The latest movie directed by Ben Affleck, Air, tells the story of how the Beaverton sneaker underdog Nike leapt into a partnership with Michael Jordan in 1984. The picture, which opened to positive reviews from critics, including our own, credits Nike’s decision to sign Jordan largely to vision of one man: basketball promoter Sonny Vaccaro, played by Matt Damon.

Meanwhile, Jason Bateman plays Nike’s marketing director, Robert J. Strasser, as an anxious, attentive middle manager who fears the risk of dedicating the company’s full basketball budget to Jordan. Bateman has very good hair, and he spends most of the movie pulling it out.

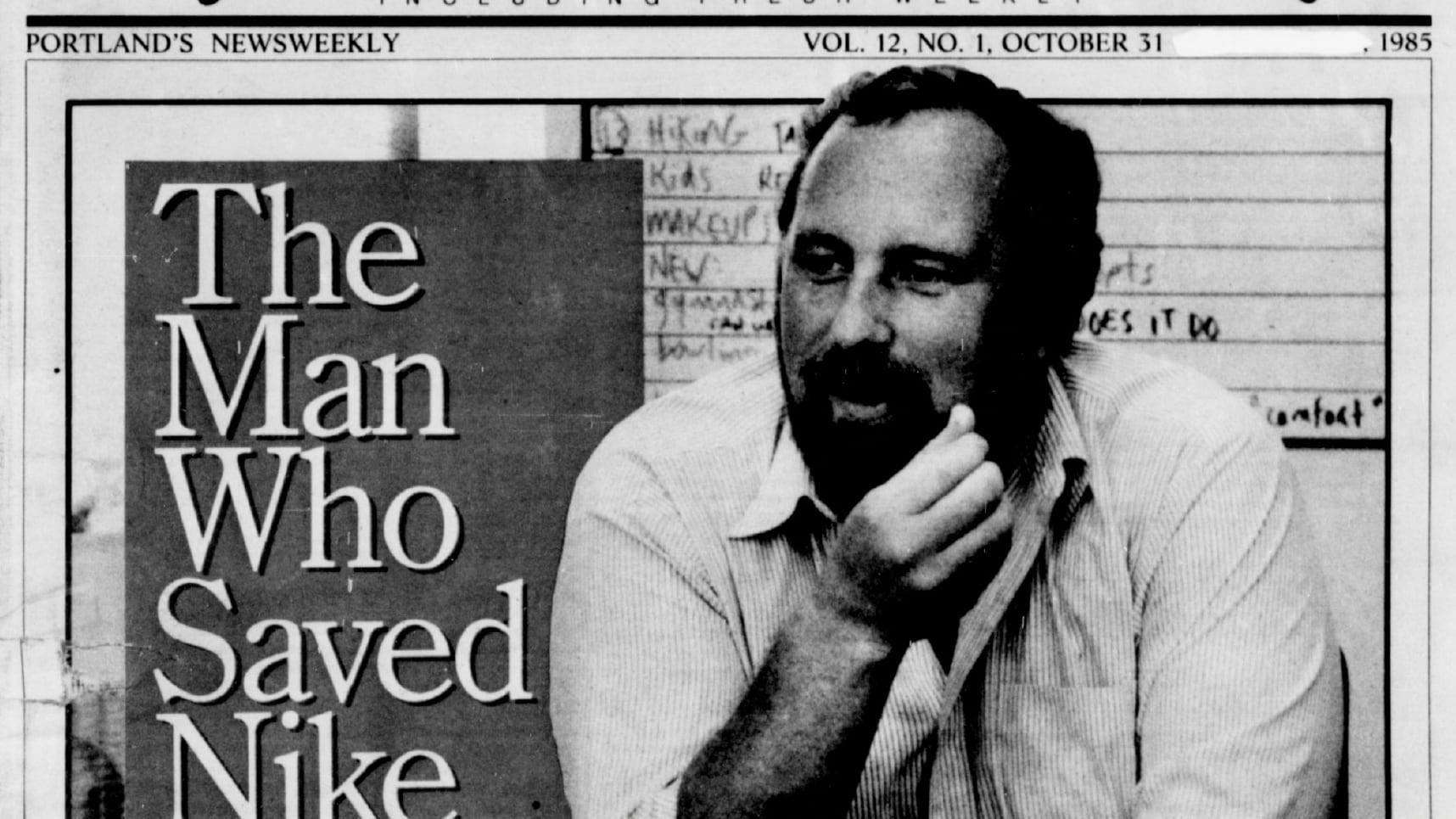

In reality, Strasser was not such a shrinking violet. He was a loud, demanding troublemaker who liked to rattle people’s cages and blow expense accounts on lavish parties. And he played a much more pivotal role in the Air Jordan campaign than the movie suggests. In 1985, business reporter Mark Zusman profiled Strasser on the cover of WW. He found a man who reshaped the company to revolve around marketing athletes to sell shoes. ”Remember what we are,” one executive told Zusman. “A marketing company.”

Here is how Nike’s brain trust described the greatest coup in company history one year after it happened. —Aaron Mesh, managing editor

This story first appeared in the Oct. 31, 1985, issue of WW.

It’s four o’clock on a Friday afternoon and Robert J. Strasser is sitting in an office the size of a small garage, an office painted on the outside to resemble an oversized black Nike shoe box. There’s even a huge replica of the firm’s trademark swoosh on one side.

The task at hand this particular afternoon: picking the color of the sole of a new tennis shoe. The product of two years of research and development, the high-performance shoe has a polyurethane sole that is 40 grams lighter than anything else on the market. In a business where fashion is at least as important as function, even something as seemingly innocuous as the color of a sole is no idle matter. In fact, at many companies this sort of decision would be made only after extensive market research. But Strasser has his own method.

