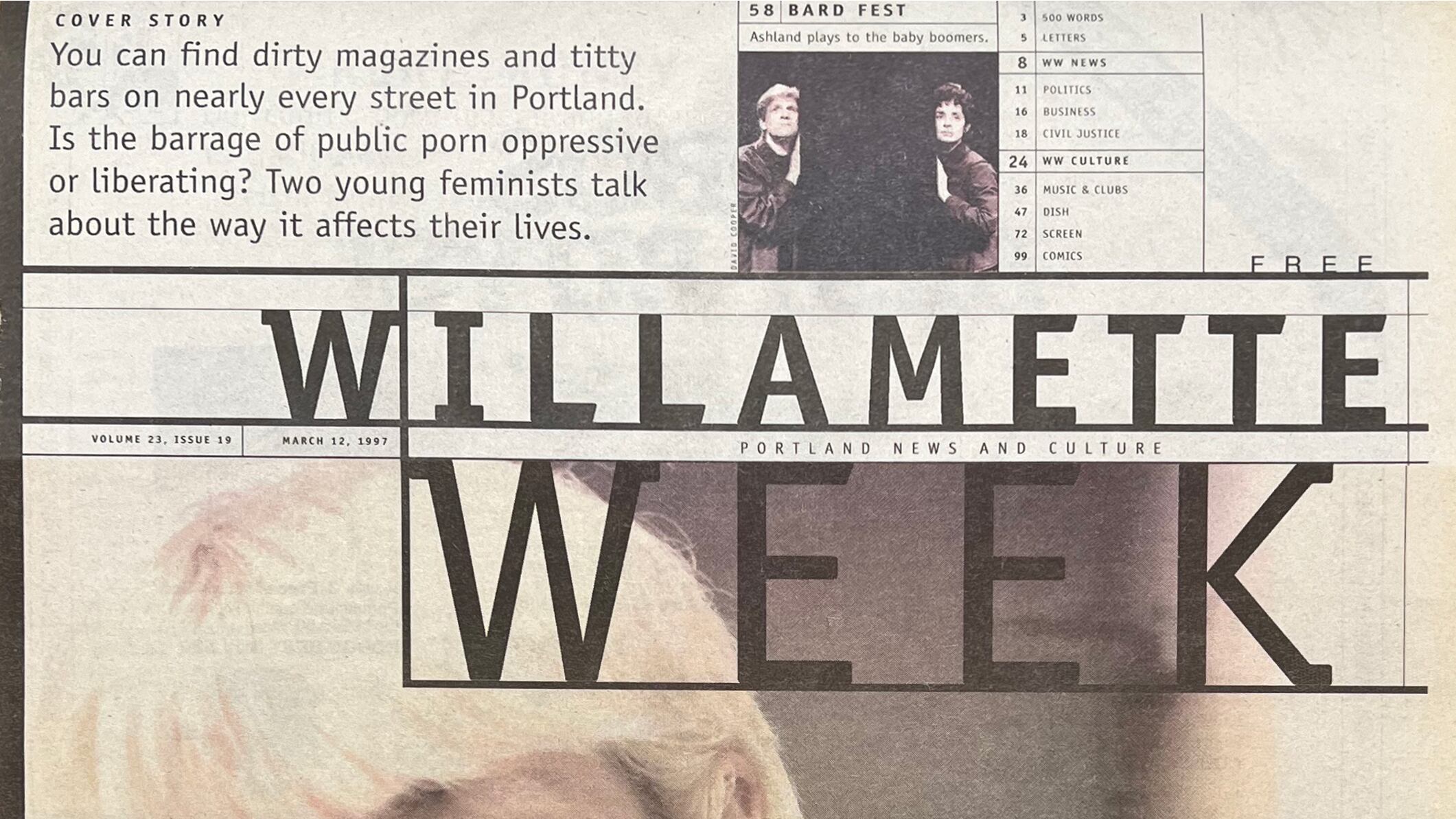

This story first appeared in the March 12, 1997, edition of Willamette Week under the headline “Porn: Two Views.”

