Want to check if somebody has lived in Portland for more than 20 years? Say the words “Macheezmo Mouse” and see if their eyes glaze over in reverie. Portland industrial heir Tiger Warren’s concept was ahead of its time: a burrito joint with ingredients as healthy as the service was swift. Today, we call that dining sector “fast casual” or just “Chipotle.” But in the 1980, it was unusual—and in the ‘90s, its stock began to tumble.

As another Oregon-founded company, Chalice Brands, is now watching its stock become worthless, we travel back to the moment when the peril facing the Mouse first became clear. Three years after this story ran, tragedy struck: The seaplane Warren was piloting crashed into the Columbia River on Nov. 28, 1999, killing him and his three young sons.

This story first appeared in the Aug. 7, 1996, edition of WW under the headline “Mouse Trapped.”

The receptionist at Pacific Crest Securities, a Seattle-based research firm that watches stocks for Wall Street investors, was surprised to hear the words “Macheezmo Mouse.” “Oh!?…We don’t get many calls on the Mouse these days.”

Indeed, these days most investors aren’t too interested in the stock of Portland’s once-beloved and quirky Mexican restaurant chain, which tumbled to an all-time low of $1.85 per share in June. (In 1994, the stock commanded $11.25 per share.) This is the very same company that just two years ago went public with sizzling market numbers, the same hip and healthful restaurant that brought us “clean calories” and earned a mention in Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho, the same unique local start-up that blazed into national prominence with buzz from The New York Times, Newsweek and The Oprah Winfrey Show.

These days, the buzz isn’t so good. Macheezmo’s shareholders are concerned. What’s wrong with the Mouse? Is it founder and CEO Tiger Warren’s messy private life? Macheezmo’s inattention to price wars? Or is it simply that Macheezmo’s very raison d’etre—healthful fast food—isn’t the sort of cuisine that can hook a national market?

Whatever the reason, this summer—when Macheezmo’s third-quarter report showed a loss of $317,000—the company faced reality and closed three stores. In May, two of its seven board members resigned, and in June, Macheezmo president Rex Bird left.

In the past few months, Warren has been quietly but forcefully beefing up his board of directors with industry bigwigs David Bennett, who was a Taco Bell executive for eight years, and Joseph Micatrotto, an industry all-star who took Chi-Chi’s from a 26-store chain to a 265-store chain during his tenure as CEO in the 1980s.

