When you imagine the riot squad charging, batons raised, into a throng of black-clad anarchists, scattering them across downtown Portland, what year is it? 2020, as rioters surround the courthouses? 2016, after Trump’s election? Maybe 2011, when Occupy Portland wore out its welcome? In fact, similar scenes date back well into the 20th century. One of the uglier clashes—in which a new police chief from L.A. made his presence felt with beatings and beanbags—occurred on May Day of 2000.

This story originally ran in the May 10, 2000, edition of WW, under the headline “The New Portland Police Bureau.”

During the last week of April, Portland police began to hear that things could get ugly on May 1.

May Day is the international holiday commemorating the Haymarket Square riot of 1886 that symbolizes the struggle for workers’ rights. The police knew that a legion of labor organizers, here for the ILWU national conference, would use the anniversary to demonstrate against Powell’s City of Books. But they also received reports that some of the anarchists blamed for the mayhem during the WTO demonstrations in Seattle were also coming to Portland.

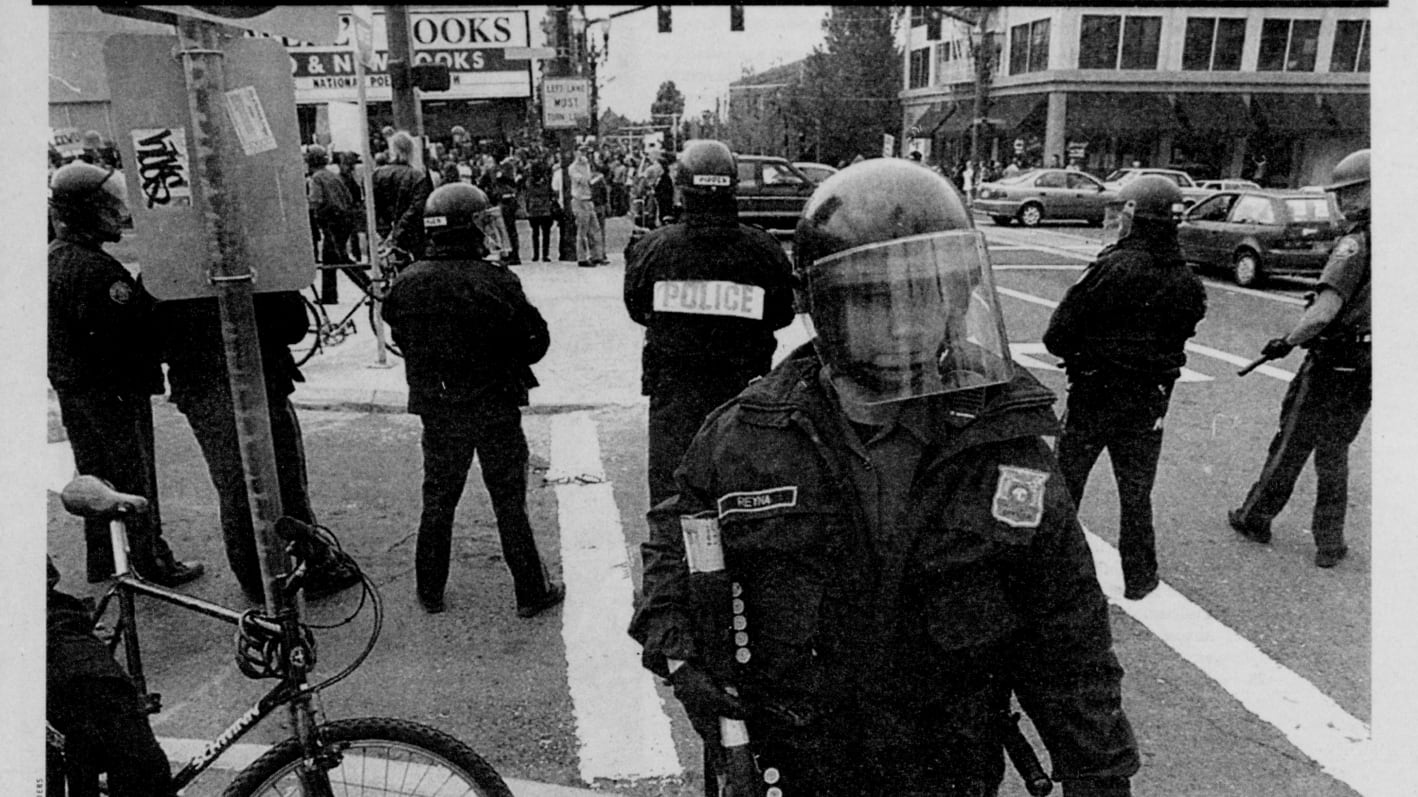

The police responded with overwhelming force: 150 officers, most in riot gear, were waiting for a crowd of 350. By the end of the day 19 protesters had been tossed in jail and at least 20 injured (see “The Walking Wounded,” below).