The red velvet Magic Garden at 217 NW 4th Ave. doesn’t feel wholesome, but it isn’t threatening, either. It’s cozy. The blue-plate special is pot roast. A preppy young couple and a woman in a Skinny Puppy T-shirt sit toward the rear. Some well-dressed Asian men are parked directly in front of the already naked dancer, laying out fives and tens. Viva Las Vegas, a scrubbed blonde who’s sexy without being Barbieish, slinks around to Bow Wow Wow’s “I Want Candy” on a platform stage. Afterwards, she collects her thin stack of bills, slips into tight black bloomers, cracks some jokes and chats at the bar with a grandfatherly regular. The bloodshot guys at the back bar hump their chairs and wait for the next girl.

Scenes like this go on all day and all night in Portland, and there are few zoning or obscenity laws to prevent it.

Does the barrage of public pornography in Portland result in increased violence against women? Are men more likely to yell “nice ass” after an evening of watching naked dancers? Do magazine vending machines showing breasts on every corner lower women’s self-esteem?

Jill Portugal thinks so. The 23-year-old Brown University graduate moved here from New York about a year ago to work as a DJ for KNRK 94.7 FM. She has since quit that job and now writes TV news copy for $6.50 an hour. She also manufactures T-shirts with slogans like “Fuck Your Fascist Beauty Standards” and “Not Intended for Decorative Use.” Portugal wrote to Willamette Week after the Dec. 4, 1996, issue, in which a John Callahan cartoon depicted a mailbox stuffed with “Dead Feminists.”

“It’s not the first time Willamette Week has blithely printed something obnoxious and offensive to its female readership,” she wrote, in what would become the opening salvo in a war of words. “Oregon doesn’t exactly have a female-friendly climate, and feminism’s pretty comatose here.... For me, there’s nothing very freeing about living in a state whose consumer-to-porn ratio ranks the highest in the nation.... I abhor the porn industry with violent intensity. Because it exploits and hurts women. Because I believe it’s fundamentally impossible both to consume porn, and to respect women as people. And because Portland is so steeped in porn culture, I know I can’t stay here.”

Portugal’s bitter conviction inspired an exceptional amount of reader response. One man likened her to a witch “having a bad hair day.” Another said he has “greater respect for a woman who will dance naked in front of a group of strangers” than for one “who whines.” A more thoughtful response, however, came from 22-year-old Magic Garden dancer Viva Las Vegas.

Viva’s real name is Liv Osthus. She’s a Midwestern Lutheran minister’s daughter who moved to Portland about a year ago after graduating from Williams College in Massachusetts. Her letter (which appeared in the March 5 issue of WW) responded to Jill’s “self-righteous and misogynist opinions” about the porn industry. Liv has worked at the Magic Garden for six months and earns about $40 an hour during her five-hour shifts. Stripping, she says, has been a safe, viable and even empowering career that gives her lots of spare time and a means to pay off steep college loans. “Money is power,” she wrote. “You only become the victim when you call [yourself] that.”

Both women agree that porn is easily accessible in Portland. There are 42 titty bars in the Portland metro area, up from 18 in 1989. The golden year for stripping, though, was 1993, when there were 50 strip bars in Portland.

The recent decrease in the number of strip bars doesn’t indicate any slack in Portland’s sex industry. A Fantasy Video megastore opened on West Burnside Street in 1996, and erotic magazines such as Exotic and The T&A Times are displayed prominently on downtown street corners. One-on-one action in the form of live lingerie models is the trendiest new form of adult entertainment. The number of lingerie parlors has shot from two to 13 in the past three years. These are popular ventures, as the overhead is low and no liquor licenses are involved. For $40 to $80, guys get a private half-hour “modeling” session to jerk off to. Extra twenties can buy extra treatment; Portland Police already have charged several lingerie establishments with prostitution, according to Sgt. Ed Brumfield.

Porn’s impact on the female psyche is hard to measure. Jill Portugal firmly believes that the proliferation of adult businesses feeds a stereotype of women as sexual objects, most valuable when they’re naked. To Liv Osthus, the mainstream acceptance of porn is a healthy part of culture that provides lucrative employment and that embraces, rather than subverts, sexuality.

