This story first appeared in the Feb. 6, 1986, edition of WW.

Tom is a heroin addict.

He has been “strung out” since last summer. Before that he had been clean for almost two years. Then, he was a successful student at Portland State University, studying engineering and advanced mathematics. He was healthy, happy, and had a wonderful sense of humor. He talked endlessly of his regular fishing trips from the coast to the Deschutes.

Now. he looks tired, his eyes hollow, his face gaunt. His small apartment is filthy, cluttered with dirty dishes, overflowing ashtrays, and an assortment of junk-food wrappers. His clothes are rumpled and dirty.

Last Saturday, Tom was getting sick. He hadn’t had his daily “fix” of heroin. The withdrawal symptoms feared so much by all junkies had begun an hour or so before. His stomach was upset. His bones had begun to ache. He needed to score — quickly.

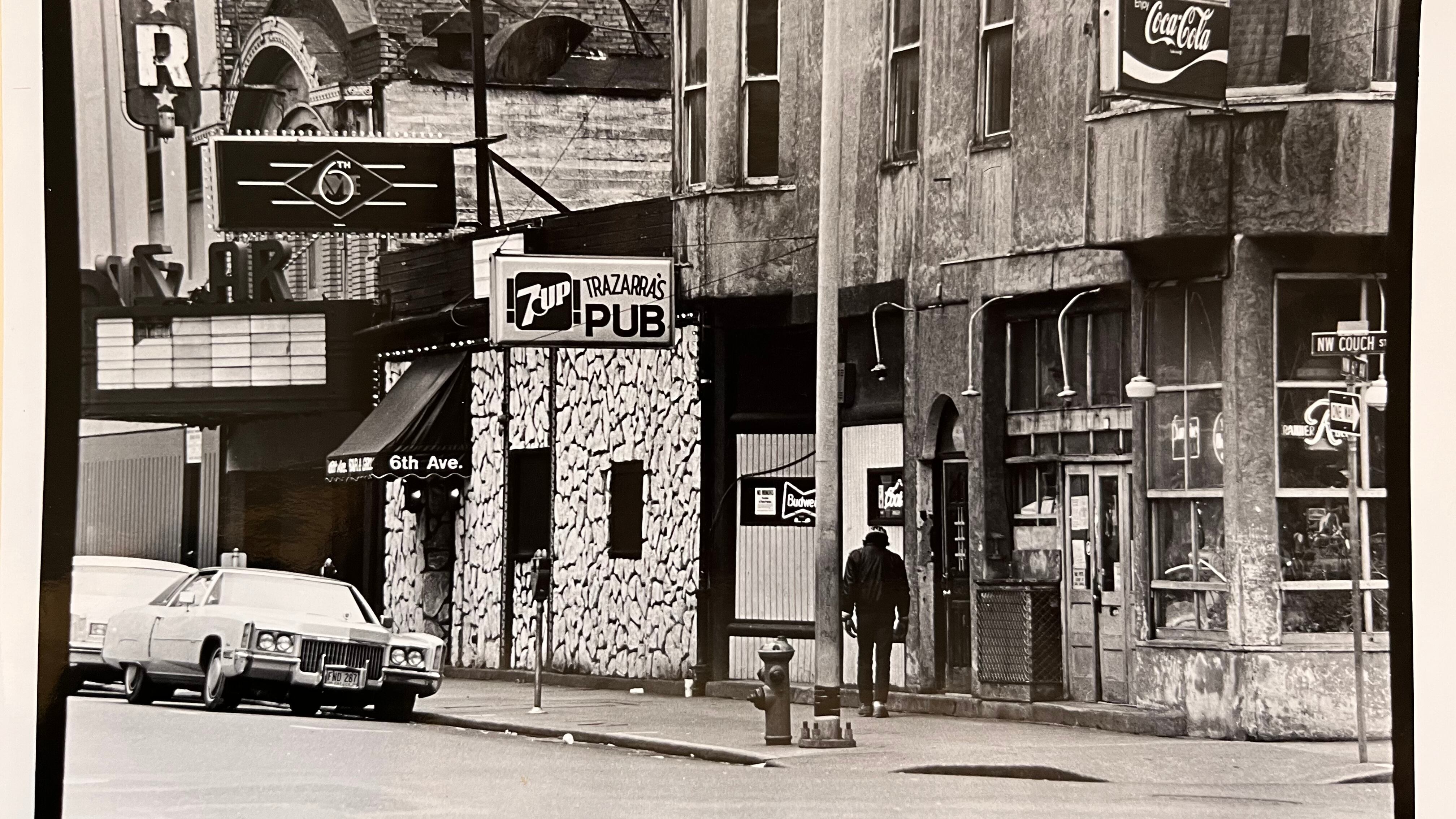

So, as he has done almost every day for the past three months, Tom headed to the Old Town area to find heroin He parked his car at the intersection of Northwest Couch Street and Broadway and walked toward Burnside Street, a block to the south. Before he reached Gordon’s 7 Up Bar and Cafe at 627 W Burnside St., Tom was approached by three different heroin dealers. Their sales pitch was to the point: “You lookin’, man? You lookin’?”

Inside the cafe, the competition was even greater. While walking to his booth and drinking a cup of coffee. Tom was approached four more times: “You lookin’, man? You lookin’?”

Just before he left, he stepped over to the booth in the back corner of the small cafe. He laid a $20 bill on the table and one of the three people in the booth, a Hispanic about 25 years old, laid a half dozen papers in front of him. Each paper contained an eighteenth of a gram (about the size of two paper matchheads) of Mexican tar heroin wrapped in cellophane. Tom took one and started for the door.

Suspicious of a man sitting at the coffee counter, Tom slipped the tiny packet in his mouth to be swallowed in case of trouble.

“You lookin’, man?” asked another dealer as he paid his check, and two others as he returned to his car.

Tom’s companion expressed amazement that so many people would be dealing heroin in one area at 10:30 on a Saturday morning. “That’s just a few of ’em,” he laughed “I saw at least six other guys in the cafe that I bought from before We’re early yet. If you really want to see ‘em, come down between noon and 10 at night.”

As he turned west on Burnside. another Hispanic in front of the Burger King recognized Tom and shouted, “You lookin’, man? You lookin’?”

He smiled at his companion. “Welcome to heroin alley.”

John’s 15-minute shopping trip graphically illustrates a development in Portland about which there is little debate. Everyone, from local narcotics investigators, to drug rehabilitation counselors, to the emergency medical personnel who have been treating hundreds of overdose victims, agrees that the heroin business in Portland is booming like never before.