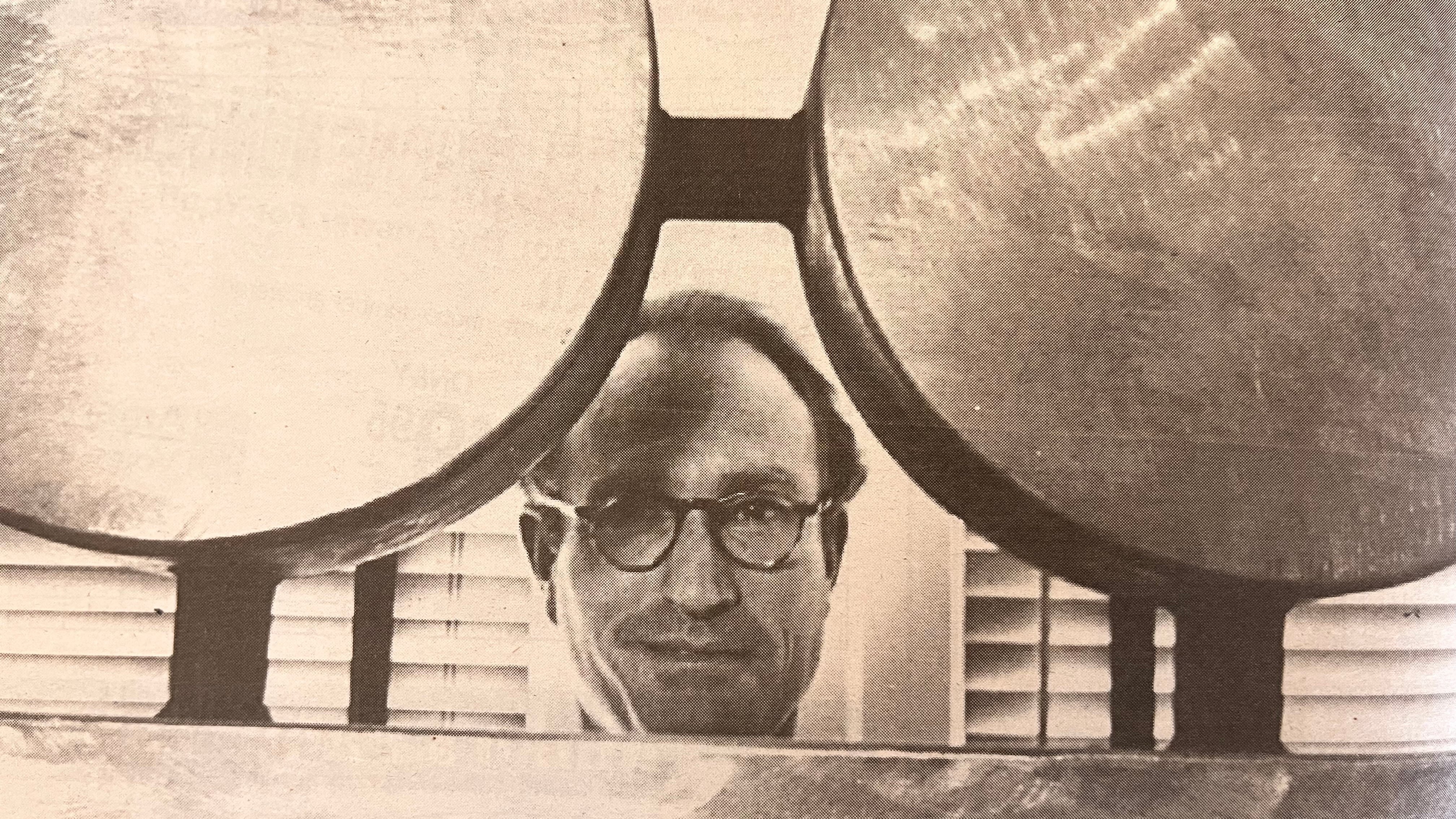

Warren, meandering around his desk gesticulating and cursing, says he wants to ensure that his company can eventually succeed in the nation’s major markets by appealing to a more mainstream diner. But for those of us who have become addicted to Macheezmo’s low-fat jack cheese and preservative-free chicken, here’s the question: Can Warren sell the Mouse to a mass audience without losing the unique concept that made it work in the first place?

In 1981, Warren, a 29-year-old filmmaker and heir to one of Portland’s larger industrial fortunes, found himself “patently unhireable.” His motley résumé credited him with producing a handful of Yamaha motorcycle commercials, producing an obscure 1977 MGM film called Skateboard and receiving a liberal arts education at Franklin College.

Warren, whose filmmaking career and first marriage were—in his own words—”really fucked up,” became friends with legendary Portland restaurateur Michael Vidor, eccentric Harvard graduate and onetime owner of Tanuki, Warren’s favorite evening haunt at the time. Over drinks one night at the Southeast Portland Japanese restaurant. Warren asked a fateful question: “Michael, what’s a smart guy like you doing in a stupid business like this?” Vidor replied: “If you’re so smart, you come up with an idea for a restaurant.”

Warren did a little research and found that Portland restaurateurs were missing out on the untapped market between fast food and fancy dining. Taking 51 percent in a partnership with Vidor, Warren in 1981 invested $18,000 in a small storefront space on Southeast Milwaukie Avenue and started a restaurant featuring half-chickens, rice, beans and salsa, called Macheesmo Mouse (then spelled with an s)—a goofy yet strangely catchy name Vidor had suggested in desperation one night after a lubricated brainstorming session.