It was a sharp departure from previous Portland protest marches, where demonstrators and police have largely coexisted. Many who witnessed the events, either in person or on TV, came out of the experience wondering whether it was actually the men and women in blue, not a few kids in black, who were more to blame.

In reaction to the furor, the Police Bureau has commenced an internal review of its handling of the event. And Mayor Vera Katz, who initially defended police tactics, called a public forum for Tuesday, May 9, to let citizens sound off.

In a couple of months, things may blow over. But it’s clear that something has changed in Portland. For many, that change is symbolized by one man: Mark Kroeker.

Katz announced in mid-December that Kroeker, a former deputy chief with the Los Angeles Police Department, would be Portland’s 43rd police chief, the first out-of-towner to take the post in more than a quarter-century. Kroeker, the mayor said, was the perfect man to “take community policing to the next level.”

The 55-year-old Kroeker was an easy choice, given his charisma and credentials. Kroeker was the man the LAPD sent into the ghetto in the wake of the Rodney King riots. Twice a finalist for the department’s top spot, he quit in 1997 to be second-in-command of the United Nations police force in Bosnia. Since then he’s been a law-enforcement consultant for clients in Europe, Asia, Africa and Israel.

With a military bearing and close-cropped hair, Kroeker displays intelligence, humor and a thoughtful manner. He is politically astute, calm under fire and acutely conscious of public perception.

In a Jan. 5 speech before X-PAC, shortly after his arrival, Kroeker drew laughter and applause from what, seconds before, had been a potentially hostile audience of liberal Gen-Xers. “I have spent 32 years in the Los Angeles Police Department,” he said, “but I want you to know I have not come here to bring the LAPD to Portland.”

The quip served to defuse tension over Kroeker’s history with a police force that boasts an international reputation for corruption and brutality.

In an interview with WW last week, Kroeker spoke about the importance of cooperation between the people he employs and the people he serves.

In that respect, Kroeker is in step with his two predecessors, Tom Potter and Charles Moose. Still, it’s clear that Kroeker will run this police force with a substantially different style. In L.A. law-enforcement circles, Kroeker was known as “extremely rigid,” says Penny Harrington, a former Portland police chief who now heads the L.A.-based National Center for Women and Policing. “It’s very militaristic; it’s very ‘Don’t question, just obey orders.’”

It’s telling that one of Kroeker’s first actions upon coming to Portland was to propose a new grooming code: No hair below the collar, no ponytails on male officers, no beards, no earrings while on duty, and no mustaches that venture beneath the upper lip.

Kroeker says his reasons, in part, are practical. The bureau’s new gas masks, he says, don’t seal properly over facial hair. Ponytails and earrings, he says, are too easy to grab should an officer get in a fight.

But the new chief also concedes that the grooming code, used in most big cities, would be very much about building unity. He called it a symbol “that we belong to some team,” one that creates “organizational pride.”

He also said cops should look the way people expect cops to look: like they are “there to do business.”

Internally, the new standards have gotten mixed reviews. While some officers like Kroeker’s proposal, others say that the current, more relaxed rules allow individuality and make it easier to avoid the alienation so common between civilians and police.

Externally, Kroeker concedes, there’s been less enthusiasm for his idea. Harrington, for one, isn’t surprised. “I was the one that did away with the grooming standards,” she recalls. “My big thing was to try to get the police to be a part of the community. How could you make them part of the community if they look like a military invading force?”

Which is an apt description of what the Portland police looked—and some say acted—like on May 1 (“Panic in Portland,” WW, May 3, 2000).

The main May Day march kicked off at 3 pm on the South Park Blocks as many Portland demonstrations do, with dancers, kids, drummers, and plenty of signs and slogans. But it was clear from the start that something was different. It wasn’t just the number of police officers present, it was what they were wearing and carrying.

