurber says that's far too glum a prediction. Once people get used to the idea of Bitcoin, he says, they will start to see its advantages. One day, the digital currency may feel as intuitive and natural as the internet itself.

"To some degree it might be a battle for minds first," he says. "And then it becomes a battle for hearts."

WTF is Bitcoin? Here's how it works, and how it could change the world.

The workings of Bitcoin remain mysterious to most outsiders, replete with jargon and confusing concepts. (We made a glossary. It's on page 19.) But like all currencies, it depends on some standard to assure users that the money has value.

The U.S. dollar relies on the authority of the Treasury Department. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies instead rely on complex mathematical equations.

There are a finite number of Bitcoins, and every time a new one is mined, bought or sold, that information is recorded using a digital ledger called the "blockchain." It's as if every dollar bill had a chip inside it that could tell you each time it changed hands.

New information gets added to the blockchain by computers "mining" for Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. They solve a complicated math problem to validate that each Bitcoin trade really happened.

So these computers, like the ones at OregonMines, are in a race. They're competing against other machines spread all over the world, in pockets of the Midwest, Puerto Rico, Iceland and China.

The first ones to solve a somewhat random mathematical puzzle—and in so doing, verify previous transactions—are rewarded with new Bitcoins. (Other cryptocurrencies, with names like Ethereum and Litecoin, work similarly.)

As more computers join the race, the puzzle gets harder to solve. When a computer successfully solves the problem, cryptocurrency is released and the computers move on to the next puzzle.

"In the early days, you could actually mine it using your home computer," Frank Nagle, a University of Southern California professor who studies economics, said in a Council on Foreign Relations podcast. "But today the problems have gotten so hard and so complex that if you tried to use a regular laptop or desktop, you probably wouldn't have a chance."

"So people are designing super-powerful computers that are purely used for helping to solve these problems in hopes of finding the next Bitcoin," Nagle says, "and if you do so, then immediately you are $10,000 richer."

In fact, the puzzles have become so complicated and there is so much competition to be first to find the answers, that miners are now teaming up in "pools" of super-powered computers that all work together to find a new block. The miners split the profits among the members of the pool.

To create scarcity, and therefore value, the Bitcoin algorithm limits the total number of coins to 21 million. Miners have found about 16 million of those coins since 2009, but because mining gets more difficult over time, it could take 50 years to find the remaining 5 million.

But eventually, the coins will run out and many cryptocurrency mines will be abandoned.

Bitcoin entrepreneurs respond to this ticking clock with a utopian vision. They say digital money could change the world.

"There's a lot of predictions," says Leif Shackelford, who mines Bitcoin and Ether in his Portland basement and has begun selling cryptomining equipment to others.

He believes in the blockchain technology, but has doubts whether it will succeed as a currency.

"I think the biggest potential for good that any of this could bring," he says, "is in finding a path to people owning and being responsible for their own data."

As for Terrence Thurber, the founder of OregonMines? He sees cryptocurrency as the answer to a variety of problems that the dollar creates in the online and global marketplaces. It will make trade easier, faster and more secure, he says.

But that only works if people trust the tech.

"We should probably wonder why these things are framed so negatively from the get-go," Thurber says. "The internet was not well-received in the '90s. It was going to ruin your kids. It was going to turn them into zombies. Fast forward 20 years, everyone and their mother can't help but use the internet every part of the day, no matter where they turn, and most of them love it."

Still confused? Here's a glossary of terms.

cryptocurrency: Any of the hundreds of digital currencies that use code-solving to create units of money and securely verify transactions.

Bitcoin: The first and best known cryptocurrency, created with what has become known as "blockchain" technology.

blockchain: This technology creates the method by which you can create and transfer currency around the world without banks or governments, in a legal manner that is also secure and highly decentralized. It's often called a publicly shared digital ledger. Think of it as a kind of digital quilt, in which each new block is like a fabric square, embroidered with the receipt of Bitcoin transactions and sewn into an ever-growing blanket. Literally speaking, a block is a record stating the location and amount of cryptocurrency. Once a block is completed, it's added to the chain of other records, creating a blockchain.

miner: A person who uses computers to solve the complicated math problems that verify transactions and add new blocks to the blockchain. On average, a new block is added to the Bitcoin blockchain every 10 minutes, releasing 12.5 new Bitcoins to the miner or miners who are first to solve the puzzle. Bitcoin miners are also compensated with transaction fees every time they find a block.

pools: Groups of miners who combine their resources to unlock new blocks and share the profits.

AntMiner: The product name of a popular Bitcoin mining computer built by hardware company Bitmain. All the specialized computers used to mine Bitcoin are often called AntMiners—even if they aren't really made by that company.

kilowatt-hour: A measure of electricity that equals consuming 1,000 watts for one hour. You could watch 29 movies on DVD with one kilowatt-hour of power.

megawatt-hour: The equivalent of 1,000 kilowatt-hours. An industrial-sized cryptocurrency miner can use anywhere from 2 to 100 megawatt-hours per hour.