In his office sits much of Nike’s brain trust, including Vice President Ron Nelson, Vice President Harry Carsh, chief designer and creative guru Peter Moore, and Strasser — at 38 the man credited by many with Nike’s recent turnaround and a fellow who is, by his own admission, “loud, obnoxious and fat.” Strasser sits at the head of a dark green table and fingers half a dozen prototypes of the tennis shoe, each with a different-colored sole, from jet black to bright day-glow red to a subtle gray.

“This one is hot,” barks Strasser, holding up the black sole.

“Black soles on a tennis court?” questions a shoe designer.

“These black soles won’t mark the courts.”

“Yeah, but courts have signs that say, ‘no black soles.’”

“That’s on private tennis courts,” claims Strasser. “Do they have those signs on public courts?” Then just as quickly he snatches up the bright-red sole. “This is cool.”

“It’s too cartoony,” offers Peter Moore. “I like these,” holding the gray-soled shoes.

“What do you think?’’ yells Strasser, who by the force of his voice draws Tom Clark into the office.

Clark, a project manager for the running division, offers, “I like red, but not for a tennis shoe. The problem with a color like this is that no one will think it’s a serious tennis shoe.”

“I think this one’s it,” booms Strasser with finality as he lifts the gray-soled shoe.

Strasser’s office, located in the Nimbus Oaks Business Park, a short distance from Washington Square, is several miles from Nike’s Beaverton corporate headquarters, where founder and chief executive officer Phil Knight, among others, can be found. But here at Nimbus Oaks, in a low-slung, brightly colored building, resides what many observers consider the heart and soul and, to a good degree, the future of Nike.

For a company that had grown faster than all but a few in recent American corporate history, Nike’s unexpected fall from grace last year was tough to swallow. The boom in the running market peaked, earnings were way off, the stock price plummeted, and, equally embarrassing, a couple of competitors carved out sizable niches in new markets — such as aerobics footwear — that Nike was either too lazy or too stupid to go after.

