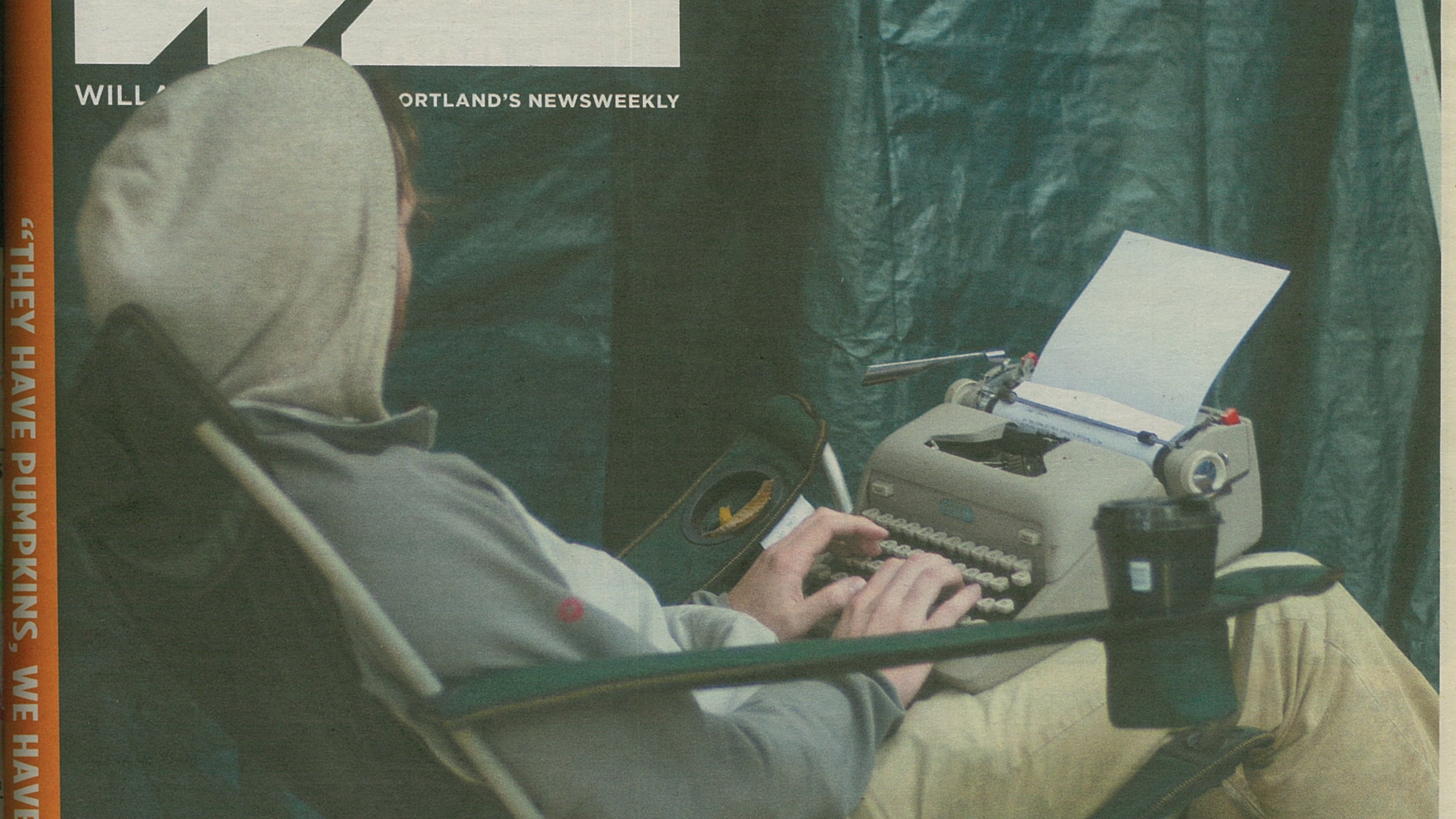

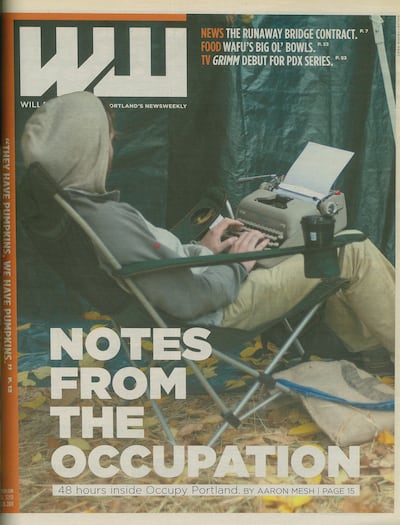

Later this year, WW will publish a book featuring 50 noteworthy covers published over the paper’s first 50 years. This is one of them. Aaron Mesh, then WW’s film critic, captures the scene and colorful cast of Occupy Portland, a more than monthlong encampment at downtown Chapman and Lownsdale squares that grew out of an Oct. 6 march of 10,000 demonstrators to Pioneer Courthouse Square to protest economic inequality.

This story first ran in the Oct. 26, 2011 edition of WW.

DJ Nick is back. He needs to get out of here, because DJ Nick is trouble.

He’s just one of the problem people the Safety/Peacekeeping Committee worries about in the Occupy Portland camps.

There’s Pinkie, with his pink Cherry 7UP jacket and pink Mardi Gras hat, who gets frantic dancing to his radio and has to be calmed down. And there’s Justin, who smears lavender oil across his expansive bare chest and yells at strangers and by morning will have a black left eye and a fresh red scab on his nose.

But DJ Nick is real trouble. They banned him last night, but he keeps returning to pick fights. He tells anyone who will listen that he’s been attacked. He falls to the ground and begs for help, his eyes puffy from crying. “I have HIV,” DJ Nick says. “I will spit blood on you.”

Mike, who supervises the night shift of the Safety/Peacekeeping detail, stands on the designated smoking corner at the edge of Alpha Camp. A two-way radio dangles from the collar of his green T-shirt. He’s tired of DJ Nick.

Just after midnight Friday, Mike decides to go to the cops. Two Portland police officers stand on the corner, known outside Occupy Portland as Southwest 4th Avenue and Main Street. He tells one cop he wants DJ Nick arrested if he returns.

The cop says they’ve already tried to deal with DJ Nick. They sent him up to Oregon Health and Science University hospital. He refused treatment. “We can cite him,” the patrolman says. “We couldn’t hold him.”

“What you need to do,” Mike tells him, “is drive him past OHSU and drop him off. It’ll take him a couple of days to get back.”