Can these two women, both of whom call themselves die-hard feminists, co-exist in Portland? How can two such different philosophies each fulfill the goals of feminism?

After some delicate negotiations, Portugal and Osthus agreed to meet at our offices to find out. Both of them worried that the discussion would turn into a public catfight. The talk was emotional—Liv burst into tears while talking about her parents—but not vicious. After 90 minutes of taped conversation, led by editorial assistant Brooke DeNisco and news editor John Schrag, the two women looked drained and in need of coffee. Nevertheless, they continued chatting for 45 minutes after the tape recorders clicked off. Here are excerpts from their conversation.

Willamette Week: Jill, when did you first start thinking seriously about pornography and its effect on women?

Jill Portugal: The way I remember it...I was at MTV as a summer intern, and MTV is in Times Square, where most of the porn theaters and porn shops are. As an intern, I was always being sent on runs through Times Square, and I was usually wearing a skirt because it was summer and an office environment, and I got harassed literally every time I left the building. I spent most of the summer really pissed off and thinking about why this was happening to me, and I made a connection between the area I was in—largely porn—and the way men were treating me there.

WW: Do you often write letters to publications?

Portugal: I do. If I read something that pisses me off, I write a letter to the editor. They usually don’t get printed.

I’m also a mentor to a 10-year-old girl. She lives right down the street from a strip bar, and I don’t think anyone should have to grow up next to a strip bar.

Liv Osthus: I don’t think a strip club should be right next to an elementary school. I think it’s in bad taste.

Portugal: I don’t know if it’s a zoning concern, but I personally like to be able to avoid these places. I’d rather I didn’t have to see them, because when I see something that upsets me it’ll upset me for a while. It interferes with my day. In New York, and every other place I’ve ever lived, you just avoid them. You don’t have to go to Times Square. Here you can’t avoid it. They’re everywhere, just sort of sprinkled throughout the city, and I don’t like it.

Osthus: Obviously there’s a market for it.

Portugal: I realize that.

Osthus: You think that porn isn’t necessary, that it’s an evil to society?

Portugal: Yes.

Osthus: You don’t think women do it by choice?

Portugal: I think there are a lot different reasons women get into the sex industry. I would say some of them are by choice, like, “I could be a schoolteacher, I could be a florist, but I ‘d rather be a stripper,” you know, but I don’t think that’s why the majority of people do it.

Osthus: Every woman that I work with is a die-hard feminist. A lot of them do it because of the scheduling, so they can raise families or be in school full-time and make enough money to survive and raise their kids. In their spare time, a lot of them work in women’s shelters. I’ve never been in a community of women who think so much about why society is the way it is. I went to Williams College, and what really frustrated me was that there were a lot of people talking all this rhetoric, but most of them had never taken a step in the real world and probably never would. Those were real white-collar, privileged kids who just accepted the MacKinnon/Dworkin sentiment, and I really think it has become the accepted rhetoric: Heterosexual sex is inherently violent, so porn is a form of rape.

Portugal: This is what you’re saying that they say?

Osthus: I‘m saying this is what feminism is today. That’s why there’s a lot of backlash and that’s why there’s a Callahan cartoon.... I think feminism right now is very polarizing; it’s lesbian groups, it’s radical lesbian groups, and it’s very polarizing. A lot of women can’t call themselves feminists and be accepted by the movement.

I work with a lot of feminist women at the Magic Garden. A lot of the jobs out there are just mind-numbing and soul-numbing. I wrote to my professors at Williams that this is the least-degrading job I could find. They wrote back, “We’re so proud of you. We’re glad you’re putting your knowledge to creative and artistic use.” That’s an exact quote. In my mind, a feminist is a free-thinking woman, period, the end.

WW: Jill, do you see anything inconsistent with being a feminist and doing what Liv does?

