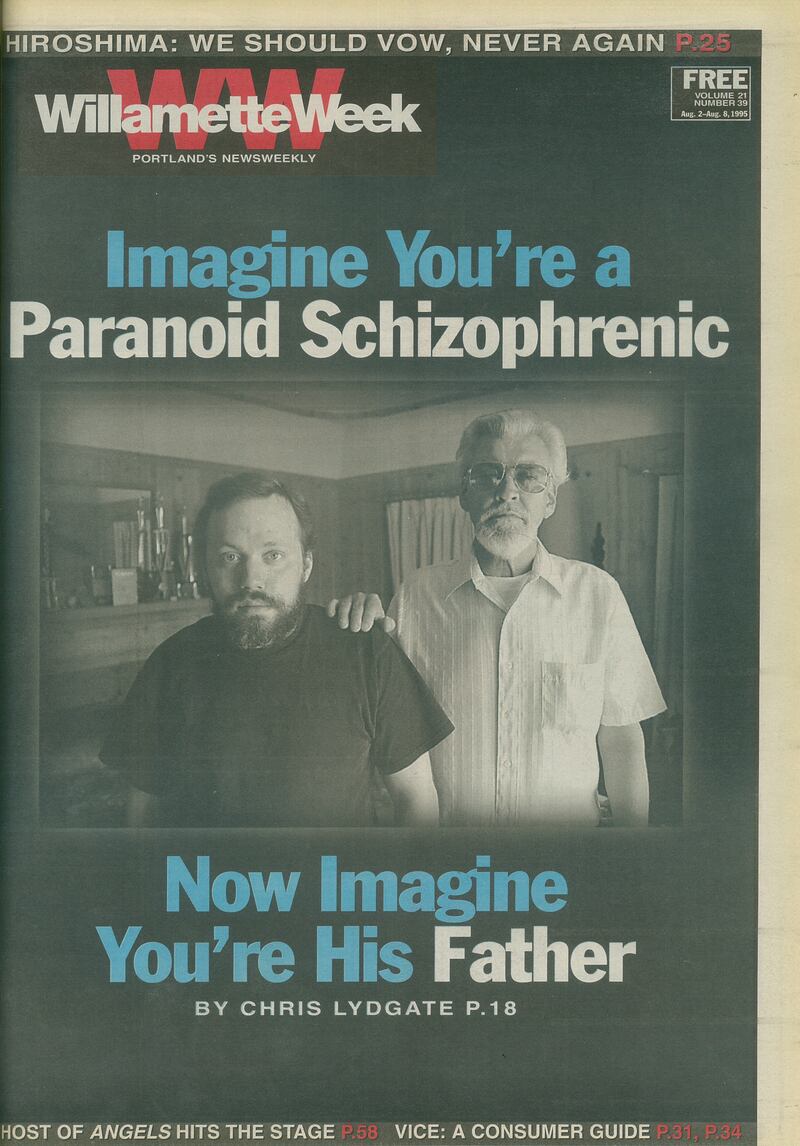

Staff writer Chris Lydgate applies his signature empathetic writing style to this moving portrait of Denny and Brent Olson, a father-son duo forever bound by Brent’s debilitating struggle with paranoid schizophrenia, a struggle that had inexorably taken over virtually every aspect of his father Denny’s life. This story first appeared in the Aug. 2, 1995, edition of WW.

Denny Olson lives in a pleasant house on 3 1/2 acres in the outskirts of Tigard. His porch overlooks a quiet expanse of soaring maples and honey locusts. He’s got plenty of time to enjoy the view; at age 55, he recently retired from a long career in the high-tech business.

Denny Olson is miserable.

In the past three years, his son Brent, 29, has been arrested five times, spent several months in jail, visited dozens of hospital emergency rooms, and been involved in a number of assaults. He has been thrown out of group homes. He has wandered the streets of Portland and Seattle, without a job or a home.

Brent is a paranoid schizophrenic. And he’s his father’s burden.

After years of trying to help his son, the strain is finally showing. Denny has problems getting up in the morning. He doesn’t get out much. He’s beginning to let parts of the house go to seed: Hooks and boxes clutter the upstairs landing. “Excuse the mess,” he sighs. “I just don’t care about it anymore.”

Friends and family have watched Denny’s struggle with concern. “He’s tried to help out, but it’s like banging your head against a wall.” says Butch Vose, Denny’s brother-in-law. “He never takes a vacation. He can’t go anywhere. He doesn’t see any light at the end of the tunnel. I would have given up a long time ago.”

Roughly 30,000 Oregonians suffer from schizophrenia, a disease so devastating that an estimated 10 percent of its victims eventually commit suicide. Contrary to popular perception, the disorder has nothing to do with having a “split personality.” With schizophrenia, the mind is not split so much as splintered, bombarded by hallucinations, unable to concentrate for long or to distinguish imagination from reality.