As the colorful mass of marchers wound through downtown, cops shadowed them in 12-person squads arrayed in military formation, officers wearing helmets and brandishing their standard-issue PR-24 batons. In each squad one or two officers had a crowd-control shotgun slung over his or her shoulder, its stock painted bright yellow to indicate that it had been modified to fire beanbags filled with lead pellets.

Five members of the mounted patrol were on hand, as were four officers on shiny red ATVs and approximately 10 motorcycle cops. Some officers moved about with video cameras recording protesters’ appearances and actions. Detectives stood by, primed for mass arrests.

According to the chief, the decisions about the number of officers and the riot gear they carried were made by Cmdr. Larry Findling and Assistant Chief Bruce Prunk and approved by Kroeker in the days leading up to the march. Kroeker says the decision was based on the size and intensity level of the crowd expected and its lack of a parade permit.

An unscientific survey of police officers and longtime activists indicated that the police presence that day was substantially different from other protests.

The outfits and number of officers were not the only differences.

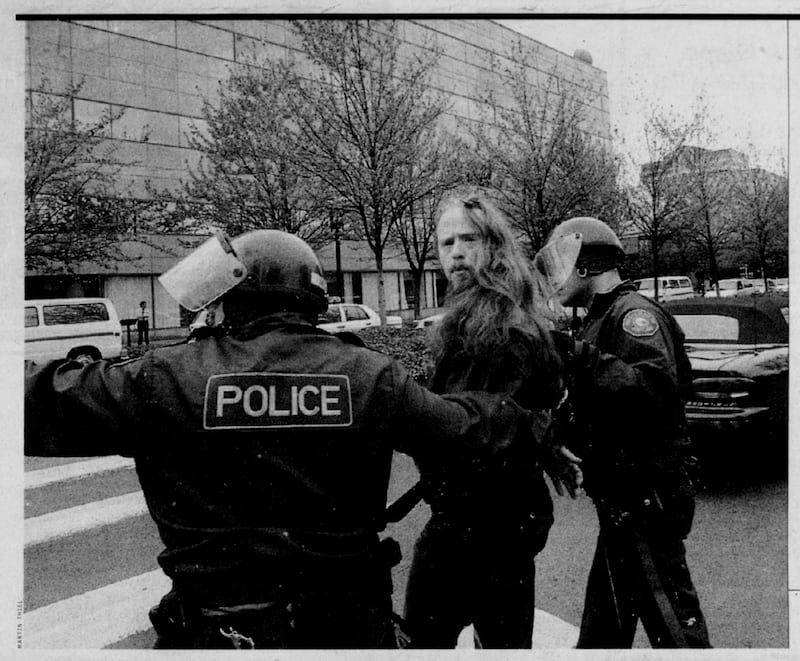

In several incidents witnessed by WW reporters or captured on videotape, police took actions against demonstrators that appeared to err on the side of unnecessary aggression.

There were clearly protesters who were out of line. A videotape viewed by WW clearly shows that at one point someone tossed a red plastic newspaper box toward a mounted cop. A reporter witnessed a young marcher vainly trying to flip a police ATV. Police also say someone in the crowd threw lighted firecrackers at officers, that someone painted graffiti at City Hall, and that someone threw a brick through a window at Niketown. Protesters attempted to block the intersection of Southwest 5th Avenue and Main Street, said Prunk. “They initiated the contact,” Prunk said. “The police did not go out of their way to initiate any contact. I think we were very measured and restrained in our response.”

But not everyone agrees. It’s clear that police in several instances reacted with a degree of haste and force that Portlanders had not seen before.

“I saw things that provoked a lot of questions for me about how community policing works at street level, and whether the tactics used were suppressing bad behavior, or instigating it,” says City Commissioner Charlie Hales, who observed the march.

At Southwest 5th Avenue and Main Street, mounted police charged the marchers, pressed them against a downtown bus shelter. At Waterfront Park, an officer clubbed a young man in the knee. Limping away, he was knocked to the ground by a cop on horseback—apparently for moving too slow. Another officer panned the crowd with his beanbag shotgun before shooting two marchers in the back and legs at close range. Their only visible offense was not moving fast enough.

Perhaps the day’s most disturbing event, which occurred on the edge of Waterfront Park, was captured on videotape and shown on the TV news. The tape shows an unidentified riot cop aiming his shotgun at protesters who are walking away calmly. He fires several rounds at them for no apparent reason, causing them to flee. After the shootings, the video shows police circling a man who’d fallen to the ground and leading him away in handcuffs.