I can’t find a place to pitch my tent. Every inch of what used to be the north lawn of Chapman Square is covered with tents and tarps and pallets. The same goes for Lownsdale Square to the north. I’m moving into the Occupy Portland camps for two days so I can find out what happens when a protest turns semi-permanent in America’s most dissent-happy city.

Two weeks earlier, more than 10,000 Occupy Portland marchers wound through the city—a spinoff of the Occupy Wall Street movement that began Oct. 6. Some ended up at Chapman and Lownsdale squares, now renamed Alpha and Beta camps. Occupiers say about 500 people live here now. They say they aren’t leaving.

The Occupiers have established a democratic government, based not on majority rule but on volunteerism and consensus. They have honed their activism, holding a march a day and making their message more specific—like going into Wells Fargo last week to protest what they see as predatory banking practices.

The camp’s leaders—mostly students and recent college grads who work as much as 20 hours a day—have built social services for everyone who lives here. They provide three meals a day, clothing, trash collection, medical care, religious services and acupuncture. And they offer seminars on personal economics, mental health and crocheting.

But two weeks in the parks has also created growing stress on Occupy Portland. The bevy of services has made the camps a magnet for the homeless, who now outnumber the original protesters. The Occupy leaders find themselves dealing with some of the same social ills they have been protesting against.

For help in finding a place to camp, I go to Engineering—one of many departments set up here. It’s in a shelter made of white plastic tarps and PVC pipes. Outside, there’s a table with cups of chicken soup and part of a chocolate cake.

Anthony Dryer, with long brown hair and a yellow rain jacket, is standing nearby. He’s a cook at Sushi Ichiban who returns to camp each evening after work. And he knows where there’s empty tent space. He finds me a straw-covered mud patch 4 feet by 6, right next to Main Street with a view of the elk fountain.