While many schizophrenics can lead normal lives if they take their medication, some never get their symptoms under control. These are the Brent Olsons of the world, who skid in and out of reality, see-sawing between dazed inaction and frenzied paranoia. In the past, they faced lifetimes locked up in mental institutions, but that’s no longer the case. The emphasis in mental health care has shifted nationally to community treatment, as evidenced last month by the closure of Dammasch psychiatric hospital. Now these unfortunate people wander the streets of major cities, sometimes almost sane, sometimes dangerously unstable. Behind many of them is a guardian, a sibling or a parent who carries the unenviable and sometimes impossible burden of trying to help their loved one.

Like most parents of kids who show evidence of abnormal behavior, Denny Olson spent many years stuck between feeling that he was worrying too much about his son and that he should be doing more. This uncertainty was fueled by Brent’s situation: He was not Denny’s biological son but was adopted at birth. When Brent was 5, his adopted mother, Denny’s wife, died of Hodgkin’s disease. As a result, Denny was alone to confront Brent’s recurring nightmares and increasing isolation. Were these serious problems or passing phases? “As a parent, you never want to think there’s any kind of problem,” Denny says. “You excuse it by assuming he’ll grow out of it.” In the meantime, he spent as much time with his kids as he could, taking them camping and teaching them to race motorcycles.

Brent was a good student, and when he graduated from Beaverton’s Sunset High School in 1984 and signed up with the U.S. Navy, Denny felt a mixture of pride and relief. “I was glad he was going to do something meaningful with his life,” Denny says.

The first signs were promising: Brent went through boot camp, enrolled in the Navy’s nuclear power program, and was stationed in Orlando. But in 1986, Brent got kicked out of the service for drinking onboard ship. Denny chalked it up to a typical teenage rebellious streak, though by now Brent was 20 years old. “He was still forming his opinions and values,” Denny says.

The problems seemed to get worse. Shortly after Brent left the Navy, Denny got a call from the Las Vegas city jail. It was Brent, serving 90 days for shoplifting.

After he got out of jail, Brent came back to live with his dad and got a job pumping gas at an AM/PM. Denny pushed his son to get a better job and get his life together, while Brent spent his time lying around on the couch listening to punk-rock records. It was not an atypical scene; nevertheless, an uncomfortable feeling began gnawing at Denny.

Then, one morning in the summer of 1988, he finally knew something was wrong when he found Brent sitting in his darkened room with the drapes drawn, muttering to himself There was a demon inside him, Brent said, and he needed an exorcism.

Dressed in a black T-shirt and black shorts, Brent appears mild-mannered, with uncombed hair and a thick beard covering his acne-scarred face. When he stands, his arms hang awkwardly, as if suspended from an iron rod running from shoulder to shoulder. His blue eyes hold a steady, districted gaze, like he’s watching a television no one else can see. Sometimes he will sit for hours without a word.

When he does speak, Brent resembles a record player with fuzz on the needle. He never really seems to get in the groove, constantly skipping to other topics or repeating the same thought over and over “Now, I’m really against democracy,” he says, dragging on a Newport menthol. There is a slight pause, then he adds, “Sort of. Well, it depends… I’m against uniforms in schools.” In short, he is against a great many things: base closings, more cops on the streets, carbon testing, the Ice Age.

A few months alter the exorcism incident, Brent moved up to Seattle to try to start a band. That’s when the voices regularly began to crowd his head, screaming obscenities no one else could hear. “I thought it was the devil,” he says. “I thought the voices came because I blasphemed the Holy Spirit.”

The illness tore through the fragile fabric of his life in Seattle, which consisted of a sodden mixture of booze, pot and angry music. He was convinced someone had put a curse on him and that he had been sodomized by the evil spirit inside him. Eventually he wound up in a Tacoma hospital. “I thought there was going to be an earthquake,” he explains. “I thought Tacoma was going to be consumed by a tidal wave.”

Brent’s sister Sandy (who was also adopted) drove up to Tacoma and brought him back home, and in January 1989, Denny was finally able to persuade Brent to see a psychiatrist in Cedar Hills. Brent was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia is one of the most puzzling and devastating disorders known to medical science. Symptoms include delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking, odd behavior, a narrowing of emotional expression, and a tendency not to talk much or interact with other people. (In the paranoid subtype, the delusions and hallucinations are more pronounced and organized around a particular theme—in Brent’s case, demonic possession.) It strikes roughly one person in a hundred across all cultures, usually emerging, sometimes overnight, in the mid- or late 20s. No one knows what causes the disorder, although it seems to have a genetic component. Some patients respond well to anti-psychotic drugs such as stellazine or clozaril. For others, like Brent, the medication may flatten out the extremes but otherwise have little effect. Sometimes the disease is so resistant to treatment that the only recourse is to remove schizophrenics from society, in order to minimize the risk of hurting themselves or others. “There’s treatment but there’s no cure.” says Dr. George Keepers, director of the psychiatry program at Oregon Health Sciences University. “It’s a severe, disabling illness, and people who get it have a lifetime of disability.”

