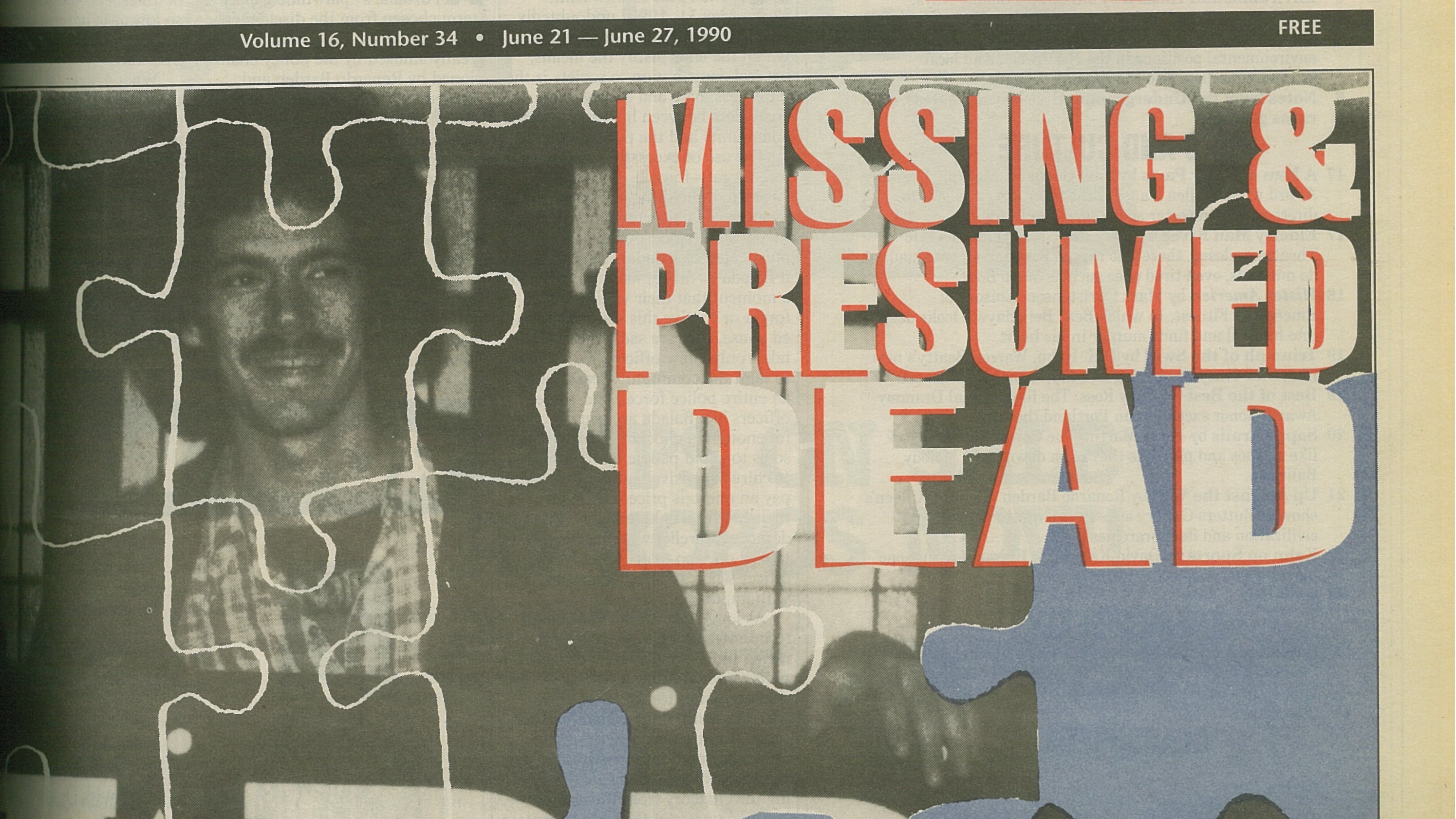

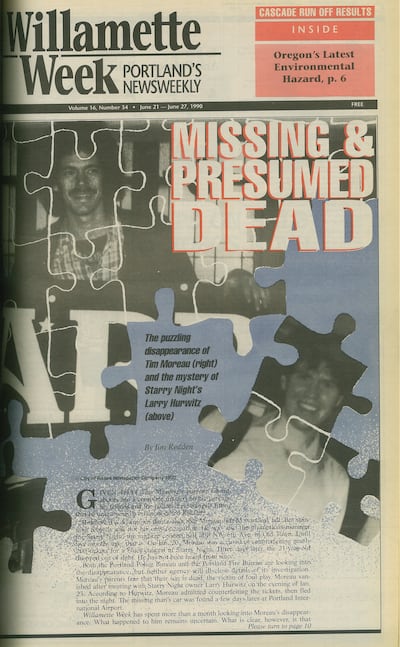

In June 1990, Willamette Week published the first in a long-running series of stories by Jim Redden spanning 30 years and four newspapers about the murder of Starry Night promotions manager Tim Moreau by the club’s owner, Larry Hurwitz. Moreau had disappeared the previous January, purportedly after confronting Hurwitz about ticket counterfeiting for a John Lee Hooker concert. When questioned by police, however, Hurwitz said it was Moreau who had confessed to the counterfeiting scheme and fled.

This story first appeared in the June 21, 1990, edition of WW.

Given that Tim Moreau’s current whereabouts are a complete mystery to his parents, his friends and the police, it is strangely fitting that he once owned a business called Riddlers.

Riddlers is a downtown dance club that Moreau helped start last fall, but spinning records was not his only occupation. He was also the promotions manager for Starry Night, the midsize concert hall at 8 NW 6th Ave. in Old Town. Until five months ago, that is. On Jan. 20. Moreau was accused of counterfeiting nearly 200 tickets for a blues concert at Starry Night. Three days later, the 21-year-old dropped out of sight. He has not been heard from since.

Both the Portland Police Bureau and the Portland Fire Bureau are looking into the disappearance, but neither agency will disclose details of its investigation. Moreau’s parents fear that their son is dead, the victim of foul play. Moreau vanished after meeting with Starry Night owner Larry Hurwitz on the evening of Jan. 23. According to Hurwitz, Moreau admitted counterfeiting the tickets, then fled into the night. The missing man’s car was found a few days later at Portland International Airport.

Willamette Week has spent more than a month looking into Moreau’s disappearance. What happened to him remains uncertain. What is clear, however, is that there is far more to this case than meets the eye. Among other information, WW has learned the following things:

