The Portland City Council would never have another city commissioner quite so implacable to bureaucrats and beloved by her constituents as Mildred Schwab, profiled here by Willamette Week’s most perceptive profiler of certifiable characters, Susan Orlean. This story first appeared in the July 27, 1981, edition of WW.

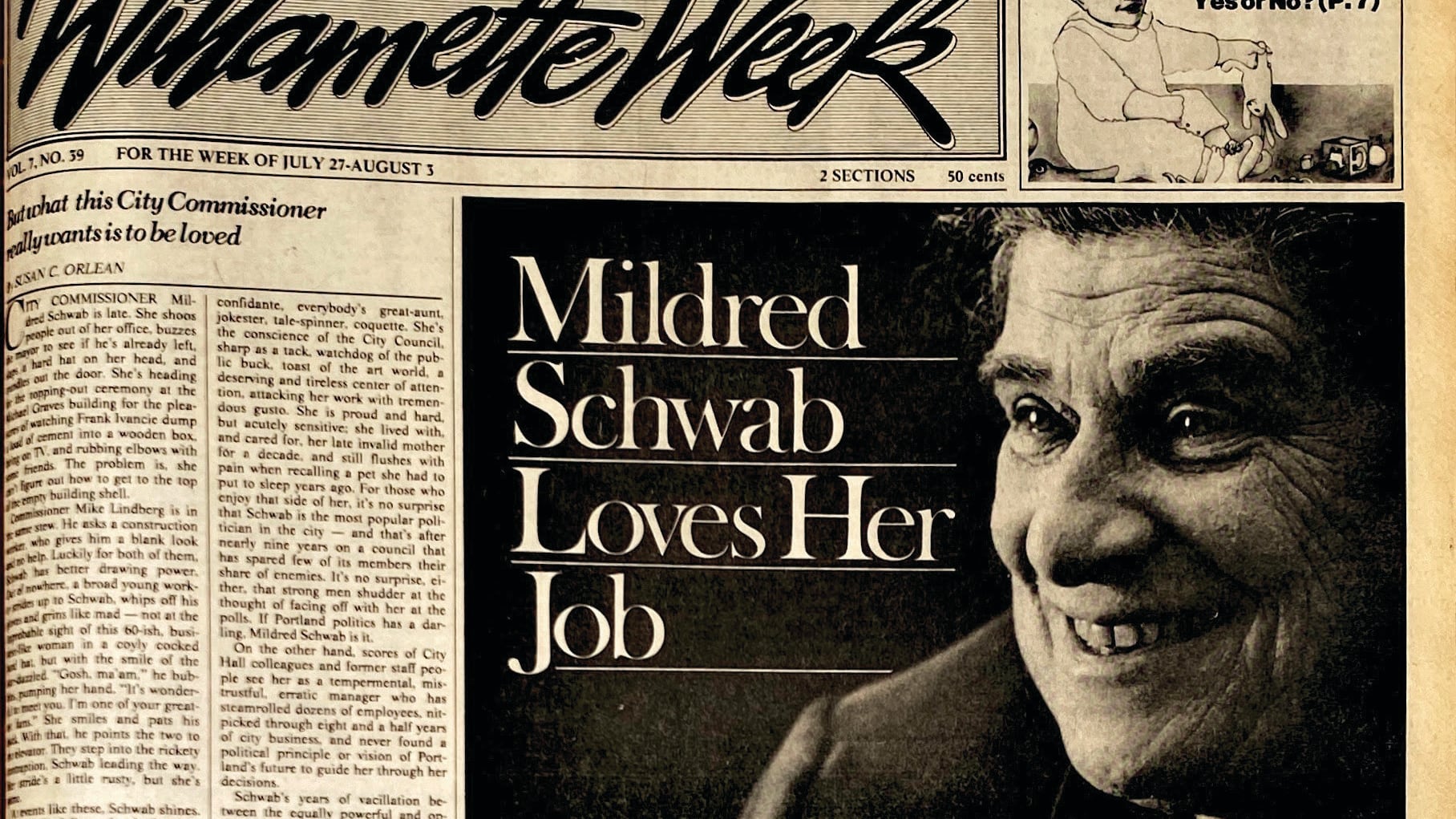

City Commissioner Mildred Schwab is late. She shoos people out of her office, buzzes the mayor to see if he’s already left, slaps a hard hat on her head, and trundles out the door. She’s heading for the topping-out ceremony at the Michael Graves building for the pleasures of watching Frank Ivancie dump a load of cement into a wooden box, being on TV, and rubbing elbows with some friends. The problem is, she can’t figure out how to get to the top of the empty building shell.

