Among her many talents—novelist, columnist, bartender—Katherine Dunn was a terrific boxing writer. In the 1980s, she regularly covered fights for WW. But the bouts she covered in January of 1985 were different: She traveled to Lake Tahoe with one of Oregon’s most promising young fighters, Andy Minsker, to see if he could make the jump to stardom.

This story first appeared in the Jan. 21, 1985 edition of WW.

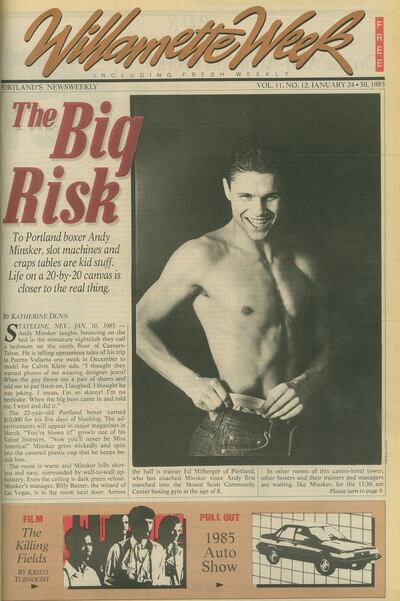

STATELINE, NEV., JAN. 10, 1985 — Andy Minsker laughs, bouncing on the bed in the miniature nightclub they call a bedroom on the ninth floor of Caesars-Tahoe. He is telling uproarious tales of his trip to Puerto Vallarta one week in December to model for Calvin Klein ads. “I thought they wanted photos of me wearing designer jeans! When the guy threw me a pair of shorts and told me to put them on. I laughed. I thought he was joking. I mean. I’m so skinny! I’m no beefcake. When the big boss came in and told me, I went and did it.”

The 22-year-old Portland boxer earned $10,000 for his five days of blushing. The advertisements will appear in major magazines in March. “You’ve blown it!” growls one of his Tahoe listeners. “Now you’ll never be Miss America!” Minsker grins wickedly and spits into the covered plastic cup that he keeps beside him.

The room is warm and Minsker lolls shirtless and easy, surrounded by wall-to-wall upholstery. Even the ceiling is dark green velour. Minsker’s manager, Billy Baxter, the wizard of Las Vegas, is in the room next door. Across the hall is trainer Ed Millberger of Portland, who has coached Minsker since Andy first marched into the Mount Scott Community Center boxing gym at the age of 8.

In other rooms of this casino-hotel tower, other boxers and their trainers and managers are waiting, like Minsker, for the 11:30 am weighing in ceremony so critical for that evening’s fight card.

Beyond the windows, Lake Tahoe lies gunmetal cold and restless. It is caught in the raw stone teeth of mountains flimsily disguised bv snow. Million-dollar homes are supposed to be tucked away in the forests around the lake. The road from Reno snakes upward in ear-popping curves through dense fog and snow. The few A-frames visible by their lights look as fragile as pup tents among the surrounding trees. The road gives a final twist, then spills out of the wild night into a shock of spangled high-rise neon, like a spark blown clear from Las Vegas to flame up among the dark, wintering firs.

There must be service stations here, maybe even a grocery store. Somewhere close is a small airport, often closed by winter weather. All signs of normal life are shunted out of sight. The sheer mountain walls lean close, their bases invisible behind the shoulder-to-shoulder casino hotels. Each of these establishments is a small, crammed city, so complete that you could spend weeks and fortunes without ever stepping outside its doors or catching a glimpse of the snow veils dancing off the peaks above you. The Vegas casino clones of Caesars, Harrahs, Del Webb’s High Sierra, and The Nugget all elbow up to the mountain road, offering a 24-hour, year-round wingding with risk as the main attraction.

This little Vegas is complicated by troops of skiers clumping through in pastel nylon, but the clinking glitter is Vegas all the way. Risk is the item for sale here, and it is in big demand. Thousands save up to buy a Saturday of blade walking or scrimp all year for a two-week binge. The knife-bright days on the ski slopes see crowds of people throwing themselves into long, hissing descents that trigger the adrenal roar in their innards. Nights in the casinos, they buy their risks a coin at a time.