My neighbor is Mario, who sits on a flattened Sierra Designs tent and plays with a beach ball marked “[Heart] > $.” Mario has no idea how to put his tent up, so Anthony and I help him. In broken, rapid English he thanks us, thanks God, tells us he’s Cuban and then sings and dances. God has given him a new heart, he says. Castro tried to conscript him into the army.

“King Obama killed the king of the terrorists,” he says. “I’m a little crazy, but I don’t drink.”

I drop off my things—a sleeping bag, a duffel with toothpaste, deodorant and clothes—and cross Main Street into Beta Camp. Dozens of Occupiers stand at the corner; everyone waits for the lights to change.

The Library is in a blue tent filled with wooden and plastic shelves. The volunteer librarian, Mark Nerys, a freelance illustrator, sorts donated books according to the Dewey Decimal System. The books include Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, Mario Puzo’s The Last Don and Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight.

“We make them all available,” Nerys says. “No censorship here.”

Nerys has helped run the Occupy Portland Library since the beginning, except the two days he went home with strep throat. It has more than 200 books, and Multnomah County librarians are helping catalog them. The pride of the Library was a collection of law books, including an especially prized volume on white-collar crime, until someone stole the entire set last week.

From the outside, the Occupy Portland encampment is a confusion of tarps strung with crisscrossing yellow cords tied to Chapman and Lownsdale’s giant elms. Passersby also see signs—a nearly unbroken wall of signs—condemning Wall Street, “Banksters” and the 1 percent, the tiny sliver of Americans who control 40 percent of the nation’s wealth.

“We are the 99%,” says one. “Veterans are the 99%,” says another. “Hip hop is the 99%.” On the back of a Hollywood Video closeout-sale placard someone has written, “Smile! The entire world is watching.” (The “o” in world is a peace sign.) Another has a drawing of an extended middle finger: “Put a bird on it.”

Inside, the camps have a thicket of tents and a remarkable array of services. In Beta Camp, families with children have pitched their tents around Kids’ Camp, a tarped enclave that smells like talcum powder and is filled with boxes of crayons, stacks of DUPLO blocks, piles of dolls and a flag featuring Che Guevara.

“Honestly, I’ve never had a moment when I’ve doubted bringing my son here,” says Kate Sherman, who’s dressing her 16-month-old son, Tupac, in a fuzzy green onesie.

Alpha Camp has a 24-hour cafe with a plastic canteen of coffee. “Sorry! We are out of mugs,” says a sign. KBOO community radio broadcasts from a makeshift studio under a blue tarp, complete with an ON THE AIR light. They’re giving away sweaters and socks in the next booth. Other tents are named Relax, Octopi Portland, Beer Mecha. Across the sidewalk is Information, with tables covered with handbills. Next door is Safety/Peacekeeping.

Nearby, there’s a noteboard marked “Missed (Romantic) Connections” where people have left yellow Post-its: “I love when you tickle me until I can’t breathe.” “I was the sexy guy with the ‘Free Therapy’ sign.” “Damon I am here! Love Mom.”

Another board urges responsibility. “No Means No,” says a poster. “I’m Not Sure Means No,” “You’re Not My Type Means No,” and “Let’s Just Go to Sleep Means No.”

It’s 10 paces from the part of Alpha Camp that feels like a utopian commune to the south side, known as “A” Camp, which has become a hangout for street kids.

Anarchists and crusty punks control “A” Camp. A kid stores a white Bic lighter in his stretched left ear-piercing hole. One man in a frayed sweater steps in front of strangers and says, “You want to see my testicles?”—and then holds a rubber scrotum in their faces.

Pit bulls are on leashes; two white huskies drink out of a Benson bubbler. A black-and-white pet rat scurries down the overalls of a woman in braids until only his tail shows. “I’m sorry,” she says, “he’s very antisocial.”

A kitten named Marley Killface perches on the shoulder of a man with a studded leather jacket. The kitten is wearing his own tiny leather jacket decorated with metal clothespins.