Within a year. Warren started fashioning the space into an edgy, off-beat attraction of corrugated metal, New Wave colors and health-conscious food. He bought out Vidor in 1984. The store began to introduce healthful items and list calorie counts on its menu board, inspired in part by the cooking genius of Diane Hall, who is now Macheezmo’s vice president of marketing and research.

Macheezmo lost money in its first few years. Then, around 1985, the preservative-free chicken and nonhydrogenated-vegetable-oil cooking standards began appealing to the taste buds of newly health-conscious Portlanders. Warren says he just “rode the trend.”

Between 1984 and 1994, the Mouse expanded from a two-store Southeast Portland outfit to a 16-store chain with restaurants from Beaverton to Seattle. Macheezmo went public in September 1994, raising $6 million in a notably hot public offering. The company opened six more stores in ‘95 for a total of 22 outlets.

Warren says he always knew he wanted to be a businessman, but he also knew he wanted to start his own company. “It became apparent to me at a young age that I didn’t want to get involved in the family companies,” he says.

Warren’s family tree reads like a who’s who of the Portland business elite. William Swigert Warren (aka Tiger) is the great-grandson of Charles Swigert, a prominent turn-of-the-century Portland businessman who, among other things, headed the Port of Portland, served on the Chamber of Commerce, built the Morrison Bridge and, with his son Ernest, laid the groundwork for two phenomenally successful Oregon manufacturing companies, ESCO and Hyster. Hyster was sold in the mid-1980s, and Ernest Swigert’s grandchildren—Tiger Warren among them—inherited $4 million to $5 million each.

Warren, who has a penchant for driving flashy cars and collecting private planes, reveled in the good life. He and his second wife. Gerry Pope—of the Pope & Talbot lumber fortune—were known for throwing gigantic parties at the Warren compound in Prindle, Wash.

“She was an amazing host,” one frequent attendee says. “She set up elaborate decorations, and she had an amazing wardrobe,” including an extensive collection of leather suits.

Warren was also part of the atmosphere. “Tiger drinks and he’s a major flirt,” a friend of Pope says.

A slightly disheveled and boyishly handsome Warren, wearing a bright red tie straight out of a Devo video, laughs about his reputation. “I’ve never been able to figure it out. I’m news in Portland, Oregon. People have this perception that I’m really wild and crazy and there’s 14 bimbos back in my office.

“I wish I could say I’ve had as much fun as people like to think,” he concludes, “but it’s not true.”

Warren says he simply loves to “live life” and “take risks.”

Unfortunately for Warren, by expanding his chain too quickly he might have put the success of his business at risk.

Fiscal 1996—a year Warren had once slated for greater expansion in Oregon, Washington and beyond—was a fiasco. Not only did Warren fail to open any new restaurants, he closed three. Alarmingly, in the first nine months of fiscal ’96 the company lost $887,000 on revenues of $10 million. (The year-end report is due out this month and is not expected to look good.)

“They went to hell in a hand basket,” says new board member Bennett.

What went wrong? People in the restaurant industry agree that Macheezmo had a great initial concept: healthful food in a quick-service environment. “When they started, they had a niche that was very unique,” says Howie Schecter, co-owner of Portland’s Chez Jose restaurants. “They had a classy, hip interior with an inexpensive healthful burrito.”

“[Warren] came up with a great concept and perfect timing,” says Greg McGrew, a local restaurant consultant with Hospitality Profit Builders. “It was a non-mainstream concept that was about to break. He was ahead of that curve.”

Industrywide, the overwhelming consensus is that Warren—who owns 36 percent of the company’s stock, valued at roughly $3.5 million—is a talented, creative, charismatic visionary.

At the same time, observers say that Warren himself is part of the company’s problem. Longtime friends of the Swigerts and Warrens say they think Warren’s freewheeling lifestyle tripped up his business savvy.

In 1994, Warren went through an extremely bitter divorce from Pope, an event that even Warren concedes had a major impact on Macheezmo Mouse. “The divorce took its toll,” he says. “I blew the opportunity a little bit. I wasn’t able to take enough of a leadership role.”