Why is Portland fast becoming the heroin capital of the West Coast? That is a question which has no single answer. There is, in fact, an increasing amount of heroin making its way into this country, partly because the Reagan administration, despite its much vaunted war on drugs, has reduced the number of customs agents at the border with Mexico. But Portland seems to be receiving a larger proportion of heroin than the population would seem to warrant. Some officials contend that Oregon’s lax laws regarding the purchase and possession of paraphernalia used to inject heroin are a factor. Others contend that the lack of jail space has become well known all over the West Coast, thus converting Portland into a magnet for heroin dealers who know that, even if they are apprehended, they will serve little if any time.

But in addition, many members of the region’s narcotics enforcement community, including most of the Portland Police Bureau’s officers, are pointing accusing fingers at Police Chief Penny Harrington for her reorganization of the bureau’s drugs and vice division. Critics say that the reorganization, which began shortly alter Harrington took office a year ago, left the department almost totally unable to contribute to regional efforts aimed at combating the heroin trade that has reached such astronomical levels today.

“Portland is bulging at the seams with heroin,”according to a western United Stales heroin industry study prepared last August for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. The report suggested that “Oregon will soon be leading the nation in the number of narcotics users and dealers…”

Developments in the months since the study support that prediction. Tom says that prior to last fall he had to look a little to find a regular source, but since then a smorgasbord of drugs and dealers can be found all over the Old Town area. He claims he could buy heroin almost any time of the day or night at the Old Town Cafe, Trazarra’s Pub, the Broadway Cafe, the Stewart Motel and almost any street corner in the area. “There are three times as many dealers working Old Town than I have ever seen prostitutes on Union Avenue,” says Tom. “I would guess there are 50 different dealers doing business during the evening hours.” The vast supply has left Portland with the cheapest heroin available on the West Coast. Sgt. John Bunnell, head of the narcotics unit of the Multnomah County Sheriffs Office, says the price of a gram here is between $220 and $230. which is less than the going rate in Los Angeles and a little more than half of the $400 price paid in Seattle. (A junkie needs anywhere from $20 to $200 worth a day to avoid getting sick.) Bunnell also notes that the price in Portland was $445 a gram less than a year ago. “I have worked drugs since 1977 and I have never seen the availability of heroin anywhere near today’s levels.” he says. “The price is just an indication of the magnitude of the problem.”