There is no piped music in these vast, tangled rooms with their battalions of slot machines and phalanxes of blackjack, craps and roulette. The music here is the tantalizing chunk of the one-armed bandits and the electric beep of a victory tune with a rattle of coins for the bass line. There is food for the body at in-house restaurants. Patrolling waitresses deliver liquid-nerve refills anywhere on the floor. For a breather from putting your neck on the line, there are the big shows with big-name entertainers — and tonight, at Caesars, there is boxing.

The sport of boxing is evolving into a symbiotic orchid rooted in gambling casinos and energized by the grow-light of national television. The old fight centers of New York and Los Angeles are relegated to farm team functions, staging club shows in the once great fight arenas of Madison Square Garden and the Olympic. But the big bouts, the champions and top contenders, display their strange, contentious game for television audiences from the ballrooms, supper clubs and parking lots of the big casinos in Atlantic City and Nevada.

The casinos pay enormous site fees to the broadcast and cable networks for the privilege of staging a boxing match. The TV exposure is a stupendous enticement to potential visitors, and boxing itself sucks live crowds into the casinos’ tempting corridors. Boxing is almost as popular a sport for bettors as football and basketball, and, with TV backing, it can be profitable even in a small arena. The TV industry loves boxing for its full minute of commercial advertising time after every three-minute round. The viewer ratings are high all through the year because boxing provides a risk event of ritual crisis that appeals to that part of us that jaywalks and fantasizes about putting the house, the car and the wedding ring down on a longshot.

Caesars Palace in Las Vegas is the site of many of boxing’s most spectacularly profitable matches. Now, with ESPN cable TV promoting a nationwide tournament on Top Rank’s weekly boxing shows. Caesars Tahoe is getting in on the action. Tonight’s show will be the first in a monthly series planned for this site.

The card tonight includes two middleweight boxers in the elimination rounds of the ESPN tournament. The posters read like a Portland fight night with no fewer than three Portlanders on the card.

Delbert “Mean” Williams, the Northwest middleweight champion, a cheerful character despite his ring name, is here for his crack at the tournament. Matched with slick-boxing Charles Campbell of Fort Worth, Texas, who is favored to win the tournament, Williams is in tough. His manager, Portland’s Fred McNally, and his trainer, Arnold Manning, arc quiet and edgy.

Doug “The Sleeper” Holiman, a Portland veteran of 12 wins and seven losses as a middleweight, is in for 10 rounds with a brawling hero named Nicky Walker from just down the road in Carson City. Holiman’s friend and manager. Wally Jorgenson. has a confident manner and a furrowed brow.

Noe Ramirez, a former high school wrestling champion from Sunnyside, Wash., has fans in Portland but will be alone in the ring with a California monster named Luis Santana. His manager, Bruce Seibol, editor of the Northwest Boxing Review, thinks Noe will win.

The elevation of Lake Tahoe is 6,200 feet — quite a jump for flatland athletes. They shrug it off, saying, “It will affect the opponents the same way.”

Among the fight-game insiders, less attention is focused on the veteran performers than on the scrawny wisp of a pre-lim kid coming in for his second professional bout. Portland’s Andy Minsker. the national amateur 126-pound champion in 1985 and an ‘84 Olympic alternate, is under intense scrutiny. The glut of new talent entering the professional game following the Olympics is led by the richly medalled U.S. team members. Minsker. who easily outpointed gold medallist Meldrick Taylor in the U.S. trials only to lose to him weeks later in the boxoff, is seen as a force to be reckoned in the same class as the Olympians.

Billy Baxter, manager of two world champions, picked up Minsker’s contract. A promotional agreement with Top Rank and ESPN guarantees that all of Minsker’s fights for two years will be televised. Ed Milberger, Minsker’s trainer, says, “These knowledgeable types seem to think Andy could do something.”