Commissioner Mike Lindberg is in the same stew. He asks a construction worker, who gives him a blank look and no help. Luckily for both of them, Schwab has better drawing power. Out of nowhere, a broad young worker strides up to Schwab, whips off his gloves and grins like mad — not at the improbable sight of this 60-ish. business-like woman in a coyly cocked hard hat, but with the smile of the star-dazzled. “Gosh, ma’am,” he bubbles, pumping her hand. “It’s wonderful to meet you. I’m one of your greatest fans.” She smiles and pats his back. With that, he points the two to the elevator. They step into the rickety contraption. Schwab leading the way. Her stride’s a little rusty, but she’s game.

At events like these, Schwab shines. Ivancie will deliver the boilerplate dedication speech, and emcee; architect Michael Graves will be the special guest; builder Eric Hoffman and financier Bill Roberts will win acclaim for a job well done. But it’s Schwab who’ll be pressing flesh and cracking sly jokes, who’ll be passed from admirer to admirer. Everyone else fades into the background as she gathers compliments on her newly slimmed-down figure, trading winks and gossip with the guys. She’s in her element, surrounded by people who think she’s great.

She’s not power hungry, propelled by principles, or driven by a passion to mold the city to her liking. She simply wants to be the best at what she does, and to be loved. Above all, loved. All the seeming contradictions of her personality are glued together by that fierce desire.

There are people around her who believe that the charming exterior is all there is to Mildred Schwab: friend. confidante, everybody’s great-aunt, jokester. tale-spinner, coquette. She’s the conscience of the City Council, sharp as a tack, watchdog of the public buck, toast of the art world, a deserving and tireless center of attention, attacking her work with tremendous gusto. She is proud and hard, but acutely sensitive; she lived with, and cared for, her late invalid mother for a decade, and still flushes with pain when recalling a pet she had to put to sleep years ago. For those who enjoy that side of her, it’s no surprise that Schwab is the most popular politician in the city — and that’s after nearly nine years on a council that has spared few of its members their share of enemies. It’s no surprise, either, that strong men shudder at the thought of facing off with her at the polls. If Portland politics has a darling, Mildred Schwab is it.

On the other hand, scores of City Hall colleagues and former staff people see her as a temperamental, mistrustful. erratic manager who has steamrolled dozens of employees, nitpicked through eight and a half years of city business, and never found a political principle or vision of Portland’s future to guide her through her decisions.

Schwab’s years of vacillation between the equally powerful and opposing forces of fellow commissioner Ivancie and then-Mayor Neil Goldschmidt was less a cagey political scheme than her fervent wish that both of them should like her. Wanting to be liked, not wanting to make enemies. and taking it all personally explains most of the contradictions in this proud, intelligent, hard-working woman: the gregarious fun-lover who lives alone, the astute politician without politics, the compassionate friend with the stormy temper, the brilliant lawyer who can’t seem to make up her mind.

She lives alone, spoils her dog, hobnobs with her neighbors. And she loves her job. She barely ever misses an official function, is in her office by 7 am, eats dinner several times a week at a fire station now that she handles the Fire Bureau. She loves to argue, and finds ample opportunity for that at council meetings. She loves the limelight after so many years behind the scenes.

Her seat is open in 1982. She’ll be 65 in January — about when she’ll have to start raising money to run again, if she runs again. She’ll make the decision within the next few weeks, she says.