The Safety/Peacekeeping Committee has enlisted many of the street kids to help keep an eye out for trouble. “The homeless people are guarding the homeless people,” says Michael Withey, a clean-cut man in his 40s who volunteers on the Finance Committee. “And it’s just not working.”

While Occupy Portland is a grassroots democracy, a clear authority structure has emerged within the camp. Its operations are run by more than a dozen committees: Finance, Legal, Outreach, Chaplains, Sanitation. A new one forms whenever someone can amass support and volunteers for it.

Members of some of the more influential committees wear armbands to identify their roles. Information has black lettering, and Safety/Peacekeeping has blue.

Not everyone is getting along. Withey has organized a meeting between Occupy Portland leaders and city parks officials. Another committee leader tells him he doesn’t recognize Withey’s authority to schedule the meeting.

“Whatever,” Withey says. “If nobody wants to show up, don’t show up.”

After two weeks in camp, Withey’s grievances have reached a point where he declares aloud what other committee members will confirm during my stay.

“More than half of the Occupiers here are homeless people,” he says. “Quite honestly, a lot of them don’t know what the movement is.”

An “A” Camp resident named Tyler, with blond hair neatly combed and breath that smells of alcohol, complains that the city shut off an electric-car-charging station along Southwest 4th Avenue. Occupiers had run extension cords from it to charge cell phones.

“You know why they’re not shutting us down?” Tyler says of City Hall. “Because they like us to live like this. ‘Y’all are peasants.’ They’re doing free hugs in here, because there’s a lot of people who haven’t even had a hug for a long goddamn time.”

About an hour later, Tyler is in the group of “A” Camp residents helping Safety/Peacekeeping when DJ Nick shows up. DJ Nick threatens to spit blood on Tyler.

“You’re lucky I don’t get a hammer and cave your head in,” Tyler shouts.

It’s 6 pm, and the most impressive operation of Occupy Portland is now under way: dinner.The 20 Kitchen Committee volunteers serve at least 1,500 people every day. They’ve transformed the centerpiece of Lownsdale Park—a 1993 bronze statue of a pioneer family called The Promised Land—into a mess hall covered by massive blue and white tarps.

The statue’s marble base supports racks of ginger, oregano, Parmesan cheese, sea salt, barbecue sauce, mustard and maple syrup. A sign nearby says, “First the Dishes, then the Revolution.”

During my stay, I will eat bowls of red beans and rice, and cream of mushroom soup, a tangy tomato and cucumber salad, and a plate of flavorless, sticky glop made of potatoes. There’s also a pony keg of kombucha.

The kitchen crew has limited electricity and no refrigerator. They cook with whatever is donated each day—much of it from factory farms. Many Occupiers worry they’re not being sustainable.

“Prepackaged meat pasta in cans?” says Chris Klitch, an unemployed 27-year-old chef and Kitchen volunteer. “That’s not helpful. That’s not food, even.”

Klitch looks resignedly over at the serving line, which has run out of forks.

“You better not be putting out plasticware,” he mutters.

In Terry Shrunk Plaza, just south of Alpha Camp, it’s time for General Assembly. Occupiers call it GA and convene every evening at 7 pm. The meetings are supposed to be finished by 10 pm, when the plaza closes to the public, but they’ve lasted as long as seven hours.

GA Committee members want to limit clapping, which they deem disruptive. They’ve created seven silent hand gestures to express opinions. “Twinkles,” or fingers waved in the air, signals support. “Down twinkles,” fingers wagged at the ground, signals disagreement. They look silly at first but actually do keep the meetings flowing.

Tonight one man comes forward with a proposal urging camp residents to rid themselves of all belongings “that come from somewhere immoral, like child labor.” He suggests they display trash bags filled with their discarded things. “That’s what Gandhi did,” he says.

The acoustics aren’t great. So GA has developed what it calls the “mic check.” When people can’t speak into a microphone, they make a statement, and the crowd repeats it en masse.

A woman objects to the idea of people throwing their clothes away. Many of the homeless people in the camp don’t have clothes to spare.

“If we burn all our clothes…” she says.

“If we burn all our clothes…” the group echoes.

“We won’t have anything.”

“We won’t have anything.”