Minsker, the cougar-faced string bean from Milwaukie, has boxed since he was eight years old. Now, as the popular but demanding coach of the junior boxing team at Mount Scott Community Center. Minsker is dedicated to the science of the sport. He can, as the gym rats say, box a bit. In the highly competitive 126-pound division, Minsker looks like a fair bet for future rankings. At 5′10″ he has a four- to six-inch reach advantage over 98 percent of the division. He has fine technical skills, a scrappy style and a snappy punch.

What interests the TV money guys, however, is Minsker’s complexion. Boxing is so demanding that it has always been the turf of the poorest and of the most recent immigrant minorities. Though fight announcers distinguish opponents discreetly by the color of their trunks, the multimillion-dollar popularity of Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini and Gerry Cooney is a constant reminder of the novelty and sheer cash value of a decent white fighter in a game now dominated by blacks and Hispanics. When such a one crops up, the cash registers tingle with excitement.

This rarity factor is a marketing advantage, but it is also grounds for extended suspicion. Can he really fight? And. if he can, will he stick with it?

The day before a fight, you rest. You don’t eat much. You don’t drink at all. When fight-day morning rolls around, your mouth is flannel and you are anxious to he weighed. “Liquid puts the weight on,” says Andy, spitting into a covered plastic cup. Spitting is a strength-conserving way to get rid of fluid and weight.

The time passes slowly. “Home in Portland.” says Minsker, “I’m always busy with [commercial upholstering] school and training and work on the car. There are fish to be caught and little kids to be taught.” The thrifty Minsker is known to use the waiting time to embroider slick, satin-stitchcd names on other boxer’s gear “for fifty cents a letter.”

As the 11:30 weigh-in time approaches. Minsker moves fast in his dress sweats, sailing past the rows of hypnotic gambling devices toward the indoor swimming pool. Though he fought many times in casinos as an amateur, Minsker doesn’t seem to feel the lure of Lady Luck. “The worst thing about these places,” he says, “is that there’s nothing to do. You go nuts.”

Caesars’ management would be appalled, but Minsker is strictly a high-stakes gambler. The speed of a pony or the random temper of a machine interest him no more than an upward trend in pork-belly futures. His is not a something-for-nothing fantasy. He risks years of constant grueling effort, physical pain and danger, as well as the scorching public exposure of every error. He bets everything he is and has on himself.

The weigh-in happens next to the elaborately curving green-lit pool. Boulders are stacked in and around the pool, forming caves and grottoes that arc softened by potted plants and furnished with upholstered deck chairs. Three young women practice an aquatic-dance routine at one end of the pool, ignoring and being ignored by the 50 or more men hustling around the official scale at the other end. The usual hodge-podge of managers, trainers, matchmakers. and reporters is swollen by ESPN TV crews and Top Rank officials. The team of announcers who will explain the fights that night sit hunched over clipboards, scribbling notes as they talk with one boxer after another.

The old-time reporters drink and smoke too much. The old-time fight guys have chronic indigestion due to the unpredictability of their chosen work. The pallid and the paunchy stand around eyeing the racing-trim boxers. A legendary gym rat peers out through a clump of trailing ferns, as two by two the fighters strip to their underwear for the crucial trip to the scales. He untangles the sodden cigar stump from his rumpled mug long enough to mutter, “Used to be ya could tell something by whether a guy wore jockeys or boxers. Whatever happened to Fruit of the Loom?” He shrugs and plugs the cigar back in.

It’s suddenly a fashion show. Delbert “Mean” Williams, fresh from a calm morning ensconced on a bar stool in front of a one-armed bandit, is in a red-and-blue-striped bikini, lie steps off the scale to be replaced by his opponent, Charles Campbell, in silver-gray nylon with hip notches. The 10 sculpted fighters strip off their dress sweats in turn, and no two of them have the same kind or color of underwear. Minsker’s looks fairly conventional unless you notice the Calvin Klein stencil on the waistband. His opponent, the sturdy, silently determined Lamont Baker, is in royal-blue knit.