Some industry analysts, such as Alan Liddle, the West Coast editor of Nation’s Restaurant News, aren’t interested in Warren’s personal life and instead blame the Mouse’s inattention to competitive pricing. “Taco Bell has driven price expectations for Mexican food down,” Liddle says. “If you’re making a fast-food decision and you’ve got 50 cents in your pocket, where are you going to go?” Macheezmo’s prices range between $3.25 and $6.

“In the arena Warren’s in,” restaurant consultant McGrew says, “price is what brings you back. I’ve perceived a reluctance on their part to get into discount marketing. Boss sauce is fine,” he says, referring to Macheezmo’s signature sauce, “but Taco Bell is two-for-one.”

Though Macheezmo’s prices or Warren’s divorce might be partly responsible for the company’s recent misfortunes, analysts overwhelmingly point to another fundamental factor in the Macheezmo profile: They say the company’s choice to attach itself so closely to the image of “healthy” food—it’s in Macheezmo’s slogan and storefront logo—is at direct odds with consumer trends.

Given the increasing health consciousness of Americans, this may strike many as odd. In fact, vitamin giant GNC’s recent purchase of Nature’s Fresh Northwest seems to provide evidence of the growing health-food market. But a number of restaurant owners and industry analysts say that the public is fickle. Consumers “shop healthy” at the grocery store, but when they eat out, they lust for fatty foods.

After all, 1996 is the year that McDonald’s, the surest barometer of the market with 11,000 stores nationwide, shelved its low-fat McLean Deluxe because sales were dismal, replacing it with the bacon-laden Arch Deluxe. “People just didn’t buy it,” says Louise Kramer, senior editor at Nation’s Restaurant News. “Americans must be lying about eating healthy when they’re surveyed, because sales numbers definitely show they go out for bigger, juicier, fattening foods. We want the fries and the cheese.”

Recently, Taco Bell, the largest fast-food Mexican chain in the country, scrapped Border Lites, its alternative health-conscious menu, which it introduced just last year. Kramer called Taco Bell’s campaign to hawk healthful Mexican “a total bomb.” Taco Bell spokeswoman Laurie Gannon says, “Our core customers are demanding more indulgent variety options, like the bacon items and the double-decker tacos.”

Taco Bell customers aren’t the only ones looking for fatty foods. Pizza Hut and Jack-in-the-Box, for example, have had renewed sales success with cheese-stuffed crusts, juicier, messier, bigger burgers and milkshakes made with real ice cream. Meanwhile, the “Double Drippers” ad campaign at Carl’s Jr., which tells consumers that “If it doesn’t get all over the place, it doesn’t belong in your face,” has boosted the California-based chain’s once-sagging sales and stock value.

“[Health] just doesn’t appeal to people day-in day-out for the kind of traffic a fast-food business plan needs,” says Nation’s Restaurant News’ Liddle. He says healthful meals have become special occasions for many people. “I’d be hard pressed to name a successful ‘healthful’ restaurant chain.”

With the divorce behind him, a new girlfriend and a new house (he recently bought former Trail Blazer and L.A. Lakers forward Mychal Thompson’s home in Dunthorpe), Warren says the Mouse is ready to roar again. And though he doesn’t plan to lower Macheezmo’s prices, he will address the concern that Macheezmo is too “healthy.”

Warren candidly concedes that Macheezmo’s obsession with calorie counts and healthful food became “frumpy” and “boring.” Macheezmo, he says, was part of “neo-prohibitionist era, taking ourselves too seriously.”

“We positioned ourselves around health, and now we need to back away,” he says. “We looked at our menu like it was the Holy Grail, but we need a broader flavor profile.”

Upcoming changes include scrapping the “Healthy Mexican Food” logo that currently adorns every Maeheezmo storefront, adding entrees like steak fajitas and the Lone Star Wrap (“a big, meaty man-handler with real sour cream”) and nixing the calorie-count menu boards.

“Our entrees can be healthy or not-so-healthy,” Warren says. “Customers want that choice, and we have to appeal to mainstream demographics. The menu needs to be taste-driven. and if something tastes absolutely great and it doesn’t meet our current health criteria, that could be OK.