“I figure I’ll leave when it suits me,” she smiles. “There is a time to start and a time to finish. It’s hard, though, to think you might be closer to the time to finish.”

Don’t count on it, say her friends. She’s been grumbling about leaving politics for years, but she’ll never quit. She takes it all to heart too much to give it up.

I have a photographic memory, so I used to just memorize what the teacher read and read it back. One day she asked me to read the next page, and I couldn’t, and she figured out that I couldn’t read. That weekend, my brother taught me to read. I was 6 years old. Herb used to beat me up if I didn’t do well in school.

Mildred Schwab was born in Northeast Portland on Jan. 9, 1917, the second and last child of Gustav and Frances Schwab. He was a wholesale clothing salesman, a German Jewish immigrant; she was bossy and strong-willed.

“God forbid that anyone call Mildred ‘Mildy’ around her mother,” laughs an old friend “It was Mildred Ann or it was nothing.” They were, Schwab says, quite poor, loosely religious, and smitten with education. Mildred Ann made the math team at Grant High, but inspired no nickname or flip anecdotes next to her graduation picture in the 1954 yearbook. Her older brother, Herbert, had just entered law school, and convinced his sister to follow him. They both worked their way through night school at Northwestern College of Law (at the time, you didn’t need an undergraduate degree to study law). At the same time. Mildred, a promising young classical pianist, was studying with J. Ariel Rubstein at the Portland School of Music. Still, she speaks enviously of her brother’s accomplishments.

“He did so well in school.” She punctuates it with a shrug. “He was a hard one to follow. They always expected too much from the one behind.”

In 1939, Schwab graduated and was admitted to the Oregon Bar — one of only two women admitted that year. She might have gone on to be a concert pianist, but she chose to stick with law, working on her own for a few firms. Her clients included Rubstein’s Celebrity Attractions, the local impresario, and Simon Director, a large downtown property owner and patriarch of one of Portland’s leading Jewish families. A woman lawyer when it wasn’t in vogue to be one, she made her mark from her tiny downtown office. Legend has it that Director wouldn’t answer the phone without consulting her first.

In 1950, Gustav Schwab died of a heart attack while away on a business trip. For the next nine years, Mildred and her invalid mother shared an apartment: after her mother’s death in 1959, Schwab bought the home where she still lives today, a brick-red, hill-hugging bungalow in Northwest Portland.

A few years later, she met a young political bird dog named Frank Ivancie. He was then-Mayor Terry Schrunk’s assistant and she was hanging tough on some deals for the Directors.

“I thought she seemed like an able person,” Ivancie remembers, “and a hard bargainer.” In 1970 he launched her public career by getting her appointed to the Planning Commission. She wouldn’t be the first Schwab in the public eye: by then, Herbert Schwab had served prominently on the Portland School Board, written the influential Schwab Report on Desegregation. and was heading for a judgeship on the state Court of Appeals. He was always a hard one to follow.

I never considered going into politics, and I didn’t apply for the position. The council had run through about 200 names, trying to find someone they could agree on to fill Neil’s seat when he was elected mayor. I was sitting in my office when Ivancie called me and asked me to be his nomination. I said I’d think about it. Then a few minutes later, Neil called and asked me to be his nomination and I said I’d think about it. When Lloyd Anderson called after that and asked me to be his, too, I decided I’d try it for a year. It look about three months before I decided I liked it.

It was Dec. 14, 1972. Le Duc Tho had just walked out of the Paris peace talks. Neil and Margie Goldschmidt had just had a baby, and Mildred Schwab had just ended her 32nd year as a lawyer, and was appointed to the City Council. She’d also cemented her reputation as a first-rate party giver, holding lavish receptions for artists after their performances in town. Van Cliburn was a close friend: occasionally, she’d travel with him for a few weeks while he gave concerts. Even now, over her desk hangs a faded photo of one of her classic parties — filet mignon at midnight, Cliburn, Tom McCall, and a cake like a tiny piano. Peering shyly at the proceedings is Mildred, by then a sturdy boat of a woman but with the slim ankles of a girl.