Portugal: Yes. I have a broader definition of what it means to be a feminist. Something like what’s in the dictionary. You know, total equality between women and men. Liv, when you say being a free-thinking woman, I think you basically mean doing what’s best for you. My problem with that is that I believe you have an effect on the world around you. Personally, I’d like your world to be separate from my world. I’d prefer if we could all have our own things that we wanted to do and not affect other people adversely, but I don’t believe that’s what happens. I believe the existence of strip bars and porn magazines and adult videos and lots of advertising and basically a lot of stuff in the world has an effect on my life.

Osthus: I take great offense at that; I mean, the world revolves around sex and our own sexual interactions. A lot of what you call harassment is just normal sexual banter between the human species. It goes on in every culture around the world.

Portugal: Yeah. I know that, but if someone doesn’t know me, they have no right to talk to me in a sexual way. I choose not to be defined exclusively by my sexuality. I have sex, but that’s not my identity as a person. I can do a lot of other things…I can write. I can knit, you know. I can design T-shirts. There’s a lot of things I can do, and I don’t want my primary identity as Jill to be “Jill, she’s the one with the tits.” You basically have accepted the fact that you are being defined by your sexuality.

Osthus: Not at all. I mean, I consider what I do an art form. I honestly do. I ‘d like to invite you down to my club to watch me do what I do. I consider it an art form.

Portugal: OK, you may not think that you are defining yourself that way, but do you really think that the men are getting the same thing out of it that you are?

Osthus: Certainly.

Portugal: Are men thinking, “God, I wonder what her favorite authors are”?

Osthus: They ask me that on stage. Have you ever been to a strip bar?

Portugal: No, I’ve been near them.

Osthus: I’ve never felt degraded by men in there. I’ve never, ever felt harassed. We’re performers, like a ballerina is a performer. [For men who watch], I think it’s a form of release.

Portugal: OK, so the existence of porn is a cathartic release? OK, so that means that [if we had] a lot of porn, we wouldn’t have a lot of rapes, wouldn’t have a lot of sexual abuse. I mean, how do you rationalize the fact that there’s lots of porn [and] lots of rapes?

Osthus: Well, porn has never been linked to rapes. If you read recent studies, they all pretty much clear pornography. They say that rape is not an act of sexuality. It’s an act of violence.

Portugal: Look, I would totally approve of your life and all of your friends if I didn’t feel that it affected me in a way that I don’t want to be affected. I have to live in this country, too. I don’t have to live in this city, you know, and I probably won’t for very much longer, but I do have to interact with people. I have to have these experiences where I can’t wait for the bus by the side of the street without two guys in a truck driving by and shouting at me. I can’t walk home from my job at night when they make me work the late shift without some guy shouting at me from across the street, trying to scare me. I’ve had all this happen. Why? I feel that the existence of [strip bars and vending machines] leads men to view all women in these ways. I don’t think they make a distinction between me and you. If we’re walking down the street together, they wouldn’t be like, “Oh, she’s a stripper, I can say shit to her, and she’s not, so I’ll leave her alone.” They just see all women as things to be looked at.

Osthus: If you came into my club, that certainly wouldn’t happen to you. There’s boundaries that are respected in those places.

Portugal: I don’t understand why men feel like it’s easier to talk to naked women. You know what I mean, it’s some kind of a power thing.

Osthus: A lot of the traditional definitions of power don’t mean shit. It’s like, a lot of these guys who come in are heads of their companies. They have a lot of power, a lot of people work for them, but when they come to a strip club they have no more power than the Mexican at the rack [the stage-side seats].

Portugal: A friend was telling me that Henry Rollins, when he was on his speaking tour, basically said something to the effect of, “You think you’ve got all the power because you’re up on stage and everyone’s looking at you and that’s like feminine power, but what kind of power would you have if there was no bouncer or bodyguard and you were in a room naked with 40 men?”

Osthus: Human relations—sexuality—it permeates everything. You can’t hide from it. You can make yourself a victim of it by calling yourself a victim. And that’s where I think it’s gotta stop. I mean, feminism labels women “victims.” It does not empower them, it takes their power away by doing that.