The diagnosis came as a shock to Denny, but at the same time, it explained a lot. “I looked back and I realized the things in his childhood that were different,” he says. “I felt like an ass for not being more sensitive.”

Brent didn’t want to go into a group home. With medication, however, Brent was able to reduce the severity of his symptoms and function after a fashion. He lived at home and attended Western Business School, where he graduated with a GPA of 3.6. Then he got a job as a night clerk at the Travel Inn in a run-down section of East Burnside, and moved into his own seedy apartment.

Even these small achievements vaporized as the disease pulled Brent down. He lived with a hooker (whom he says he beat up several times), lost his job and his place, and was arrested twice for assault. Every time his life unraveled, he called on his father to pick up the pieces. Altogether, Denny helped him clear his stuff out of three different apartments “Each one you wanted to clean up with a match and a gallon of gasoline,” he says.

Like many men of his generation, Denny Olson is sparing in his display of emotion. Sitting in his driveway, smoking his Newports, he keeps his voice steady as he recounts his son’s horrifying episodes of the past 10 years—the violent outbursts, the telephone calls from jail, the midnight visits to the emergency room, the court dates, the appointments with doctors, counselors, and probation officers.

Despite worsening symptoms, Brent refused to enroll in a program or go to a group home, getting angry if Denny even raised the subject. In January 1993, their disagreements came to a head. Brent asked his dad to drive him to a local church so he could perform an exorcism on himself. When Denny refused, Brent exploded, threw a glass milk pitcher filled with knives in his father’s direction, and stormed out the back door. Denny called 911. Later, police found Brent wandering the streets of Tigard with an unloaded .45-caliber Ruger he’d stolen from his dad.

At times the mental health system seemed as irrational as his son. A few days later, Denny tried to get Brent committed to a mental hospital. He thought the chances were good. After all, his son was clearly deranged and needed help. But that didn’t seem to matter at the court hearing. To be committed, a person must be imminently dangerous to himself or others or unable to take care of his own basic needs. The judge asked if Brent knew how to find food, shelter and clothing. Brent insisted he could make money by selling matches on the streets of Portland, get meals at Baloney Joe’s, and sleep under a bridge. The judge released him. Afterward, father and son walked out of the courtroom through separate exits. They passed on the sidewalk without making eye contact.

Brent dropped out of sight after that but turned up in Seattle. Denny heard from him occasionally. He was down and out, bouncing in and out of missions, shelters and group homes. “I worry about him.‘’ Denny wrote in his diary. “I don’t know how long he can continue like this.”

Then, on a warm evening in September, Denny heard the front door open and footsteps coming through the dining room. It was Brent.

“Hi, Dad,” he said.

Denny hadn’t seen his son in more than a year, and he felt his heart sink as he cast his eye over the stranger in front of him. Brent was a sorry sight, dressed in ratty thrift store castoffs, his gnarled beard halfway down his chest, his long hair matted and unruly. Some notepads and a few old clothes—everything he owned in the world—were stuffed into a battered suitcase with a broken zipper. His clothes were crawling with lice. And he stank. “I’d rather smell a rabbit hutch!” Denny scowls.

Brent said he just wanted to sleep on the couch for a few days. Mental-health workers had told Denny not to let Brent come back until he was willing to seek help for his condition. Easy advice to give.

He thought of how Brent had struggled on his own and all the times he had worried if his son was all right. “Every time I’d pick up a paper and read about an unidentified body they fished out of the river, I’d think, ’It’s only a matter of time,’” he says. “Can you imagine what that’s like?”

Denny fixed something for them to eat. He decided he could handle it for a few days. And he would try to get his son into some kind of group home one more time—that was the least he could do.

After Brent had been sleeping on the couch for a week, Denny finally talked him into going to the hospital to be examined. On Oct. 10, they went to OHSU. The examining psychiatrist was anything but reassuring: The best they could hope for, he told Denny, was for Brent to hurt someone. Then the police could step in and take him to jail, where he could get medication and some psychiatric attention. Reluctantly, Denny decided to turn in his own son.

Because Brent never showed up for the trial on charges arising from the gun incident, the judge had issued a standing warrant for his arrest. Denny mentioned this to the doctor who called the authorities. Denny knew that being in jail would help Brent get services, but would his son see this as a betrayal? “Brent was trusting me and went along with me willingly,” he says with a sigh. “I felt deceitful. That’s a shitty way to treat anybody.”