She became a commissioner. Before her appointment, she promised Goldschmidt that she would vote against the Mt. Hood freeway and the Northwest Portland freeway extension. Then she could fly on her own wings. But, throughout Goldschmidt’s tenure as mayor, she was torn between feeling obligated to him for appointing her and being afraid he was manipulating her. It became a point of pride for Schwab to prove she wasn’t a Goldschmidt lackey.

Her style emerged almost immediately: when Goldschmidt didn’t assign her any major bureaus, she spent her time reading every inch of ink on every issue coming before council, and then asking questions no one could answer. Exasperated, Goldschmidt gave her several projects to keep her busy.

“She has,” remarks Cliff Carisen, a lawyer with Miller, Nash, Yerke, Wiener, and Mager who served as city attorney under Schwab, “a tremendous ability to tick people off because of her persistence. She really goes after the nitty-gritty.”

Sometimes the nitty-gritty wasn’t enough. Never having managed people before, Schwab was thrust into the difficult dual role of a Portland city commissioner, that of a legislator and an administrator. Even her closest supporters agree that administration is a difficult tangle for her, chaotic and emotional. Among her first assignments was the city attorney’s office. which she piloted smoothly, counting on her lawyer’s instincts. Rockier was her tenure with the newly formed Human Resources Bureau, although she still counts the Youth Services Centers (one of her projects with that bureau) among her favorite city accomplishments. Unlike most commissioners, who lay down general principles and policies and back off from the nuts and bolts of their bureaus, she offered little in the way of philosophy but wanted her hand in every minor move. After so many years as boss of her own show, she had trouble knowing how to let go.

“It was insane.” recalls a bureau manager who worked under her. “It was like a very long, peculiar dream. She had no management experience. She thrived on crisis, and created it. One minute she’d be totally supportive, then the next, she’d cut out from underneath you.”

Schwab’s staff felt the rumbles, too. She didn’t like them to be too chummy with each other, or with the other commissioners’ staffs.

“As much as she mistrusted her staff, she mistrusted Neil’s even more,” says Paul Linnman, who served as Schwab’s executive assistant for five years before joining KGW-TV. “There was no feeling of camaraderie at all in the office. She divided people up and assigned them their tasks. Mildred was never good at those staff bull sessions that Neil was having down the hall.”

Part of her problem, apparently, is being too smart. She constantly caught small errors in staff work — zeros in the wrong column, bad addition, unsound arguments. Coupled with her dread for being embarrassed in public, it became a full-time job to keep tabs on her staff. Lying and surprises are two things she really hates. Loyalty, too, was a paramount concern. When another commissioner voted against her. Schwab would sometimes take it so personally that she would insist that her staff end all communication with the offending party and staff. She wanted to know about everybody’s phone calls and visitors and mail.

Naturally, her style drove away staff people, and she became known as the commissioner with the revolving door. In fact, her executive assistants have been fewer than Goldschmidt’s, and have the record for longevity in City Hall, with Linnman’s five years and Tony Reser, who still works for Schwab, approaching his fifth.

“She is difficult and demanding — the hardest person I’ve ever worked for,” Linnman says. “But she really respects someone who’ll yell back at her. That’s what I really like about her. It was amazing — we disagreed a full 100 per cent of the time. I used to think, just how long is this woman going to allow me to disagree with her? Then I stopped wondering, because I knew that she accepted that we disagreed.”

Schwab sees turnover in her office as a healthy sign, proof that she’s hired people bright and ambitious enough to move on to bigger and better things. She’s proud of her former assistants’ accomplishments, like Linnman’s television job, Loren Kramer’s executive position with Schnitzer Steel, Jayne Carroll’s consultant business. When another assistant of hers, Jamie Mart, kept returning to work for her and dawdled about going to graduate school, she agreed to hire him again only with the promise that he really would leave for school after a few months. Former staff members recall Schwab’s reacting to problems by exploding, exploding again, and then maybe talking it out; she’d rip them up one side and down the other for mistakes, but she’d take an avid interest in their personal welfare, their families, their troubles.