- Moreau is not the first Starry Night employee to disappear under suspicious circumstances. One of the club’s former security guards fled in 1983 after allegedly stealing money and drugs from Hurwitz’s office. Hurwitz was detained and questioned by law enforcement officials at the time about allegations that he plotted to kidnap the missing employee’s parents and hold them for ransom.

- Although Hurwitz has denied any involvement in the counterfeiting scheme, the phony tickets that were seized on January 20 apparently were copied on the special paper stock that had belonged to Hurwitz. Hurwitz has told different stories to different people about why he had this stock, some of which was found in Moreau’s room by police. See accompanying story.

- Contrary to the impression left by published news reports, Hurwitz was not alone when he met with Moreau on Jan. 23, Hurwitz asked George Castagnola, a longtime friend and employee, to monitor the meeting from an adjoining room. During the course of a 1981 drug raid, Castagnola was arrested on attempted murder charges. Hurwitz said he asked Castagnola to be present Jan. 23 in the event that Moreau had to be restrained.

- Although Moreau has been characterized in the media as an average, clean-cut kid, he was apparently a troubled young man experimenting with drugs and sex, including sadomasochism. One former roommate reports that he may have been bringing prostitutes home on a regular basis for sex. Police reportedly found bondage equipment in his room after he vanished.

No one has yet been charged with any crime in this case. The police have not accused anyone—including Hurwitz—of being responsible for Moreau’s disappearance. But those familiar with the investigation say that it is anything but a simple missing persons case.