The sharp eyes of this crowd are not impressed with fashions. They focus on the corrugated bellies. The wisecracks are to kill time while they size up the opponent’s skin texture, muscle tone, arm length, and an indefinable something in the eyes and around the jaw. The search is for clues not just to physical condition, but to the states of mind that will determine the night’s results. The boxers eye each other quickly. They are in a hurry to be done with the ritual. Most of them are hungry and all of them are thirsty.

Having made his 126-pound contract weight, Minsker it in the restaurant smothering two flapjacks with strawberries. Talk among the fight folk and reporters at the long table turns to a recent call by the American Medical Association to outlaw boxing. Though fighters and managers have heard the howls many times before, it always bothers them. Why is boxing the scapegoat? they wonder, and answer among themselves: “The doctors have their problems. All these malpractice lawsuits. People aren’t treating them like gods anymore.” The fight reporters talk hopefully about a national commission. Several black and Hispanic fighters listening shake their heads ruefully. “Yeah, that would be good,” they agree, knowing all too well that there is no billion-dollar lobby to promote their interests in the corridors of power.

Minsker, for all his years in the sport, is wounded by the AMA’s criticism. His shoulders hunch defensively. “I don’t understand why they’re attacking boxing. Why don’t they talk about jockeys or hockey or football? A lot more guys die. Those guys get brain damage too. No boxer gets his spine snapped and gets paralyzed or gets all those fractures and internal injuries and their joints ruined!” His hands grip and run across his arms as though feeling them for breaks. “Well,” he decides, brightening, “Maybe it ain’t the best thing in the world to do. But it’s got me every place I’ve ever gone, everything I’ve had. I’ve gone to New Zealand and Scandinavia and all over the United States, and I’m making money now that nobody makes without going to a four-year college.”

Changing the subject to shake off the depressing thoughts about the AMA’s condemnation, he explains his new haircut. The hair has been clipped to the scalp on the sides and around the back with a short greased thatch left on top. “My sister’s been cutting hair for years. I took her this picture of Jack Dempsey in the ring with this giant — must have been Jim Jeffries — and she did mine just like Dempsey’s.”

Minsker weighs 70-odd pounds less than Dempsey did in his prime. Perhaps Minsker more resembles another featherweight, the great Sandy Saddler, who was called the Praying Mantis because of his stick-thin body and great height. But Saddler was only 5′8″. Minsker. with another two inches, resembles that predatory insect even more. He laughs, teasing manager Billy Baxter for worrying that he might not make weight: “Last night at dinner, every time you’d take a bite you’d look over to see what I was eating!” Minsker thinks this is hilarious since he has never had a weight problem. Baxter nods amiably now that the scales are satisfied but reminds Minsker that his opponent, Lamont Baker of Las Vegas, is a good fighter who has been training hard. “I predict,” says Baxter, “that this is going to be a tough fight.”

Baxter, 44. a genial, blond bear with a sharp nose and sharper gray eyes, is a professional gambler whose success at world-class, high-stakes poker has earned him the moniker “Bluffing Billy.” His gently precise Georgia diction warms the nation’s sports handicapping phonelines, and his shrewdness in assessing the prospects of teams and individuals, from football to boxing, has earned him millions. The crusty boxing establishment, which scorns anyone who hasn’t been in the game since the Flood, has accepted Baxter as a fight manager, partly because of his unpretentious charm, but mostly because even the magi can’t argue with success.

With a new, untried fighter in Minsker, Baxter is still exploring and testing. Lamont Baker trains in Las Vegas, and the manager knows that Baker is in good shape. Minsker trains in Portland with Ed Milberger, and reassuring phone calls are never as convincing as your own eyes. Baxter knows how hard the change from amateur to pro can be. He also knows that this hard game can end in an instant. One punch can wipe out the TV, the modeling, the big money, and the title at the end of the rainbow.