The black tar heroin appearing in such quantity on the streets of Portland is a relatively new product in the international heroin trade, according to DEA regional spokesman Robert Dreisbach, who is stationed in Seattle. “Prior to 1980, we saw only a brown powdered form of heroin from Mexico and a white powder that originated in Southeast Asia and had become popular with Vietnam veterans.”

Dreisbach says the DEA began hearing occasional reports of tar heroin, then called “Mexican mud” because of its gummy texture, sometime in 1980. “We didn’t pay much attention to it until ”82 or ’83,” he says, “when we began seeing more and more of it and the lab tests we ran showed the purity of it to be in the 50-60 percent range. The powders had only been about 3-5 percent.”

Dreisbach says that most of the tar heroin, which he says often is smuggled into the United States by undocumented workers, originates in the central Mexican states of Michoacan and Sinaloa. “We are finding that 15 to 20 families control the supply coming into the U.S.,” he says, adding, “Two years ago, tar was not seen much in Southern California, but was brought directly to the Northwest where it became the heroin of choice Iately. it has become more popular in many other parts of the country.”

After his purchase of heroin last week, Tom drove to the Fred Meyer store at 20th and West Burnside. He proceeded to the restroom outside Eve’s Buffet Restaurant. He look a teaspoon from his pocket and half filled it with warm tapwater. He placed the heroin packet in the water for a couple of seconds until it warmed slightly, then tore the tiny cellophane wrapper and slipped the heroin back into the water. He then went into the only toilet stall in the small restroom and placed the spoon on the toilet tissue dispenser. He removed a full pack of paper matches from his pocket and lit the entire book at once He held his homemade torch under the spoon, moving it back and forth until the water came to a boil, dissolving the heroin.

Next, he took a handkerchief out of the pocket on his coat sleeve. Inside was a syringe. (“They are U-40 insulin syringes. You can’t buy them in California without a prescription; almost anybody sells them to you here.”) Tom stuck the end of the five-eighths-inch needle into the solution and drew it out of the spoon. He made a fist with his left hand and squeezed it repeatedly as if he had a rubber ball in it. In about 10 seconds, he slowly injected the needle into the inside of his left arm just above the bend in the elbow Another 15 seconds later, he had injected the entire solution. He got up tossed the syringe into a trash can. put his spoon back into his pocket and headed for the door.

“Aaahh,” he sighed as he left. “That feels a lot better. Maybe I’ll kick tomorrow. "

The numbers of junkies being found dead or nearly dead from overdoses in restrooms, homes, and street corners all over the city is another indication of how heroin use has increased in Portland. In 1984, 23 people in Oregon died from overdoses involving heroin, and in 1985, 57 fatal overdoses were recorded, according to Multnomah County Medical Examiner Larry Lewman. Lewman says the majority of the deaths occurred in Portland and involved longtime heroin users, mostly males between the ages of 25 and 35. Lewman noted that the number of heroin-related deaths has risen sharply in the last four months, with 19 occurring between October and December and another three during the first two weeks of January.

Lewman adds that last week he was told by Tom Locke, an FBI agent from Washington, D.C., who is conducting a national survey of the tar heroin situation, that Portland had the highest per capita rate of deaths due to heroin overdose in the entire country.

In addition to the fatal overdoses, area ambulance companies report that they have been responding to a very high number of overdose calls. When a person overdoses on heroin, he stops breathing and can die in minutes if not treated. Injections with the drug Narcan almost instantly negates the effect of the heroin; emergency medical personnel from the city’s ambulance services say they have had to use the treatment on hundreds of overdose victims in recent weeks.

Alec Jensen of Buck Ambulance, which serves the downtown and inner east-side area, says, “Overdose calls were exceedingly high throughout December and into January. Our two units responded to two or three overdose calls almost every day.”