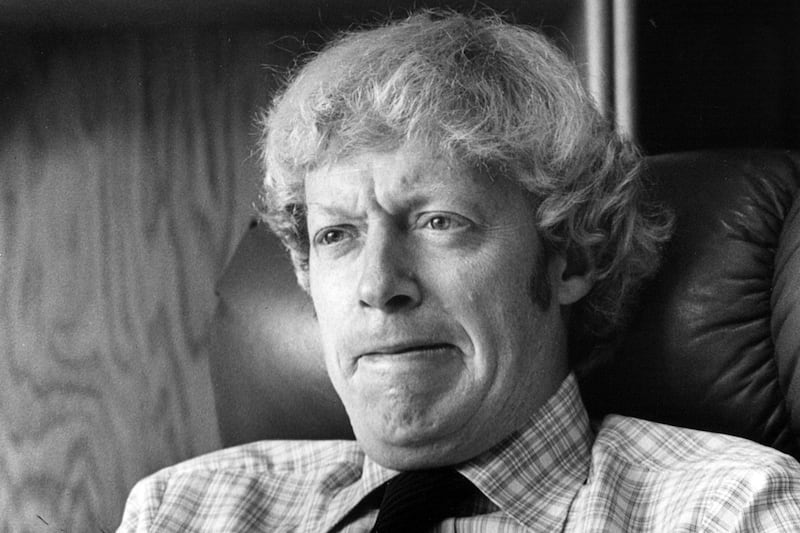

But in recent months the blush has returned to the rose. Earnings are back, the stock has regained its strength, and the investment community is bullish about the company’s future. While anybody who knows anything about this footwear and apparel company knows that Phil Knight is the driving force, the father, son and holy ghost of this remarkable firm, those who really understand Nike know how important a role Robert J. Strasser has played.

Oddly enough. Strasser is not of the mold of slightly aging jocks that so typifies most Nike employees. A man whose reputation for genius is matched only by the controversy that surrounds him, Strasser prefers partying to running and would rather watch a basketball game on cable than slip on a pair of Air Jordans and practice his jumper. Strasser has long played a key role as the marketing inspiration of a market-driven company — a role that has led to almost as many blunders as triumphs. But his recent performance in bringing about Air Jordan, a line of basketball shoes and related apparel that may well become the most successful single product in Nike history, is winning him new accolades for reinvigorating a company that had grown too bureaucratic and too smug. “A whole lot of people are responsible,” says CEO and president Knight about the firm’s recent turnaround, “but Rob is the MVP.”

Marketing is a term that, as a general matter, describes the variety of functions involved in bringing a commodity to the consumer: design, promotion, advertising, sales strategy and so on. Perhaps a more useful, and certainly more elegant, description of marketing comes from Peter Drucker, the noted business-management expert. Marketing, he has said, is “antithetical to selling. The aim of marketing is to make selling superfluous. It is to know and understand the customer so well that the product or service fits him and sells itself.” While there are numerous reasons for Nike’s success over the years, the firm’s greatest strength has always existed in the realm Drucker describes. Nike is, at heart, a marketing company.

Some dispute that, insisting that Nike’s success is due to the superior quality of its products. There is no denying the company’s penchant for innovation — witness the waffle sole, the elevated heel, the air sole, the padded backtab and, most recently, the sock racer. But there also is no denying Nike’s success in creating an atmosphere in which consumers believed that they just had to have Nikes. Marketing. And while people at Nike are as disdainful about taking credit for something as they are about titles, few deny the central role that Rob Strasser has played as chief marketer. Says Tim Renn, a former public-relations man for Nike who now works for the Portland Trail Blazers basketball team, “Without Rob Strasser, Nike would just be a running company.” Says another former employee, “Nike is the Miami Vice of the fitness business and Strasser is the keeper of the flame.”

Described by friends and foes alike as unpredictable, rash and at the same time tremendously charismatic, Strasser seems tailor made for a company whose approach to business always has been unconventional. For example, instead of public-opinion surveys, market research and demographic studies, the tools used by most market-driven firms, Nike relies more on instinct. A number of observers suggest that this altitude is a function of the company’s corporate culture — its irreverent, write-your-own-rules style of doing business. Phil Knight agrees in part with this explanation but is quick to add, “The little market research we have done has been pretty unsuccessful.”

“Then again, I guess we will never be as successful as the New Coke,” Knight says in reference to the product that, despite millions of dollars in market research, was unable to replace the original Coca-Cola formula.

