Reporter Richard H. Meeker covered Julie Christofferson v. The Church of Scientology for six weeks, during which he attended the civil fraud trial by day and served as WW’s de facto editor at night, sometimes sleeping on the floor under his desk.

The place where Meeker lived at the time was burglarized, but curiously only his notes from the trial were missing. Equally suspicious, someone drilled a small hole in the wall between the office next door and Meeker’s work area in Willamette Week’s office on the third floor of the Oregon Pioneer Building on Southwest Stark Street.

His story first appeared in the July 18, 1979, edition of WW.

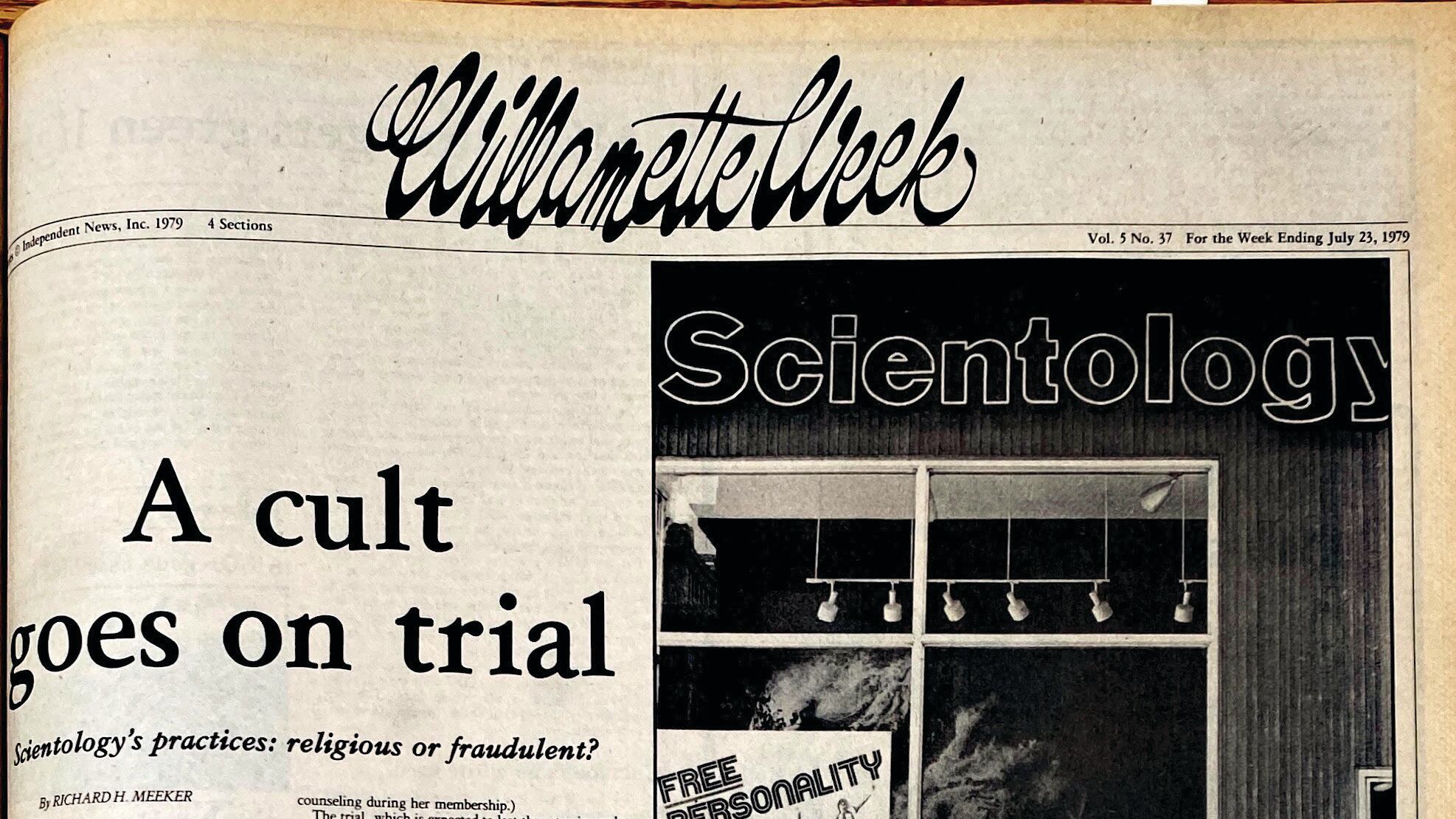

In the posh, futuristic headquarters of the Church of Scientology, at the corner of Broadway and SW Salmon Street downtown, it’s business as usual these days. The writings and teachings of church founder L. Ron Hubbard are displayed prominently; there is a constant bustle of activity; and new members continue to sign up.