Jensen says the victims are found throughout Buck’s service area. “They seem to head for the nearest bathroom after they get their stuff,” he says. “We have picked up people in bathrooms from the Shell station at 12th and Southeast Hawthorne, the Stewart Hotel and the Burger King at Broadway and Burnside, even one guy at the Hilton. Most are indigent, but probably 3O percent are employed. We hauled a guy in a three-piece suit out of one of the cheapest hotels in Portland.”

Representatives of AA and Care ambulance services, which cover the north, northeast, and central east-side areas, report similar increases in overdose calls.

Drug treatment centers also are receiving an increase in inquiries regarding heroin addiction. Doug Cross, clinical supervisor of the Alcohol and Chemical Dependency Program at St Vincent Hospital, says, “We got only about one or two calls a month regarding heroin until November of last year, when they started coming in at a rate of three or four a week.”

HEROIN’S COTTAGE INDUSTRY OF CRIME

To avoid getting sick, junkies need more heroin. To get the heroin, they need money. Sometimes lots of it. Obviously there are a limited number of ways for unemployed drug addicts to come up with upwards of $100 or $200 a day. Burglary, robbery, shoplifting, forgery, drug dealing, and prostitution are the most popular.

“They will do anything they have to to satisfy their habit,” says Multnomah County Circuit Court judge Richard Unis, who has sentenced hundreds of addicts on a variety of charges over the years.

“Not all burglars are drug addicts, but most drug addicts are burglars or into some kind of theft,” says Dr. Jerry Larsen, one of the leading experts on heroin treatment in the country. Larsen has counseled thousands of addicts, many at CODA, a treatment facility at 306 NE 20th Avenue where junkies are often given the drug methadone to avoid “getting sick” while withdrawing from heroin.

Usually addicts must steal goods worth $600, $800 or more in order to sell it to buy $100 worth of heroin, according to Portland Police Officer Ed Cummings, who patrols the Old Town area. Cummings says stolen property is either sold lo a fence or traded directly for drugs. He notes that he has seen several known fences frequenting the Old Town area since the heroin trade has increased there. He also notes that among them are two known fences from other parts of the state who apparently migrated to the fertile ground provided by the increased traffic in stolen property.

“Boosting” is a specialized form of theft which often allows addicts a dollar-for-dollar return on their stolen goods. It involves shoplifting goods from department stores, often in malls, and returning them for cash refunds. Sometimes addicts work alone, but often, one person does the shoplifting and another handles the returning. Profits are divided equally or the returner sometimes gets a smaller share.

“I am the ace returner,” says Tom. “I have been doing a lot of returns for a married couple (who are also addicts) with a kid,” he adds. “I got $250 in an hour and a half the other day. “They usually get $200-$300 a day working Frederick & Nelson, Nordstrom, and Meier & Frank, Once you get your rap down, it’s a piece of cake. After Christmas we had a field day.”

Ted Hodges, Frederick & Nelson vice president, says he knows his company’s stores are continually being ripped off by junkies. “Our security people regularly find drug paraphernalia, including syringes, on people they catch shoplifting,” he says.

“Although apparel is the most popular item.” Hodges adds, “they will steal anything they can get their hands on, from television sets to girdles filled with all kinds of goods.”

Still, Hodges says, proper service to regular customers requires that Frederick & Nelson maintain its policy of offering cash refunds to anyone returning merchandise, even without a receipt. Others, such as Fred Meyer, limit the number of times any one person can ask for cash returns.

Increased drug use often leads into the drug dealing business. Tom estimates that 95 percent of the people who deal heroin on the street are users and sell partly to support their own habits. Sgt. Bunnell of the sheriff’s office is more conservative, setting the number at 60 percent.

Susan Hunter, who counsels current and former prostitutes at the Council for Prostitution Alternatives, says a large number of the women she works with turned to prostitution to support heroin habits, and earn “usually around $100 a day.” Hunter also notes, “After a bad day or when they are pregnant, such addicts move into theft and lower-class forgery involving such things as food stamps and welfare checks.”

Although both Tom and CODA’s Larsen say heroin addicts are not usually violent, others, such as Judge Unis, disagree. “We are seeing more and more violence.” Unis says. “Pre-sentence reports show that many heroin users are also armed robbers.”