“Nike is driven by the whims of a few people in upper management. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen,” says Michele Gaedke, who worked for Nike in tennis promotions until she became director of promotions for Avia Athletic Footwear, a Portland-based upstart that depends much more on traditional market analysis. Says Gaedke of her old firm, “There’s a lot of magic to what they do.”

And the lead magician always has been Strasser. Even Knight acknowledges that Strasser “has much more of a creative flair than I do.”

Creative or not, there is little doubt about Strasser’s flair. Portland is littered with ex-Nike employees who are more than happy to pass on their favorite stories about him. Such as the time he bounced a swivel chair off an executive desk just to make a point. Or how once in an airport terminal, Strasser, dressed in a Hawaiian luau shirt, white Bermuda shorts, Raiders of the Lost Ark hat and oversized belt buckle, became so frustrated with his inability to pass the the metal detector test that he simply dropped his trousers. How he has burned people out, demanded incredible loyalty, and then fired them at whim. How, at a pre-Olympics party held at New York’s Studio 54, a shirt-sleeved Strasser stood in front of 600 well-dressed shoe dealers and the first words out of his mouth were a none-too-polite “Shut up.” Says one former employee, “If Strasser was walking through a kitchen he would turn up the heat on the stove and rattle a few pans.” Says Nike designer Geoff Hollister, one of the very first Nike employees, “He’s not called Rolling Thunder for nothing.”

Raising the Stakes

Strasser surfaced in the early ’70s when his law firm was retained to do battle with Onitsuka Tiger. A Japanese shoe manufacturer, Tiger had begun to question its working relationship with a company named Blue Ribbon Sports. Strasser, the junior law partner not that long out of Boalt Hall at Berkeley, took it to court, winning a victory that most remember as nothing short of brilliant. Tiger and Blue Ribbon Sports broke up. Nike became the new name of Blue Ribbon and Strasser became general counsel. Before long he left the practice of law and came to work for Knight. And while he now is receiving the credit for the firm’s recent turnaround, Strasser has long been a major force at Nike.

Strasser’s role at Nike has been described in a number of ways (“Phil Knight may be the czar,” says one employee, “but Strasser is his Rasputin”), but it is best characterized as a catalytic one. “He will walk into a room and create havoc,” says Nelson Ferris, another longtime employee. Out of that havoc come the ideas that drive the company.

Even before Strasser joined the company, Phil Knight had spread the gospel that the best way to promote Nike was to get athletes to wear the company’s shoes. But once Strasser came aboard, the stakes got higher. Nike realized that a Sports Illustrated cover of John McEnroe wearing Nikes was worth 20 full-page ads inside. Getting the swoosh to be a trademark as recognizable as the Golden Arches, having it be associated with excellence and a certain, undefinable spirit — that was the marketing plan. And the weapon: money. Gobs of it.

One thing about Strasser — he was good at spending money. He was legendary for his annual sales meetings, extravaganzas such as the one in Big Sky, Mont., where, among other things, he staged a laser show on the side of a mountain. Strasser, who earned $150,000 last year, is renowned for his parties, such as the post-Olympics bash he threw in Hollywood where he rented a movie studio and paid Randy Newman to entertain — all for a cool million dollars. And people still talk about his ability to run up a $5,000 bar bill in world-class time. “Whenever things were over budget,” one associate said, “you could be sure it was Rob.”

But nowhere did Strasser spend as much money as he did buying athletes. On the pros, he spent lavishly. Adidas had, even before Nike, paid some athletes to wear their shoes. But Strasser shifted the gears of the game into overdrive, and in so doing revolutionized the way in which people thought about marketing shoes.

Strasser wanted pro basketball players to wear Nikes and by 1982, fully 65 percent of the NBA’s starters did. In the early days, Nike could get players like Elvin Hayes and Paul Westphal for a steady supply of shoes and a few bucks. But by the early ’80s it was considered a coup when Nike convinced Philadelphia 76er Moses Malone to give up his contract with Converse and slip on a pair of swooshes — for $1 million. “We were the company that started the price wars,” concedes John Phillips, who for many years headed Nike’s basketball promotions.