Outside on the sidewalks representatives of America’s largest cult try to interest passersby in taking “personality tests,” an introduction to the self-styled religious group that promises personal improvement in return for large cash donations.

Only four blocks away, however, in the courtroom of Multnomah County Circuit Court Judge Robert Paul Jones, Scientology is on trial. In what may be the cult’s severest test to date, local church affiliates, the religion’s founder, and other Scientology officials are the target of a $4 million lawsuit which alleges that the church runs a massive confidence racket here.

Specifically, a young Portland woman named Julie Christofferson, who was a member of the cult in 1975 and 1976, says local Scientology organizations used unfair trade practices on her, deceived her and engaged in outrageous conduct in the process. By employing an Oregon statute designed to prohibit consumer fraud, Christofferson’s allegations amount to a new departure in attacking the church. If the tactic works, it is certain to be used again elsewhere.

In their defense, the Scientologists are asserting their rights to the free exercise of their religion. They say Christofferson’s complaint attacks religious practices and beliefs which are protected by provisions of the Oregon and U.S. constitutions. (The Scientologists also have interposed two technical defenses: that Christofferson waited too long to file her lawsuit and that the church offered to refund to her some $672 of the more than $3,000 she gave the church in return for training and counseling during her membership.)

The trial, which is expected to last three to six weeks, should contain a good deal of drama. First, there’s Christofferson’s story of her experiences with the cult and her charge that she was declared “fair game”—subject to severe punishment, even murder—by church members.

Second, there’s the matter of Scientology’s finances. People have wondered for years how much money Hubbard’s religion makes and where the money goes. Documents in the court file for the case indicate that extensive pretrial discovery has been allowed concerning the church’s Oregon finances. The 1976-1978 federal income tax returns of Scientology’s two top officials here have been made available to Christofferson’s attorneys, as have many of the local church’s financial records.

The Scientologists are sure to object to the introduction of this sensitive information during the course of the trial. If they are unsuccessful, the mask will come off one of the best-guarded secrets in the state.

Third, there’s the matter of the psychological effects of Scientology’s practices on its members. Critics have accused Scientology of being the most dangerous and the most mentally damaging of the modern cult groups. Christofferson’s complaint alleges severe mental and emotional distress resulting from her experiences in 1975 and 1976.

It is expected that prominent psychologists, psychiatrists and neurologists will be called to testify on Christofferson’s behalf in an attempt to prove Scientology’s harmful effects. There may be testimony to the effect that certain practices of Scientology cause permanent brain damage.

Finally, there’s the central confrontation itself: Is Scientology, insofar as it was practiced on Julie Christofferson here in Oregon, a rip-off or a bona fide religion? So long as the Scientologists are not able to prevail on their technical defenses to Christofferson’s charges, the trial should provide a definite answer to that question.

Both sides have treated this as a major case. Preparation has taken nearly two years and involved thousands of hours of lawyers’ work. As Tuesday’s trial date approached, the legal wrangling became particularly intense. On Thursday, July 12, the Scientologists asked Judge Jones to make a preliminary screening of the evidence in the trial, before a jury could hear it. They were arguing that the Constitution should prevent a jury from hearing answers to any inquiries into church practices and beliefs that are religious in nature. Thus, the defendants wanted Jones, before the trial actually got under way, to separate out all evidence that would involve the church’s religious behavior. What would be left for the jury would be evidence of those activities which Jones considered “secular”—i.e., not religious in nature.

The judge refused to grant the Scientologists’ motion, and his decision was appealed immediately to the Oregon Supreme Court. That same day Chief Justice Arnold Denecke agreed to have his court hear the matter Friday morning. Then late that afternoon the court let Jones’ decision stand; the trial of Christofferson v. Church of Scientology of Portland was set to get under way Monday afternoon at 2 pm on the fifth floor of the Multnomah County Courthouse.

Christofferson’s complaint

When Christofferson takes the stand to testify, she is expected to tell the following story:

In 1975, she graduated from Lincoln County High School in Eureka, Montana, a town of about 1,500. Christofferson, who had graduated third in a class of 72 students, and who had been considered “bright” and “personable” by her teachers, had been accepted for enrollment at Montana State University that fall. Montana State had offered her scholarship money to study architecture and engineering, and Christofferson had saved some money of her own to help defray the cost of college.