Dennis Fitz worked on homicide cases for five years at the Multnomah County Sheriff’s Office before recently transferring to the narcotics unit. “I would say that 60 to 70 percent of the murders I investigated were drug-related,” says Fitz, although many did not specifically involve heroin.

Mid- to upper-level heroin dealers almost always are armed, according to police, who often find weapons when serving search warrants. At a recent Washington County trial of three men arrested in connection with a large heroin and cocaine bust near Banks last November. several weapons, including a .357-caliber Magnum and .45-caliber pistols as well as an Uzi “machine pistol.” were introduced as evidence.

Such weapons may be used primarily to intimidate prospective drug thieves, but they are not just for show. On Jan. 5, two men identified by junkies and narcotics officers as prominent Old Town heroin dealers engaged in a shoot-out inside the Old Town Cafe, 32 NW Third Ave. Several rounds of .45-caliber pistol fire in the small cafe left one man, Ramon Lopez, dead from multiple gunshot wounds.

JAIL SPACE

II heroin spawns such a vast array of other problems, how has it been allowed to grow to the extent it has in Portland, especially during the past year? Seattle has a problem. So do Los Angeles and several other major cities, but nowhere has the heroin outbreak been as significant as in Portland during the last year. Why?

Dr. Larsen, Judge Unis, Chief Harrington, Mayor Bud Clark, county prosecutors, and narcotics officers all agree that the lack of jail space makes their respective roles in combating the heroin problem very difficult, if not impossible.

Because the jail at the Justice Center is so overcrowded, people caught dealing or possessing small amounts of heroin, or committing burglary or shoplifting to support their habits, rarely spend more than a few hours in jail, if any time at all. Deputy Police Chief Robert Tobin says, “Sometimes when we arrest a street dealer holding money and drugs, the people at the jail radio us that they are full and we have to write them a citation to appear in court on the charges. They are back dealing drugs almost as soon as the patrol car is out of sight.”

The situation at the Oregon State Penitentiary in Salem, where larger dealers or those with repeated convictions are housed, is even worse. Multnomah County Deputy District Attorney Charles Ball described what convicted drug dealers face: “The first conviction usually gets probation and direction to a treatment center. The second, maybe some local (Justice Center) jail time. The third or fourth conviction might end up with some time at the penitentiary, but some still get only probation and local time. Even if a guy is sentenced to, say, five years at Salem, chances are that he will be out in six months.”

Hall said that lately some defendants even prefer to get longer penitentiary sentences than shorter local penalties because the overcrowding in Salem often means they still get out sooner than they would if they went to the county jail.

Because many major drug arrests are made as a result of apprehended smaller dealers giving police the names of larger dealers in exchange for plea bargains or reductions in jail time, the police lose a valuable investigative tool under the current situation. Lt. Chuck Karl, who now heads the narcotics unit of the Portland Police Bureau, says, “I recently approached a convicted dealer about trading us some information for jail time and he just laughed at me.”

Not just people in the law-enforcement community point to the jail-space dilemma as a contributing factor to the heroin situation.” Drug addicts do not seek help until they are threatened by an outside force,” says Larsen of CODA. “That force can be any number of things, from the threat of losing a job or family, but jail is one of the most effective I have seen. The law is not a deterrent at all, but sentencing is most definitely a deterrent.”

Even with the jail-space problem, area law enforcement officials say some effective tools exist to penalize drug dealers and fight the growing heroin trade.

In addition to similar state and federal laws, Multnomah County and the city of Portland have been using a forfeiture ordinance under which assets seized from convicted drug dealers can be confiscated by the authorities. “What we try to do at the sheriff’s office is hurt dealers by taking their money, then using that money to hurt more dealers.” says Multnomah County Counsel Noelle Billups.

“The county forfeiture ordinance is the best thing we have going now,” says prosecutor Ball.

Ball also says a cooperative effort between local prosecutors and the U.S. Attorney’s Office to prosecute heroin dealers in federal rather than state courts is being expanded. People caught dealing heroin can be prosecuted in either state or federal courts, according to Ball; the difference is that the federal laws and penalties are stronger and the federal penal system has space available. Under the expanded cooperative effort, local prosecutors would be cross-designated as special prosecutors for the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

GUTTING A DEPARTMENT

Obviously, before drug dealers can be sent to federal prison and forfeit their drug-related assets, they have to be arrested. Unfortunately, at a time when the number of heroin dealers and users in Portland was on the rise, the Portland Police Bureau’s arrests of significant drug dealers were virtually non-existent.