Shortly afterward, Denny quit his job. The strain of dealing with his son’s illness was simply too great. “I was feeling a tremendous increase in pressure to try to solve some problems for Brent,” he says. “I really hadn’t done anything for him in the past. I had always assumed it would be taken care of.” Denny didn’t mention anything about Brent to his co-workers. He told them he wanted more time to help out his mother.

Brent stayed in the Washington County Jail for almost two months. Denny would visit and bring him cigarettes and candy. “We had a lot of one-sided conversations,” Denny says. “How’s the food? Are you okay? What have you been doing? For the most part, Brent just sat there.”

On Dec. 3, Washington County District Judge John Lewis sentenced Brent to time served in jail and two years' probation. Brent walked out of the courthouse the same day. Denny was flabbergasted. He called Brent’s probation officer. “He needs help!” he said. “He can’t live out on the streets! Jesus Christ! He’s gonna fall through the cracks again. He’s got no place to go!”

Brent vanished into the streets and bridges of Portland. A few weeks later, after a couple of violent episodes, he was arrested and wound up in the Ryles Center, a short-term locked residential care facility in Southeast Portland. Denny came to visit him and felt a flicker of hope. Brent seemed to be making progress. “I felt we were making headway,” he says.

Denny made frequent visits, excited by his son’s new attitude and more talkative manner. On Jan. 20, he brought along some cigarettes and a bag of candy. As he got ready to leave, one of the nurses asked Brent to hand over the goodies for safekeeping. Brent refused. He went to the bathroom and ate up two rolls of Lifesavers. Then he came out… and flipped. He began to rant. “Don’t fuck with me!” he shouted. “Martin Luther King would destroy this place!”

The nurse tried to calm him down—in vain. Raging out of control, Brent threatened to put out a contract on the nurse, pointing his finger at the man’s face. The man called for backup.

Denny could not believe his eyes. As he turned to leave, he felt tears streaming down his face. He walked down the hall, trying not to listen to the sounds of the orderly subduing Brent, and his son’s muffled screams.

No one knows quite what to do with Brent Olson. The Ryles Center sent him to Emanuel Hospital, who sent him to Multnomah County Jail, who sent him to Washington County Jail for probation violation. The judge sentenced Brent to 90 days, but he was released after just two weeks because of overcrowding.

He showed up at his dad’s house a week later where he has stayed ever since.

For the past four months, Denny has been trying to get his son on the Oregon Health Plan, which in Washington County has just been extended to cover mental health. His application was turned down because he is already on Medicare, which is supposed to offer more comprehensive benefits. Ironically, this has actually made it harder for Brent to get into certain programs which prefer Oregon Health Plan clients because the plan pays more. Denny has also been trying to get his son into the Luke-Dorf, a group home in Tigard for people with mental illness. Perhaps, he thinks, one of the counselors there will persuade Brent to try clozaril, a new drug that has helped other schizophrenics. So far, Brent has refused because the drug requires weekly blood tests. This attitude makes Denny roll his eyes. “Why the hell wouldn’t you want to try that if it’ll give you a chance to function in society and get along?” he asks with a sigh of exasperation. “What kind of attitude is that?”

In the meantime, Brent spends his days veering between blank-faced passivity watching TV or listening to his punk records and sieg-heiling. On a recent visit, he was pessimistic about his future, even if he is admitted to the Luke-Dorf. “The truth is, the odds for me getting kicked out are high because I don’t like rules that don’t make any sense,“ he says nonchalantly. “I don’t obey rules unless I want to.”

He takes a sip of his white Russian and taps his cigarette with an oddly patrician air. “My future is pretty bleak,“ he smiles. “It looks like I’ll be on the street again at some point.”

Denny’s relatives shake their heads over his predicament. “He’s living in a squirrel cage,” says Denny’s mother-in-law, Dorothy Anne Vose. “He’s cooking for Brent. He’s doing things for Brent. It’s hard on him. He’s lost his whole life. It’s an impossible situation. Denny can’t keep go on doing this. I don’t know how he keeps it up.”

“Nobody can live with a person like that and expect to have a normal life,” says Brent’s sister, Sandy Olson. “He’s withdrawn from people. How long can anybody take that?”

Sandy thinks her brother belongs in a “controlled environment,” such as a mental hospital. And looking to the future, her feelings about her brother are ambivalent. “He’s my brother and everything,” she says, “but I really don’t look forward to the day when he’s my responsibility.”

Denny himself is stoic about their struggles. He spends his afternoons taking care of the grounds, driving around the lush green grass on the tractor mower, and from time to time he looks at his son and tries to reconstruct the face of the boy he loved so much.