WW: You both have lived a lot of different places. You’re both relatively new to Portland. You’ve got different views about the atmosphere here for women. Jill, one of the things you touched on in your letter was that Portland is not a very good place to live if you’re a woman, that there’s more objectification of women here than in other places, and that you feel less safe here.

Portugal: You know, I probably shouldn’t have said that. I don’t feel less safe here. I feel that the climate, in general, the fact that there’s such a proliferation of strip bars and vending machines, makes me feel less valued here as a person.

WW: Vending machines?

Portugal: The Exotic and T&A Times. They just really bother me. I called the DA’s office last week to see how that was legal, because there are laws in America that if you’re 18 or under you can’t buy porn. I don’t understand how vending machines, which don’t ask for I.D., could be legal. The DA went and researched it and basically said there’s all these little loopholes. If one of those vending machines was in my office lunchroom, I could sue for hostile environment. I feel like, if you extend that, then this is a hostile environment because I see three of those boxes on my way to work every day. I shouldn’t have to see that. I don’t want to.

WW: Do you feel like you are hassled more in Portland than other places you’ve lived?

Portugal: Well, I’ve been thinking a lot about that lately, because I was hassled a lot over the summer, and it was making me tense. Then I started wearing a Walkman and I don’t look at anybody. I can’t stop anyone from looking at me. I can’t stop anyone from talking to me, but if I wear a Walkman I don’t have to hear them.

But a lot of the worst things that have happened to me happened in New York. I’ve had my ass grabbed in the middle of the street in the East Village. I’ve had people ask me if my breasts were real when I was trying to get a bus. I’ve been harassed like two steps away from my house in Providence, Rhode Island. I’ve been assaulted in Italy, but that’s Italy. I don’t know if I should count that. But basically I think the problem is that most men don’t understand that women don’t want it. They think that it’s a compliment. The way I feel is that if you get an ego boost out of some random guy telling you you have nice legs, you’ve got a self-esteem problem. Because I don’t need some random guy at the bus stop to make me feel good about myself. I do anyway.

Osthus: Do you turn around and tell them you’re offended?

Portugal: I tell people to fuck off. I spit at people.

Osthus: It happens everywhere around the world, and it’s only a certain type of men who do it, and I don’t think they’re necessarily attached to the porn industry.

Portugal: I mean, porn is not the only thing that I worry about, or I think about, or I care about. I’m worried about the self-esteem of young girls. I want to do something about that. I worry about sexual harassment in the schools, because that happened to me in high school and I didn’t do anything about it, because I didn’t know that I could, and I want more girls to know that they can do something about it. So I do have other issues. It’s not like I’m this anti-porn crusader.

Osthus: Here’s my personal anecdote: I didn’t even realize that women had hair on their vaginas until I saw a Hustler in my brother’s room. It was a part of my sex education. To my mind, porn glorifies and celebrates the body more than degrades it. And to me, Vogue magazine, where there are these bodiless heads, is much more offensive than a woman who’s got her legs spread. What is wrong with women enjoying themselves, enjoying sex?

Portugal: How do you know that they’re all enjoying themselves?

Osthus: It’s the idea that there’s something wrong with women enjoying sex. That the porn industry is degrading and sex is violent.

Portugal: This is going off on another tangent, but the whole thing about the women who work in the industry...I want to know why in America women are more valuable when they’re naked. Why do I make $6.50 an hour writing a news story and you make, what is it, $40 an hour?

Osthus: I do learn a lot more than I have at any other job. More than I did at Williams fucking College. What year did you graduate?

Portugal: ‘95. What year did you graduate?

Osthus: ‘96.

Portugal: You say that you’re not in it for the money—would you do it for minimum wage?

Osthus: Definitely I would.

Portugal: You would. So you really like what you’re doing, and if the money aspect was separated from it—if you’re making $4.50—you would still do it.

Osthus: I’d certainly rather do it than data entry. Those are a lot of the jobs that are available to people with liberal arts degrees.

Portugal: Do you have a degree?

Osthus: Anthropology.

Portugal: I have an English degree.

Osthus: Even more useless.

Portugal: Yeah.

WW: What is the typical response when people find out what you do?