Prior to Penny Harrington’s appointment as chief in January 1985, the drugs and vice division (DVD) had, by many accounts, recovered from the scandals that had rocked the division three years earlier, and was functioning as a very effective unit.

One former member of the DVD, who requested anonymity, describes the old unit. “We were making pound busts on a regular basis and had helped create a sense of paranoia among top dealers,” he says. “I know it was getting so hot that one of our major dealers was leaving town for Seattle. We had experienced guys who worked great together as teams and had lots of good informants.”

Last April, four months after she assumed office, Harrington — over widespread objections that the move would have tremendous adverse effects — disbanded the DVD. All but two of the longtime drug investigators from the DVD were assigned to other duties. Eight other members of the detective division were assigned to drugs. Overall, the number of Police Bureau employees working on narcotics was reduced by four.

Harrington says she was trying to accomplish two things when she disbanded the DVD. First, she wanted to put drug enforcement in the detective division to bring about better coordination between often-related burglary and drug investigations. Second, she had to contend with severe budget cuts, yet she wanted both to increase the number of patrol personnel and launch a juvenile enforcement program.

Part of the morale problem Harrington is faced with in the Police Bureau is due to the strong sentiment on the part of some rank-and-file officers that the department’s shift in emphasis from narcotics to juvenile offenses such as curfew violations and truancy (16 juvenile officers have been added to an existing force of 16) has been a mistake. “Somebody’s priorities are a little screwed up if we have 32 officers playing mom to 16-year-old kids and only a dozen cops working drugs, especially when the situation has gotten as bad as it is now,” says a former DVD officer.

More important than the reduction in numbers has been the replacement of experienced investigators with those totally lacking in the special skills needed to battle the narcotics trade. Writing search warrants, preparing affidavits for the use of electronic listening devices, operating sophisticated equipment, developing key informants, following money trails, learning the particular jargon of the drug world, establishing relationships with officers of the other law-enforcement agencies involved in stemming the drug trade, are only some of the areas where officers need expertise. The learning curve in the business is a long one, according to Tobin. “It takes a certain type of individual to make it and probably two years to become fully trained in all the areas necessary.…We have made some mistakes and not going more slowly with the reorganization was a biggie.”

Arrest reports provided by the bureau show a 70 percent drop in the number of arrests for narcotics in the first six months after the DVD was disbanded, compared with the six months prior to Harrington’s actions. The decrease in arrests is even more startling, considering that it occurred at a time when drug traffic, especially in heroin, was skyrocketing, according to a wide variety of sources.

Another index of the effectiveness of the bureau in combating narcotics has been the use of the forfeiture law, which allows police to seize assets of dealers. During the last four months that the DVD was in full operation, the bureau seized some $95,000 in cash In the 11-month period since last February, when former DVD members say they were instructed to wind down their efforts before the actual disbanding of the division in April, only $14,000 has been seized.

“The reorganization utterly gutted the narcotics division,” says Hall, who heads the unit in charge of prosecuting drug cases. “All of a sudden, nothing was coming out of the new division, except a few chippy little cases. The quality of the work went way down.”

For her part, Harrington defends her decision to radically transform the narcotics team and remains convinced that over time, it will prove to be a prudent decision. “Do you chop off an arm an inch at a time or all at once?” she asks rhetorically. At the same time. Harrington plans to ask for money to hire four more narcotics detectives. In addition, she has named Lt. Karl, who had worked for DVD and was transferred to personnel as a result of Harrington’s shuttle, as supervisor of the new narcotics unit.

A number of officers in the department hold much the same view. “As the experience (of the new drug unit) increases, we are starting to see improvement,” says Tobin. None of the new members of the narcotics team was willing to speak on the record.

Harrington’s move eventually may prove to be the correct one. In the meantime, however, the city faces an epidemic of heroin abuse the likes of which it has never faced before. The most critical in the bureau point out that one of Bud Clark’s chief campaign promises was to reduce the amount of burglary in the city. In fact, that burglary rate continues to grow, and one officer, who asked not to be named, had an explanation: “How can anyone expect the burglary rate to go down when Portland is becoming a magnet for heroin junkies?”