Strasser wasn’t satisfied with just professional athletes. He also wanted college players. He knew that while the markets they played in weren’t quite as large as those of pro teams, college athletes could inspire more passion and even more desire for imitation than could their pro counterparts. In a move that some have criticized as an unnecessary commercialization of amateur athletics, Strasser put men such as Georgetown basketball coach John Thompson on the payroll. Guess what shoes Georgetown center Pat Ewing wore during his college career?

In football, Strasser developed a one-year plan to go after the coaches and trainers of the top 20 college football teams in America, teams such as Texas, U.S.C., Oklahoma and Notre Dame. He put them on the payroll and called them consultants. The following September, 16 of the top 20 teams ran onto the field in Nikes.

Nor did Strasser stop with athletes. He knew that the entertainment industry offered the same kind of exposure that sports did. Nike opened a Hollywood office, gave out barrels of free shoes and threw lots of parties. And to this day, Nike has a woman in Hollywood who spends half her week reading movie scripts, determining which characters in upcoming productions just might like to have complimentary pairs of shoes. It was no accident that Sylvester Stallone wore Nikes in Rocky.

The Runner Stumbles

By the early 1980s, Nike had grown larger than anyone could have anticipated. Strasser’s effort to get Nikes on all the right people’s feet had succeeded. It didn’t even matter that he occasionally spent far too much money getting an endorsement contract from an athlete whose career never amounted to much. The firm was making 30, 40 and even 50 million pairs of shoes a year and was getting into the apparel business in a big way. In addition, in 1980, Nike went public with a stock offering, immediately making a select few employees, including Strasser, millionaires and making Phil Knight one of the richest men in the country. Not long after that, the company — and Strasser — began to stumble.

Many of the mistakes were unrelated to the product, but instead were a function of the company’s sudden wealth. Expense accounts got out of hand. Inventory was built up far too high. The payroll became padded with employees Nike didn’t really need. “If you have as many cheap victories as we did,” says Strasser, “you get cool and arrogant. You even begin to walk different.”

A similar altitude carried over to those parts of the company that were responsible for product development. Nike continued to generate new products, but many were failures. Strasser came up with the idea for a flashy disco shoe that was a total flop, even eclipsing his earlier $600,000 purchase of Brazilian T-shirts that, after a first washing, wouldn’t fit around your nose. Strasser also decided to get into the publishing business, purchasing a running magazine that he hoped would be able to draw advertising from competitors. It didn’t. By far Nike’s biggest mistake (though Strasser doesn’t get the credit for this one) was its stab at the fashion business, with a line of leisure shoes — women’s fashion shoes, slipper-mocassins — that was a disaster. Says Strasser, “It was like we woke up one morning and thought we were Greta Garbo. We’re not.”

Even worse than the products Nike did develop were the opportunities it missed. By the early ’80s, the running boom — Nike’s bread and butter — had leveled off. Yet Nike failed to move aggressively into other areas. When the aerobics craze took off, Nike was nowhere and two companies, Reebok and Avia, moved in.

Many of Nike’s problems developed during a 12-month period that Phil Knight was on sabbatical. Anxious to get away from the day-to-day affairs of the company, he had stepped aside and appointed Robert Woodell, one of the original Nike founders, as president. In September 1984, Phil Knight returned to the fold. As Knight wrote in the annual report, “George Orwell was right. 1984 was a bad year.”

Knight moved quickly. Inventory was slashed — some of it by selling to “undertakers,” barter houses that turn around and dump the shoes to discount shops. Management was reshuffled. The number of athletes receiving endorsement money was reduced from 1,100 to 600. The company’s payroll was reduced by 400 out of a worldwide force of 4,400. And some of the perks were removed. The Christmas party was eliminated. The budget for the Nike Times, the in-house newspaper, was hacked.

Knight recognized that his firm had become too bureaucratic and too sluggish. The various divisions in the company had become so ingrown that they placed almost impossible hurdles in the way of Nike being Nike: developing innovative products. Flow charts, production schedules, meetings and more meetings had made the product-development part of the business a slave to the rest of the firm. The result was a company that was unable to react to the marketplace. So Knight unleashed Strasser, a man said to be responsible for many of the mistakes the company had made.