The doors to the tiered amphitheater of Caesars-Tahoe open at 4:50 pm on Thursday, Jan. 10, and a few thousand skiers, gamblers, natives, and fight fans form a line, four and five deep, to find seats for the 5:30 show. The ring, lit white, stands in front of curtains that opened on Jefferson Airplane only last evening.

Behind those curtains, in ominous black cloth cubicles, the fighters scheduled for the early bouts wail with their corner men. Off stage, down a corridor, past the big restaurant kitchens, a double fire door swings in on a huge banquet room that appears at first as empty as a condemned roller rink. The walls are gold satin. The room is musky, unlit except for one end near those double doors. Beneath the single light, Andy Minsker and Ed Milberger sit facing each other, with their knees nearly touching, on a pair of folding metal chairs. Baxter stands close, watching as the gauze strips are wound over Minsker’s hands. “We could go in any time if there’s an early knockout. Otherwise we’re the fourth bout,” explains Baxter.

Of all the waiting in boxing, this time in the dressing room is the most delicate and terrible. The monster is outside the door and the knock may come al any lime. Boxing is, in its own strange way, a team sport. The three men with their different attitudes, ages and duties sweat together during this waiting.

Lamont Baker and his team are, no doubt, sweating close by. Minster and Baker have fought once before, in 1984, at the amateur regional tournament in Las Vegas. Minsker took that decision by staying outside and using his reach advantage, but the sturdy, determined Baker pressed him hard. Now Baker has a crack at revenge. Each fighter has just one professional victory on his record. The hundreds of amateur bouts no longer count.

The crowd roar drifts back past the kitchens to the empty banquet room. The title bout on tonight’s card is a tough middleweight tangle. Then Portland’s Delbert Williams wrangles with Charles Campbell, a lanky Texan. Campbell shows the polish of his sparring with World Welterweight Champion Donald Curry and the unmistakable stamp of trainer Joe Barriente’s teaching. Williams, exhausted after an aggressive start in this rarefied atmosphere, clinches and wrestles as the crowd begins to boo. After eight rounds, he loses the decision to Campbell.

At ringside, the commission doctor talks about the 6,200-fool altitude. “Fifty percent less oxygen in your blood than at sea level, that’s what it means,” he says. The waiting fighters and managers begin to brood. Most of them have been claiming that the elevation won’t bother them.

Noe Ramirez (11-6, 7 KOs) of Sunnyside, Wash., steps in with Luis Santana (23-2-1, 18 KOs) of Hawthorne, Calif. When Noe hits the deck in the second round, the knock on the door comes for Minsker.

The ESPN fight announcers have their information garbled. Al Bernstein says that Minsker has been training in Las Vegas and knows Baker but has never sparred with him. “We asked Andy if working in the same gym and being friends made it harder and he said, well, maybe it did.” Bernstein must have Minsker and Baker mixed up with two other guys. They are not friends.

Some fighters are stone-faced in the ring. Lamont Baker is one of them. From the first bell to the last, his expression never flickers from its stern concentration. This is considered an asset in fight circles because a boxer’s face doesn’t register when he’s stung and doesn’t reveal when he is planning a new trick.

The 20-year-old Baker is 5′6″ and built like a brick. His best bet with Minsker is to wade in close and wail on Minsker’s ribs and belly with an occasional crack at looping a right hand over Minsker’s habitually low left. Baker follows this strategy with great determination.

Minsker is never stone-faced. He peers out from under his deep eye sockets, which causes his eyebrows to climb madly for shelter in his hair. They never quite make it, but they rumple his forehead in the process. This gives him an awestruck, horrified, delighted, or inquiring look that may be as misleading as no expression since it seems to be totally unconnected to what is happening at the moment.

With his enormous reach advantage, Minsker could keep Baker at the end of his jab all night, slicing and popping the shorter man without ever getting hit. Minsker, to the knuckle-gnawing agony of his corner men, chooses not to pursue this course. He crouches until he is no taller than Baker and leans in, hooking to Baker’s hard belly on the inside. He plants his feet and claws like a wolverine.