Osthus: To people in my age group, a lot of them think it’s really cool. I go into Fellini and everyone’s like “Hi, how are you?” And adults, I try to be really open with them. A lot of them support what I’m doing. I try to explain to them that it’s an art form. It’s kind of an unusual thing for someone of my background to be doing.

WW: It’s interesting that you both have these very different viewpoints, and are acting out your views in different ways, yet both of your parents seem to wish you were a little bit more middle-of-the-road.

Osthus: A lawyer or doctor.

Portugal: Yeah.

WW: Why is that? Is it a generational thing?

Portugal: I think it’s just sort of a not-making-waves kind of thing. They’d like me to be a little more mainstream. You know, my mom considers herself a feminist, but I feel like she doesn’t think about these things because she lives in New Jersey, she lives in the suburbs, she has a car, and when she wants to go somewhere she just gets in the car and gets out—she doesn’t have to deal with what’s going on in America. She has a very insular lifestyle. When I talk to my parents about what I am doing, they’re just like, “Well, as long as you don’t let it affect your relationships with men...I guess it’ll be OK.” They asked me if I was a lesbian. I said, call my boyfriend and ask him. I don’t think they want me to be as extreme as I am. They’d rather me be a lawyer or something. They think that I should be doing something else with my time, but I don’t care. They’re just afraid I’m going to turn into Valerie Solanas.

Osthus: My parents want me to live a secure life and be happy. I’ve tried their version of happiness, and I’ve struggled a lot with my parents and their traditional notion of success. I’ve always tried to be the best at whatever it is I did, and I’ve always wanted to be an artist or a performer. I told them I was doing this because I’m very proud of what I do and want to express my ideas in a public forum, even though I’m still working on them. And I told them that I’m interested in the sociology of it and developing my art form. They’re very ashamed of it. Very frightened of what I’m doing. They want me to be safe and work 9 to 5 and be happy. My Dad was hurt when I told him. It was the only time he ever raised his voice at me. He said, “You’re making money off of other people’s lust.” A pastor thing to say.

WW: Will you look back on this part of your life without regret or embarrassment?

Osthus: I am awfully proud of it. I’m proud of doing it. It’s something I believe in. I’m open about it. I think that we’re making important sociological change, and I think I’m a hard-core feminist. My parents are of a different generation, and they often think I’m doing things the wrong way.

WW: Jill, you work for television, which many people think does far more to degrade and cast women as one-dimensional creatures than do strip bars.

Portugal: I just happen to have this job right now. It’s not like all my life I’ve wanted to be a TV person. I just got out of radio and got into this. I happen to like what I do, because I write and that hasn’t happened in a long time, and the people are nice to me and I get along with everybody.

Osthus: I feel like TV has much larger social ramifications than what I do.

Portugal: I’m not trying to say that you and your club are single-handedly responsible for all that’s wrong. A lot of things are involved. Yeah. I see those shows at work and I’d like to turn them off.

Osthus: That’s ironic. So, you’re prostituting yourself, which is what I’d call it.

Portugal: Well then, everyone in the country is a prostitute. What are you going to do?

Osthus: My job, I know where the dollar bills come from. It isn’t big business. We’re not raping Third World cultures and nations. And also, television has been linked to rape more than porn has.

Portugal: It seems like we both work at places that perpetuate stereotypes of women, although I don’t really make the big decisions at my place.

Osthus: Yeah, and I feel like I’m working toward a better stereotype. The guys coming in there are getting a lot more than a naked body when they come to see me, and if they don’t like it, too bad. The Portland strip scene is very pro-women and women’s rights. The women who do Danzine are working on needle-exchange programs, working to get women out of the streets. They are grass-roots activists all the way, and it’s really important to the community here to have [stripping] seen more as a form of expression, and at the same time, to use our time and our power and our knowledge to do good for other women.

Portugal: I’m just for whatever is the most good for the most people. More naked women on billboards or in strip clubs—I don’t understand how that’s good. I just want to get away from the idea of woman as hypersexualized—all she wants to do is fuck. That’s not why I‘m here. I‘m here for a lot of other reasons.