Soon after Knight resumed the presidency, he announced the creation of a new-products division and chose Strasser as its chief. Because of his close relationship with Knight as well as his overpowering personality, Strasser quickly made clear that the tail would be wagging the dog no more. “He’s very loud in all his emotions,” says Knight, “and so he gets a lot of attention. He can get a message across without a lot of memos.”

Air Jordan

One thing Strasser didn’t do was waste time. For months the firm had been struggling with its identity, unsure of what it was and what it wanted to be. Knight and Strasser did know that the generic kinds of promotion and advertising that had long been Nike’s standard (posters and commercials of athletes wearing the product; beautifully designed but somewhat esoteric and vague ads with catchy phrases such as “there is no finish line”) had outlived their usefulness. Then, in addition to Nike’s decision to go after markets it had long ignored, Strasser began plotting to tie specific product lines with specific athletes. They introduced a line of shoes and apparel tied to John McEnroe, and baseball phenom Dwight Gooden. And then there came Michael Jordan.

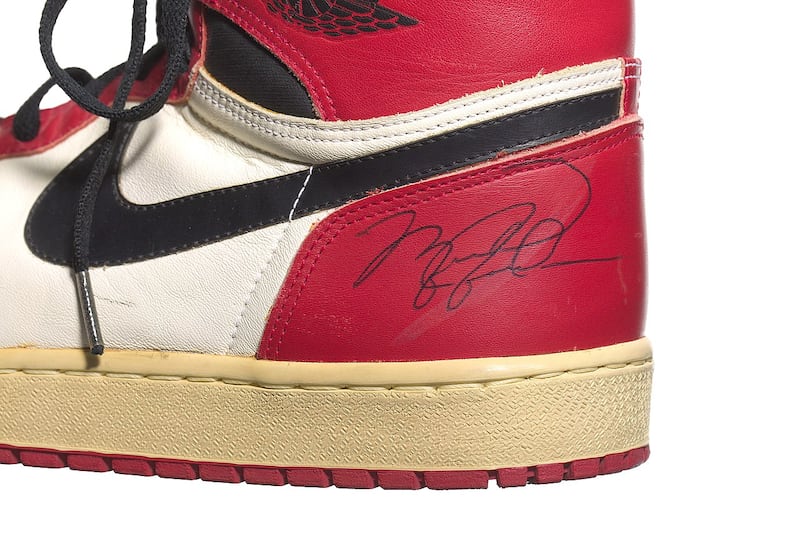

In retrospect, Air Jordan was something of a risk. In addition to investing a good deal of its reputation, Nike also was spending $500,000 on a contract with the Chicago Bulls rookie, a few million more in promotion and advertising, and several million more in production commitments. Sure, Jordan was an articulate and attractive athlete with supernatural jumping skills. But he had yet to play a season in the National Basketball Association. Nike’s market research? Strasser and company spoke with a few coaches, flew Jordan and his family to Portland for an interview, and then decided to go for it.

In April of this year, Nike introduced the new line. The centerpiece was a pair of colorful high-top basketball shoes that retailed for just under $70. But the Air Jordan line included everything from infant sleepers to gym bags, warm-up suits to muscle shirts.

The success of the Air Jordan line cannot be measured in mere numbers, although with orders of $130 million, those numbers cannot be ignored. And while it’s difficult to break out exactly the way in which the Air Jordan campaign affected Nike’s bottom line, it certainly is related somewhat to Nike’s recent quarterly earnings: profits of $24 million, three times the earnings for the same quarter last year. But the sweetness in the air at Nike these days is not simply a function of profits. It’s because of the recognition that Air Jordan was a perfect match, of apparel with footwear and of athlete with company. Pure marketing. But with no market research. “What Strasser has done with new-product development is extraordinary,” says Keri Christenfeld, a footwear analyst with Montgomery Securities in San Francisco. “From concept to production, Air Jordan was brought out in approximately four months. And it has created more excitement in the athletic footwear market than anything I can think of.” (Strasser was hoping to eclipse Air Jordan with a product line — called Road Warrior — tied to Patrick Ewing, the rookie basketball center who wore Nikes in college. However, Nike lost out in the bidding wars to Adidas.)