She’d lean all over Mike Lindberg when he was a bureau manager for then-Commissioner Connie McCready, with whom Schwab didn’t get along, but consoled and counseled him through his divorce. Embittered though some might be by her bluster, impatience and mistrust, few of her former staff members can shake the memory of the time she tried to be a friend.

Why do I like Mildred? I was young, just out of law school, arguing my first time before City Council. Boy, was I nervous! There were television cameras and reporters and the chambers were packed. At the break, Mildred came up to me and said, “You’re new in this business, aren’t you?” I said yes. and she said, “Don’t worry, kid, you’re doing fine.” Then she told me a joke about a priest, a rabbi and a lawyer in a sinking boat encircled by sharks. The rabbi and priest dive off and barely make it to shore. Then the lawyer dives in, and swims leisurely, and the sharks just line up and let him pass. Why? Professional courtesy.

—Steve Janik, lawyer

Schwab’s days are filled with the grandest and pettiest of tasks. This morning begins with a meeting about the Performing Arts Center. She’s cooking up a way to raise a few million dollars.

“Don’t worry,” she assures the committee members. “That’ll be no problem. It’ll be the five brilliant minds that make up the council that’ll give you the hassle.” Wink. grin, tug on her ever-present Tareyton. Her voice has the rich rumble of a rock polisher, crusty with the soot of nonstop smoking.

Later, a fire fighter stops by to get her signature on his leave-of-absence form. In most commissioners’ offices, an assistant could initial this routine paperwork; in Schwab’s fiefdom, nobody but the commissioner signs anything. The fire fighter is shy and deferential and can barely squeeze out an answer when she asks him where he’s headed. She’s especially fond of the Fire Bureau — she goes to many of the big fires, had Christmas dinner at one of the stations, lunches regularly at different stations each week, cooks dinner on occasion for “the fire boys.” It’s also nicely noncontroversial, which suits her fine.

This afternoon’s council session it pretty peaceful stuff: mostly restaurateurs wrangling with homeowners about parking lots. Commissioners Charles Jordan and Margaret Strachan are absent, Lindberg is eating cheese and crackers and peanuts. Ivancie is playing with his tie. Schwab is performing in a subdued form of her sharp prosecutorial style.

“Sometimes,” Ivancie remarked earlier in the afternoon, “I like to set her off a little, especially on a slow day.” Today isn’t one of them, though it’s slow. And Schwab certainly can be set off. Only a few months before, The Oregonian, usually prone to support her, ran a stinging editorial criticizing one of her outbursts, in which she needled and bullied citizens testifying about a recycling center. She claims to reserve those tactics for her lawyer friends, with whom she relishes the verbal battle.

She has a fine-tuned concern for wasted public dollars and sloppy government work: her political role has been circumscribed by that and her interest in the arts. She’s also sincerely pleased to pick up the phone once in a while to solve a small problem for someone. She’s not known for her innovation or her creativity in governing: in fact, say former staffers, she’s so loath to risk making a mistake that she’d just as soon not propose much of anything.

Since 1977, her most important assignment has been running the city’s Parks Bureau. By all accounts she’s loved it. With its 7,000 acres of park land, 72 playgrounds, 13 community centers and vast recreation programs, Parks was an ideal bureau to have. It’s all tree-planting ceremonies and kicking soccer balls at the Timbers’ Opening Day and none of the nasty, fractious politics of the Police Bureau or Planning.

In January 1980. Doug Bridges, who had run the bureau since April 1977, resigned. A lot of people say Schwab forced him out, tired of his ambitious plans for expanding the parks system, his chasing of federal dollars and his willingness to go around Schwab to solicit Goldschmidt’s backing for his ideas. There was also what she did (or didn’t) do to help the city’s first parks levy in 10 years, a $120 million parks improvement voted on in May 1978. The levy was a shoo-in, or so Bridges was told when he was being wooed by the city. But it failed by a healthy margin. The supporting campaign started late, was disorganized, and got only lukewarm support from Schwab, who was in the middle of her own campaign and was afraid to champion an issue that might lose her some affection — and votes. Instead, her hopes for Portland’s future are safely fuzzy — preserve the neighborhoods, promote the arts, protect free services.