In July, she came to Portland at the suggestion of Pat Osler, a friend of hers who had been ahead of her in high school. Osler had come to Portland that spring and had joined the Church of Scientology here. Christofferson is expected to say she came here primarily to find out about Scientology—Osler had told her she could take courses here that would help her to become a better student.

Christofferson got a job doing drafting work for Detailing Northwest soon after she arrived in Portland. On July 13, she visited the Scientology Center, at the time on the second floor of 709 SW Salmon Street, across the street from the church’s present headquarters. After talking to a church spokesperson, Christofferson paid $50 and signed up to begin taking the Communications Course the next evening.

As a result of one aspect of the course—called “Bull Baiting”—the church learned about Christofferson’s “buttons”—Scientology vernacular for memories that produced in her feelings of guilt, and that subsequently were used to keep her in the church.

About midway through the Communications Course, a church worker by the name of Laird Carruthers called Christofferson in for a private meeting and talked her into signing up for two more courses and for auditing Scientology’s form of personal counseling. These courses, which had to be paid for in advance, cost Christofferson thousands of dollars and depleted her college funds. Carruthers, however, promised her she could get her money back if she wanted it later.

As all this was occurring here, Christofferson’s mother back in Montana got upset with her daughter for joining the cult. She paid several visits to Portland to try to get her daughter to drop out, but all proved unsuccessful.

Christofferson’s plan was to finish her Scientology courses by mid-September in time for the start of fall classes at Montana State. But when that time came, she had not finished her courses and went to Carruthers to see about getting her money back. Carruthers told her the money could not be returned, and that if she left, she would be considered a “suppressive person”—an enemy of Scientology. But he also told her she could go to the Delphian Foundation near Sheridan, Ore. There, Caruthers said, she could take courses that would make her eligible for college credit.

All this time, apparently, Christofferson continued to entertain doubts about the Church of Scientology and the beliefs and practices promoted in the name of its founder, L. Ron Hubbard. These doubts were encouraged by her mother’s expression of concern, and by the fact that college-level courses in architecture and engineering were not forthcoming. Instead, Christofferson was given “on-the-job training,” which consisted of babysitting and menial tasks.

But in the end, the Scientologist techniques prevailed. In her complaint, Christopherson alleges that her “ability to direct her life and form reasonable judgments was intentionally impaired by Defendants through the use of accrued polygraph, intense peer pressure and other covert means.” Christofferson became a convert.

In December, her mother returned to Portland again, this time with a scheme to kidnap her and have her deprogrammed. But when Christofferson went to meet her mother at the Hilton Hotel, she sensed something funny was going on and fled.

Her mother persisted with letter after letter and church officials at the Delphian Foundation ordered her to “handle” her mother (i.e., take care of her concerns) or “disconnect” from her. Finally, in April, Christofferson returned to Montana for one last chance to confront her mother. In Eureka, however, the tables were turned, Christofferson found herself trapped in her mother’s house—the locks had been removed from all the doors—and confronted by a deprogrammer. After spending three or four days under intensive challenging by this person, Christofferson decided to leave Scientology for good. About a year later, she filed the lawsuit that led to this trial.

Christofferson was married last year, attended Montana State briefly, and then returned to Portland, where, for the next three weeks at least, she will be a constant observer of the legal battle she initiated.

Hubbard’s cult

By including L. Ron Hubbard as one of the defendants, Christofferson’s suit goes all the way to the top of the church of Scientology. Hubbard planted the seeds of his religion in 1949 when he published what has since become a tremendous bestseller, Dianetics.

The book, which says nothing of religion, outlines what it calls the “modern science of mental health.” Its popularity and Hubbard’s teachings led to the establishment of Dianetics groups all over the United States.

For reasons that remain murky—perhaps attacks on Dianetics by the federal government in the mid-1950s—Hubbard switched his focus from mental health to religion, creating Scientology and making Dianetics the cornerstone of his so-called “science of knowing.”

Members of the Church of Scientology, who are said by the church to number about four million worldwide (three million in this country), take courses which are geared to enable them to achieve higher states of human development—known as “clear” in the church’s vernacular—as well as a form of pastoral counseling called “auditing.” In auditing, church members hold in their hands tin cans attached to “E-meters” (basically, simple lie detectors) and answer questions put to them by their “auditors.” Both the courses and the counseling are expensive, and Hubbard is said to have become fabulously wealthy from his share of the take.