Light-heavyweight contender Eddie Davis, when asked to define the difference between his style and his brother’s, said, “Johnny, he always loved to box. Me, I like to fight.” Andy Minsker can box, and frequently does. On this occasion he chooses to fight. Maybe he wants to wipe out any poor impression created by over-anxiousness in his Nov. 28 debut. He is obviously eager to look exciting and effective against Baker.

Reaching in, halfway through the first round, Minsker gets caught off-balance by a roundhouse right to the head followed by a shove. The floor reaches up to smack the seat of his pants, and the Portland fans who have flown, driven or hitchhiked to Lake Tahoe for the occasion nearly swallow their tongues in shock. All the way back in Portland, a thousand hearts freeze for a split second in front of television screens. He’s gone loo far this lime, and risked loo much. Minsker has abandoned his own style and his own turf, figuring he can beat Baker on Baker’s terms, play Baker’s game and win.

With more than a minute left in the round, there is time for Baker to finish him off if Minsker is dazed at all. But Minsker hops up, as if he’s just sat on a bee. It all happens so quickly that referee Norm Budder seems to assume that the boxer only slipped. Minsker goes on without an eight-count and without being docked a point for the knockdown. From that time on. Baker is always dangerous but Minsker is in control. It’s a good scrap and the crowd loves it. The announcer, Al Bernstein, finds himself being won over. “Minsker is very unorthodox but he’s fun to watch! . . . Maybe his unorthodox style will be criticized throughout his career, but it seems to work.”

Ringsiders can sec Minsker’s mouth moving. saying “Sunufabitch” as each round ends and he finds that he has still not stopped Baker. At the final bell. Lamont Baker, a good fighter in top condition, is still standing and still dangerous. (Neither guy has show any sign of being affected by the altitude.) Minsker takes the unanimous decision, winning every round on the judges’ cards. The crowd absolutely loves it. They roar all the way.

Ed Milberger is quietly furious. Doug Holiman climbs in to struggle for air in 10 rounds with Nicky Walker, and loses the decision while Ed is still muttering. Andy “sunufabitches” repentantly, and Baxter offers firm advice. Milberger says, “I’m gonna have to get fierce with him if he’s gonna go out there and do exactly what I been telling him not to do. He can be a superstar, but not if I let him get himself hurt first! Acting like a rank Amatoor!”

Baxter is happier. “He’s improved a lot. I’m pleased. Frankly nobody is going to pay to see somebody ride around the ring on a bicycle. I applaud his impulse to get in there and fight. It will make him easy to sell. But I’ve never yet seen a great fighter who leads with his head.”

The river rush of the fight crowd spews out through the big theater doors and spreads, slowing and settling among the magnetic islands of the slot machines, crap games and blackjack tables. Everyone is hot to play. Boxing does that for its audience. Every fight scholar in the back row knows what the boxers should have done, and that adrenal knowledge makes the viewer audacious for hours, like a dance tune hummed all the way home. What is a game for the gamblers is business for Caesars, and the house wins big tonight.

Doug Holiman. unscathed in his loss to Nicky Walker, is soon perched on a leather stool with a styrofoam cup of quarters beside him as ammunition against his new opponent, the one-armed bandit.

Noe Ramirez plays blackjack all night long with a grin etched into his swollen cheek. He wins a hundred bucks and is still grinning the next morning over his orange juice.

Minsker’s team, though grousing dutifully about perfection, has reason to be happy. Minsker, Baxter and Milberger gallop off to see the fight’s rerun on TV.

In a matter of days the skiers and gamblers will be back at their regular work, planning their next holiday-for-risk. The fighters will be back in gyms from Oregon to Texas, sweating and thinking, studying for their next bouts.

The message of the lights and the casino plush is “You can’t win if you don’t play the game.” The sweat-reek of the gyms whispers another song: that dreams are their own profit and risk is its own reward.

Editor’s note: Nearly 20 years later, in 1984, Chris Lydgate caught up with Minsker in retirement.