“Actually,” she says, “the most fortunate thing about Portland is we’re 10 years behind everyone else. In some things you’re better off being a little slow.”

How does she arrive al her decisions? Most observers assume she takes direction from her two closest friends, her brother and Ariel Rubstein.

“We don’t talk politics,” Rubstein says flatly. “I don’t like politics. I don’t like politicians.”

Her brother is just as outspoken. “Wrong. We’re good friends. But I almost never know what she’s going to do. And I don’t think she looks to anyone for advice.” Certainly, she doesn’t rely on her staff to digest information and feed it to her. It’s one thing, she says, to know things firsthand, and quite different to know them secondhand. She, for one. doesn’t intend to head downstairs to Chambers and get caught not knowing something.

I don’t have as many parties any more, but when I leave here. I’ll have more I love having them. My favorite party was when I invited the Portland Timbers and the Joffrey Ballet for dinner. There were 90 of them. People thought we had a wild evening.

She’s run twice: once with virtually no opposition in 1974, and in 1978 against Arnold Biskar, an accountant and a relative newcomer to the city. At the time, she was widely known and had a hefty war chest, a panoply of supporters, and few identifiable enemies. Biskar’s rallying point was Schwab’s obvious lack of political philosophy. He received support from several of her colleagues on the council, but in the wider community he kept hearing, “Come back when you’re running against someone other than Mildred.” Biskar received some important endorsements — including those of the Oregon Women’s Political Caucus and the Oregon Journal — and Schwab got her picture in the paper, planting a tree, playing with her dog, or just being in the right place. She ended up pulling in over 60 per cent of the votes.

Something surfaced during the campaign that left lingering suspicions about Schwab: Biskar filed a complaint with the secretary of state’s office, charging that she had used " undue influence” to intimidate city employees who were working on his campaign.

“Mildred can be vindictive,” says a former staff member, “and even though she had no reason to be, she was terrified of Biskar.” At Biskar’s request, the complaint remained open for a year after the election, but was finally closed when evidence to support it never materialized.

Vindictive? Maybe. Ironically, Schwab recently recommended that Biskar be reappointed to a commission she chairs. She also spends 16 hours a week in Chambers sitting next to one of the parties named in the complaint, Margaret Strachan.

She used to talk about running for mayor, and a lot of Schwab supporters are sorry she never did. Close friends say they’re glad, that the race would have been hard on her, that it would have made her too vulnerable.

“She doesn’t need that kind of grief,” says Carisen, who ran Schwab’s campaign against Biskar. “Mildred is much more sensitive to criticism than people who’ve been in politics all their lives.”

Schwab shrugs it off. “If you go for mayor, you can’t help but stir antagonism. Nobody’s invulnerable to that. You must have a pretty thick skin if it doesn’t bother you.” She pauses. “You’d have to be a pretty inhuman person.”

She’s so proud that now that time has taken the edge off her fine piano playing, she won’t perform for anyone. No one else would hear the difference, but she knows it and that’s bad enough. Her beloved dog. Blitz, is old now, and those long beach walks outside her condominium in Lincoln City are less frequent. If she doesn’t run again, she’ll travel to Europe. then begin another career. She’s had a few tempting offers but she won’t say what they are.

Many of Schwab’s friends think the rich patchwork of her many interests barely covers a life that’s essentially lonely. She has a different version.

“My greatest accomplishment is that I enjoy my life. My brother taught me that — enjoy your life.”

Says her old friend Frank Ivancie, “Mildred enjoys being Mildred. She may not know it all the lime, but it’s true.”

Schwab retired from the City Council in 1987 and died in 1999. Orlean was a staff writer at WW from 1978 to 1982, moving on to write for The New Yorker and to author such books as The Orchid Thief (Meryl Streep played her in the film adaptation) and The Library Book, about the 1986 fire at the great Los Angeles Public Library.