During the night there’s a rock concert in Beta Camp and a movie about auto workers in Alpha Camp. People are passed out on the ground. A man in thick glasses reads Psalms aloud from a leather Bible in Hebrew. One man barges into the tent of another guy he says is mistreating his girlfriend; a bystander calls it “€œdrunk drama.”

Jimmy Tardy, a committee leader who helps run GA, is standing by the Medical tent around 11 pm. Tardy, a conflict-resolution specialist in his 20s with glasses and a long ponytail, shows me the tent next door, Wellness. The tent has neatly organized rows of Lipton and Trader Joe’s tea, along with a box of free condoms. The Sanitation Committee will keep working all night to bag trash and set it at the southeast edge of Alpha Camp for city parks crews to pick up at 8 am.

“What the hell’s going on here?” Tardy says. “But it’s working.”

“There’s a massive amount of tweakers,” says a young man standing nearby. “There was one guy with his shirt off that I thought was covered in body paint, but he was just sweating that much.”

“Hopefully we’ll find a way to deal with that,” Tardy says. “And if we don’t here, we’ll understand that it’s happening elsewhere.”

“If nothing else,” says the other man, “it’s a great social experiment. It’s a great thing for the people who are using it the right way.”

“I take the stance,” Tardy says, “that everybody is using it the right way.”

I wake up at 9 am Friday to the sounds of John Lennon’s “Imagine” and screams.

I brush my teeth outside my tent, since the men’s room—the old brick facility on the north edge of Beta Camp—hasn’t had running water since before the occupation. Campers have duct-taped a bottle of hand sanitizer to the front door rails, and made stall curtains from discarded Portland Marathon banners.

Over in the Information tent, more improvements are being discussed. Ethan Edwards, who wears a name tag reading “Mister Info,” is seated on a white couch with Raya Cooper—”€œMiss Info”—and Zach Parsons.

The three are putting together a plan to redesign the camp, bringing it up to fire and parks codes. They hope Mayor Sam Adams will be impressed enough that he’ll resist pressure to kick them out. They’ll present their plan to the city parks security manager this afternoon.

Edwards says Occupy Portland is creating change because it isn’t burdened by governmental rules.

“We are here illegally, so everything we’re doing—”

“We are here legally,” interrupts Parsons.

“We have permission to be here,” Cooper says.

“From the people of Portland,” says Edwards. “They give us permission.”

“I’d say the Constitution gives us permission to be here,” Parsons says, “and the people are supporting our right to be here.”

“For sure,” Edwards says.

The meeting with the city parks security manager, Art Hendricks, doesn’t go as hoped. He’s not reassuring about the legality of Occupy Portland’s stay. He says the city won’t provide help to reorganize the camp, even though Occupiers say their revised plan will do less damage to the trees.

“If you guys have plans to mitigate that [damage] as you go forward,” Hendricks says, “then God bless you.”

That night, a group of Native Americans arrive in Beta Camp to perform a drum circle. Kate Sherman brings Tupac, still in his green onesie. “If we had the weekend crowd here all week,” she says, “this would be the most peaceful, loving place.”

The vibe at the drum circle is, in fact, as genuinely happy as any I’ve experienced at Occupy Portland. Everyone is smiling. My neighbor Mario is dancing. Two men bump fists: “What’s up, Occupy?” “What’s up, 99 percent?”

Then paramedics and police part the crowd to wheel in a gurney. A teenager I’ll call Nicole sits limply on a bench in front of the Soldiers’ Monument. She’s been a presence in camp all week, wearing a pair of baggy gray sweatpants and holding a black kitten.

She says she’s been assaulted. Paramedics lift Nicole onto the stretcher and wheel her out.

The next day, Saturday, she will return to camp. She won’t want to talk about what happened. She will ask for her kitten back. Three of her friends will corner a guy in the lunch line who has a black kitten. They’ll threaten to take it by force until Nicole says it’s not hers.

But on Friday night, rumors fly through the Occupy Portland camps about what happened to Nicole. She was assaulted. She’s five months pregnant. Maybe she isn’t. She was attacked at the far corner of Beta Camp. No, she was attacked on the MAX, and came back here.

But everyone seems to agree she came back to the center of Beta Camp because it was where she knew people, and because she felt safe.