According to Police Bureau policy, beanbags shot at targets who are within 30 yards should be aimed below the waist. Yet the video clearly shows that the barrel of the gun was horizontal, meaning the officer was firing at the backs of the fleeing marchers, not their legs—an apparent violation of department policy.

Although the guns shoot tiny beanbags of lead pellets, rather than bullets, they still can do serious damage. As the department’s 1997 general order on use of the weapons says, “Less lethal munitions are not intended to produce deadly effects, but just as with other impact weapons, they can cause serious injury or death.”

Detective Sgt. Mike Hefley, a police spokesman, says that, in general, the guns can be used whenever an officer would be justified in using a baton. He says officers should first try to control a person verbally, then escalate up the “continuum of force” using the threat of force and then, if needed, force itself. It’s not clear from the video whether this process was followed.

“We realize you may have to go up this continuum of force very rapidly,” says Hefley. “You may have to skip some points in between depending on what that person does.”

Judging the proper level of crowd control has always been one of the toughest things cops do. It’s even tougher given what happened in Seattle, where police were unprepared for the WTO protests.

‘Times are changing, techniques are changing,” says Hefley, defending the level of force involved on May Day. “Wait until we show up and we’re undermanned—and then it’s the police’s fault. No matter what we do, we’re going to make some people unhappy.”

Kroeker agreed that the May Day response was triggered not only by what Portland police observers, including Findling, saw in Seattle, but also the 1992 Rodney King riots in L.A., which the chief attributed to “an underreaction” by police.

“We have to keep the city safe,” said Kroeker. “We have a recent history that shows what can happen when you don’t.”

The police response last week in Portland was “very L.A.,” says former police chief Harrington. “That’s the way they do things,” she says, “a show of force and very aggressive.”

Last year, before Kroeker came on board, a crowd-control specialist from the Los Angeles County sheriff’s department gave Portland troops 16 hours of “mobile field force training.” Officers learned to move in formation, march in cadence and stand in a uniformly prescribed stance.

Some police say the militaristic manner is designed to inspire fear and, in theory, is more effective at crowd control and dispersal.

The new chief clearly embraces the strategy. “I am satisfied that this event was handled well,” he told WW last week. At the same time, he acknowledged that he is reviewing the incident in which the officer was caught on videotape shooting at the backs of protesters. And he will participate at the Tuesday forum, in which police and protesters will relate their versions of events.

Even some officers are questioning the bureau’s handling of the protest, though for different reasons. Police union vice president Tom Mack says individual officers without backup were sent into situations where they were swarmed by “potentially hostile” crowds.

So, what does all this mean for Portland?

One could argue that, with its loose grooming standards and relaxed attitude toward protests, the city has been in the Dark Ages. This isn’t Mayberry, after all, and perhaps it’s time Portland had a professional, big-city police force. Prior to last November, the department had not done any real crowd-control training in 15 or 20 years, says Capt. Robert Kaufman, head of training.

Criminologists are of two minds on the LAPD style of leadership that Kroeker is bringing to Portland. Some say a paramilitary departmental culture does not rule out a progressive community-policing program. Others say a paramilitary culture leads to an us-vs.-them mentality, and increases the likelihood of events such as the savage beating of Rodney King.

Kroeker concedes that his cherished ideal of a trusting relationship between cops and community is at odds with television images of helmeted Portland police firing shots into crowds of protesters. Even if the use of force is appropriate, “it’s very physical and it evokes visceral reaction,” he says. “People see something that provokes distrust, it looks bad. That’s a big task that we have, to rebuild trust.”

It’s clear that if this is the new Portland Police Bureau, it certainly failed some parts of its first big test. “What I observed was not pretty and was not, in my opinion, community policing,” says Hales. “And it was- n’t Portland, either. In L.A. maybe it’s true that every public gathering might be seen by police as a potential threat. Here it’s as likely to be a City Club committee as an incipient riot.

“Portland is a city where people take politics and public life seriously, and they exercise their right to have an opinion and express it in public,” Hales continues. “And that, to me, isn’t a clear and present danger to public order.”

The Walking Wounded

Following the May Day march, police reported that no injuries had occurred. That was news to John Paul Cupp, who was seen on videotape getting shot at close range by an officer with a beanbag gun before his arrest. According to medical records Cupp released to Willamette Week, he was treated at Legacy Emanuel Hospital on May 1 for wounds to his left calf and thigh. His calf wound had to be closed with stitches.