In addition to suing Scientology at the top, Christofferson is attacking the church’s entire Oregon network by naming all three local affiliates as defendants. Included in her lawsuit are the Church of Scientology of Portland, at 333 SW Park Ave., and its president, Dennis Patton; and the Church of Scientology, Mission of Davis, both downtown at the corner of Broadway and Salmon Street and at the Delphian Foundation in Sheridan, Ore.; and Martin Samuels, president of the Mission of Davis. (Samuel’s Mission of Davis also has three branches in California, in Davis, Sacramento, and San Francisco.)

The role of the Delphian Foundation in the church’s Portland-area activities should make for particularly interesting questioning at the trial. Since its founding on the site of a beautiful Jesuit novitiate southwest of Portland in 1973, the foundation has maintained that it is a nonprofit educational institution with no ties to the Church of Scientology. Yet, Samuels has been the head of the foundation since 1974, and Scientology is practiced by those in residence there.

Lawyers

In a major lawsuit like this, the role of the lawyers who will be trying it becomes particularly significant. Christofferson v. the Church of Scientology pits two of Portland’s best trial lawyers against each other.

Representing the Church of Scientology and the other defendants is Jack Kennedy, a partner in the firm of Kennedy, King & McLurg and president of the Oregon State Bar. “I have no interest one way or the other as a personal matter,” Kennedy says of this case. “I’m representing a client who’s entitled to be defended. It isn’t as black and white as it’s been painted.” Beyond that, he will offer no other comments.

Kennedy’s opponent is Garry P. McMurry, a one-time law partner of U.S. Sen. Bob Packwood, and a member of the firm of Rankin, McMurry, Osburn, Gallager and VavRosky. Where Kennedy is taking a quiet, conservative approach to the case, McMurry, 10 years his junior at 45, should be the aggressor.

“These lawyers are well suited to their clients’ needs,” says a colleague of both. “Kennedy is as competent a trial lawyer as you’ll find in Oregon. He thinks. He’s clever. He’s diplomatic. And he’s quite insidious, because he doesn’t signal his shots.

“McMurry is nowhere near as experienced. But he’s charming. He’s an attractive human being. He speaks well. In sum, he’s a personable trial lawyer.”

Julie Kristofferson’s lawsuit against the Church of Scientology is by no means the only legal action pending against the church. On Sept. 24, in Washington, D.C., the U.S. Justice Department should begin to put on evidence its criminal action against the church for stealing government property, obstructing justice and illegally eavesdropping. L. Ron Hubbard’s daughter, presently one of the church’s highest officials, is among the 11 defendants in the case. Hubbard himself is not charged in the indictment.

Then, according to a June 14 article in the Los Angeles Times, in Riverside, California, “Sheriff’s deputies seized 17 boxes of documents from the Riverside mission of the Church of Scientology Wednesday [June 13] in a search for evidence that possibly as many as 100 past and current members fraudulently obtained bank loans and then gave the money to Scientology.

“Riverside Sheriff’s Capt. Jack Reid said authorities have no idea how much money may have been fraudulently obtained,” the article continued. “But there is reason to believe he said some loans as high as $10,000 were obtained by Scientologists, by making allegedly false financial statements—subsequently verified by church officials—on loan applications to banks and finance companies.”

While all this legal activity is gearing up elsewhere, Scientology’s most significant challenge is being advanced here in Portland in Judge Jones’ courtroom. Two technical defenses stand between the church and a full-scale trial. First, the Scientologists say, Julie Christofferson let the statute of limitations run on her unfair trade practices claim. That is, she waited for more than a year after she was deprogrammed to file her suit, and the statute allows only one year. Christofferson is expected to testify that the effects of Scientology did not wear off as soon as she had left the organization.

Second, the church says it offered to repay to Christofferson some $672 of her donations and therefore need not compensate her under the Uniform Trade Practices Act. Christofferson is expected to say the repayment offered was insufficient.

If the Church of Scientology is unable to prevail with either of these defenses, the next three to six weeks should provide the public with the closest view so far of one of this era’s most successful and secretive cults.

Afterword: The plaintiff’s high-powered attorney, Garry McMurry, won a handsome verdict against the church at trial, but appeals dragged on for almost six years, at which point a verdict of $39 million was finally thrown out when the presiding judge declared a mistrial. Meeker went on to become Willamette Week’s co-owner and publisher in 1983.