Strasser himself seems less excited about Air Jordan than he does the process that brought it about, a process that will lead, next year, to the introduction of a golf-shoe line — perfect for the “yupsters,” Strasser says — and a college-colors program that will market shoes and apparel to major universities. At Nike these days there is little doubt that product is king. In his view, the company is again willing to re-create the spirit that once made it great. “Big companies have big resources.” he says. “You need people who can cut through the company and use those resources… It’s a real entrepreneurial attitude.” Even so, there has been some jealousy directed towards the new-products group. Says Knight, “We have been getting a lot of criticism internally that [Strasser and his group] are the favorites. Well, they should be the favorites.”

Despite Strasser’s recent success, there are those who still find it hard to believe that this tyro survives. In addition to the mistakes Strasser has made over the years, there are a number of those at Nike who disdain his arrogant, anything goes attitude. For example, Bill Bowerman, the legendary University of Oregon track coach who founded Nike with Knight, is said to dislike Strasser. How then, has Strasser been able to last? The answer simply may be, as one former Strasser aide explained: Knight will keep him as long as he does his job “to keep the product fresh.”

Strasser’s response is to play down his role and instead emphasize what he says is the team effort. “Hey, there ain’t no heroes here,” he claims. “We’re just a bunch of guys who believe that excellence is everything — and that’s not just ’cause some turd wrote a book about it.”

Recipe for Success

The success, or for that matter the failure, of Nike cannot, of course, be attributed to one individual. In fact the Nike formula — while it has never been identified as such, there most certainly is one — contains a number of ingredients that together have catapulted a firm that 13 years ago had sales of under $2 million to one that today is verging on busting the billion- dollar mark.

• Production — It was Phil Knight’s genius to recognize that the success of his shoe company would be in its ability not to own and operate its manufacturing facilities. As a result, almost all Nike products are made by other firms — most of which are located in the Far East.

Part of the reason was that Knight didn’t want to spend the money on the bricks and mortar and equipment to build a manufacturing plant. But it also was that Knight knew that the single biggest cost in manufacturing shoes was labor and that by making the shoes in countries where labor costs are lower, he could control his dollars. As a result, a course in the industrialization of the Pacific Rim could be taught using Nike’s production history as a syllabus. At one point, most Nikes were manufactured in Japan, where labor costs were cheap and the technical know-how existed. But Japan’s economy grew, its standard of living increased, its labor costs rose — and Nike moved on. Today, the bulk of Nike shoes are manufactured in Korea. Tomorrow, it probably will be Thailand and China. The fact is, according to George Porter, the firm’s vice president of finance, “When people have the opportunity to make something other than shoes, that is probably what they will do.” Nike, he says “goes where the standard of living is low.”

• Financing — Back in 1971, Knight developed a relationship with the giant Japanese trading company Nissho Iwai, which agreed to lend money to the firm based upon the orders for shoes Nike had received. This is still an important relationship today, but it was even more so back when Nike was having difficulty finding financing. Then, shortly after the tie with Nissho Iwai was forged, Nike introduced its “Futures Program,” which was intended to give the American firm another financial edge and also to capitalize on a weakness of the number-one athletic shoe maker, Adidas. The Futures Program allowed major buyers to purchase shoes at a discount and with guaranteed delivery, as long as the order was taken sin months in advance Nike’s guaranteed delivery helped to undercut Adidas, which was notorious for being unable to deliver on time. Equally important, Nike could manufacture to order, so that it would reduce the risk of ending up with warehouses full of unsold shoes (Nike’s recent well-publicized inventory problems — it once had 22 million pairs of shoes on hand as opposed to the current 7 million was largely a result of the company not believing that its Futures orders were indicative of the slumping demand for shoes. Instead, it over-produced.)

Add a pinch of luck, a cup of competitor’s stupidity and a healthy dollop of good timing — you could not have given birth to an athletic shoe company at a better time — and you had almost all the ingredients for success. The other ingredient? " Remember what we are,” says Nike’s Porter. “A marketing company.”