“We’re not going to come out with a cheeseburger, but we could come out with a steak burrito,” he concludes. “I want that blue-collar guy in Tacoma to get off his shift and come into Macheezmo and say, I want a steak burrito, and don’t give me any back talk.’”

As the plans unfold, Macheezmo’s staff has been placed in the awkward position of talking directly to customers about the changes. “No more calorie counts on the menus?” a bewildered customer complained on a recent Thursday night at the Hawthorne-area Macheezmo. Turning to her friend, she said. “Man, they used to list all the calories. Macheezmo is slipping.”

“I’m into low-fat,” Holladay Market Macheezmo supervisor David Bailey says, “but it doesn’t have to be the old idea of healthy—made out of granola and sawdust to be healthy. We’re going to expand people’s palates.” Like most of the spunky Macheezmo workers. Bailey (who owns 50 shares in the company) says he’s excited about the changes.

Pushing the turnaround is new board member and former Taco Bell exec Bennett, who says Macheezmo’s plans to expand are targeted at the single male market that goes out after work for so-called “replacement meals.” That male market is growing and seems to be more concerned about flavor than health.

“We’re getting out of the healthy market,” Bennett says. “If the Mouse was going to stay a 10- to 20-unit chain with that narrow niche, they probably could, but the fact of the matter is there’s much more opportunity to appeal to a broader market.”

Bennett says Warren approached him in March about joining Macheezmo’s board. Bennett told Warren he would only join under certain conditions. “Let’s just say everything that has happened since then were the conditions,” Bennett says, alluding to the June 4 departure of Macheezmo president Rex Bird, the resignation of former board members Timothy Bliss and Maurice J. Duca, the move away from a “healthful” menu and the addition of former Chi-Chi’s exec Micatrotto (Bennett’s close friend) to the board. Bennett says the board hopes to hire a new president by the end of this month.

Bill Whitlow, a stock analyst at Seattle’s Pacific Crest Securities, and the only analyst in the country still officially following the Mouse, is confident about Warren’s recent moves. “The worst is over,” Whitlow says. “As fiscal ’97 unfolds, the numbers are going to look good.” Whitlow says Macheezmo has a strong balance sheet with a lot of money in the bank and no debt to speak of.

“The stock is already picking up,” Whitlow says, “because the market is always looking as far forward as it can, and we see major improvement in fiscal ‘97.” (At press time. Macheezmo’s per-share price was $2.75.) Whitlow says the market isn’t concerned about Macheezmo’s year-end report because everyone already knows it’s going to be bad news.

Other market analysts aren’t so sure. Dominic Marshall, an analyst at Portland’s Red Chip Review, who recently stopped following Macheezmo—and gave it a thumbs-down to investors interested in growth stocks—says it’s important to note that Macheezmo Mouse has no track record of making a turnaround. “They came out hot, and that’s it.” Michael McCullum of the Oregon Restaurant Association says he wonders if Macheezmo’s turnaround plans will jeopardize the very qualities that catapulted the Mouse to its initial success. “The less mainstream a concept,” he says, “the harder it is to duplicate when you attempt expansion.”

Macheezmo’s new strategy officially started in July with an ad campaign directed at industry giant Taco Bell; a full-page color promo in The Oregonian blared, “For Whom the Taco Bell Doesn’t Toll.” Macheezmo’s battle with the big boys, however, could be rough going. The ad had appeared only once when the daily decided not to run any future installments, telling Warren’s designers at Cole & Weber that it was canceled because it denigrated other products.

“You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to figure out that Pepsi-Co [which owns Taco Bell] is a huge corporate advertiser,” Warren says. “Pepsi waved a big stick and The Oregonian listened.”

The Oregonian declined to comment on the nixed ad.

With the addition of its own corporate bad boys, however, Macheezmo’s board is hardly intimidated by the coming battle. “I wouldn’t put my reputation and years of experience in the restaurant industry on the line,” Bennett says, “if I wasn’t very confident in the Mouse.”