Cupp wasn’t the only one who came out on the losing side of May Day. WW found 20 people who say they, or someone they saw, sustained injuries of varying degrees of seriousness.

All but Cupp requested anonymity, saying they feared retaliation.

Police say one officer’s leg was bruised when a newspaper box was thrown at him.

• A female protester who says she was whacked in the hand by a police baton at the corner of Southwest 5th Avenue and Main Street. The woman received treatment at Peacehealth Urgent Care in Eugene on the morning of May 2, and was treated for a thumb broken in three places. The woman, who asked not to be named, had four pins implanted in her thumb May 5, according to medical records reviewed by WW. She is now on painkillers and says she will miss six weeks of work.

• One person with a head laceration and another person with bruised arms; both injuries allegedly sustained during arrests of marchers in Northeast Portland before the downtown protest. Reported to WW by Alan Rausch, a neurosurgical registered nurse at Legacy Emanuel who says he saw both people while they were in custody.

• Four marchers with injuries ranging from open cuts and swelling bruises to a sprained thumb. Reported to WW by a registered nurse practitioner who requested anonymity.

• A female protester, who requested anonymity, suffered black eyes, a bump on the head and bruised knees, which she says came after a police officer physically ran her over on foot. Documented by medical record reviewed by WW.

• A woman who can be seen on videotape being rammed by a police horse suffered bruised legs; the bruises were visible three days after the march.

• A man who says he was roughed up by police had a laceration on his arm, which he showed to a reporter the evening of May 1.

• A man WW witnessed being batoned by a police officer and, later, knocked to the ground by a police horse says he suffered a bruised knee. His medical record was not available at press time.

In addition, WW talked to eight other people who say they sustained injuries in the march, ranging from a bruised liver and a head laceration to bruises and scrapes.

Marching to Different Orders

Police arrested more people last Monday than they did during the three weeks following the start of the Gulf War in 1991, when thousands marched weekly in a city that became known as “Little Beirut.”

But to get an idea of just how much the Portland Police Bureau has changed its response to protests, you only need to go back six months.

On Oct. 15, all the ingredients were ready for a showdown between protesters and police. More than 300 people (about the size of the May Day march) gathered downtown to support Mumia Abu-Jamal, a Pennsylvania death-row inmate accused of killing a Philadelphia cop. Abu-Jamal, a former journalist, has become a cause célèbre for activists and a hated figure for cops.

The prospect of activists marching about downtown urging freedom for a convicted cop killer must have galled some of the approximately 50 Portland cops on hand.

But they let the march proceed unmolested; even the police told WW that the march was incident-free. Although one riot squad appeared, it kept its distance, and no beanbag shots were fired. The scene was tense but in control, at least until the last protesters were clearing downtown’s Terry Schrunk Plaza. That’s when police moved in and arrested Chad Hapshe for dropping a flower on the sidewalk. Then, when confronted by veteran activist Craig Rosebraugh, an officer broke Rosebraugh’s left arm while tackling him to make an arrest (“Strong-Arm Tactics,” WW, Oct. 27, 1999).

The local activist community was outraged.

On Oct. 22, they held a march to protest police brutality. The event drew perhaps 125 people, who marched from Northeast Portland to the downtown Justice Center. Although the marchers had no permit, police allowed them to proceed without interruption. The strategy worked. As the march wound down, the exchanges between activists and police were, in many cases, downright friendly.

That was then. This is now.

Following May Day’s meltdown, about 125 activists gathered in the North Park Blocks last Thursday afternoon to protest police conduct, just as protesters had six months earlier. They hefted signs reading “Keep L.A. tactics out of Portland” and “Kroeker brand pork and beanbags” with a slash through it, the international NO symbol.

Speaker after speaker denounced the police through a megaphone. Five mounted police sat atop their horses, looking as if they’d swallowed castor oil. After activists moved onto Southwest 2nd Avenue, 24 riot cops and 20 more officers eyed them from across the street, while a platoon of television cameramen stood waiting.

As the marchers moved south toward Stark Street, a third squad of 12 riot police trotted into view. The marchers edged toward the crosswalk.

This time, there would be no good-natured banter to defuse the situation. One of the riot cops stepped forward and, holding the barrel of a beanbag gun to the sky, pumped the action. He didn’t pull the trigger. He didn’t even level the gun. The protesters turned west, bound for Pioneer Courthouse Square.