Moreau’s disappearance was well publicized. On Jan. 20 of this year, roughly 180 counterfeit tickets were seized at the door of a Starry Night show featuring blues legend John Lee Hooker. The phony tickets were seized by the show’s promoter, Monqui Productions, after it was learned that they were being sold through Day for Night, an Old Town nightclub with close ties to Hurwitz. Suspicion for the counterfeiting immediately fell on Moreau after Hurwitz claimed he had lent Moreau money to buy tickets for resale at Day for Night.

According to Hurwitz, he met with Moreau three days later at Starry Night. During the three-hour meeting, which ended at 10 pm, Moreau confessed to counterfeiting the tickets, Hurwitz says. He also says that Moreau admitted keeping the money he had been lent to buy real tickets and offered to lead him to where it was stashed. Hurwitz was to follow Morrow’s car in his own. Instead, Hurwitz claims, the missing man shook him at a red light and vanished.

Many people scoff at the notion that Moreau could have eluded Hurwitz. Moreau drove a battered 1981 Datsun sedan and Herro and Hurwitz owns a 1985 Pontiac Fiero. “Moreau’s car is a piece of shit that’ll barely do 55,” says one law enforcement official close to the case. “Hurwitz drives a sports car.”

Almost everyone who has attended a Starry Night show is familiar with Hurwitz. Not only does he run the hall, but he also routinely acts as the master of ceremonies, roaming the stage between sets and announcing upcoming gigs over the building’s massive public address system. In person, Hurwitz is tall and lean, with chiseled good looks and piercing eyes. His entire manner oozes self-confidence, and well it should. In many respects, Hurwitz, 35, is at the top of the heap of the local concert business.

Hurwitz’s hall, Starry Night, occupies an envious niche in the Portland music scene. Smaller than the Civic Auditorium but larger than such nightclubs as Key Largo and Satyricon, Starry Night is virtually the only local venue that can handle the array of moderately successful acts that make up the majority of the touring music industry. “He gets the bands on their way up and on their way down,” says one competitor.

Hurwitz is also involved in Day for Night, an upscale restaurant and lounge at 135 NW 5th Ave., just two blocks north of Starry Night. That nightclub, which features local bands and small-time touring acts seven days a week, is owned by Hurwitz’s girlfriend, Beatrice Wolbaum, and his former father-in-law, Harvey Freeman (who also goes by the name of Freier). Hurwitz personally lent Wolbaum and Freeman the money to start Day for Night. Wolbaum borrowed $15,000, and Freeman took a loan of $5,000. Although Hurwitz claims that he has no business interest in the nightclub, he books its music and frequently pays its bills with checks drawn on Starry Night’s account.

Hurwitz admits that rumors about his business finances have swirled within the local music community since he first opened Starry Night. “When I started, people said my money came from the mob on the East Coast,” says Hurwitz. “In the mid-1980s, people said I was getting my money from the bhagwan. Now people suspect Larry’s money came from cocaine. None of it is true. I’m so clean, it ain’t funny.”

Although Hurwitz says he’s clean, he has been the subject of a law enforcement investigation in the past. In May 1983, another of Hurwitz’s employees disappeared after an alleged theft. At the time, Hurwitz was detained and questioned about his involvement in a wild scheme to kidnap the employee’s parents and hold them for ransom.

In early 1983, Hurwitz employed an individual named John Stanley for a number of jobs at Starry Night, including security. As part of that job, Stanley lived in a small room at the concert hall. On May 20 of that year, after everyone else had gone home, Stanley allegedly broke into Hurwitz’s office. According to police records, he stole $3,100 from the office. According to former Starry Night employee Evan Parrish, however, Stanley also stole $3,000 worth of cocaine. Parrish was employed at Starry Night when Stanley disappeared, and he participated in the events that followed.

Parrish said Hurwitz was outraged at the theft and immediately swore to kill Stanley. “That’s what first came into Larry’s head, to kill him,” Parrish claims.

The next day, Hurwitz went to Portland International Airport to look for Stanley’s car. While driving around the airport parking lots, he was stopped by Leslie Martin, a police officer for the Port of Portland, which operates the airport. According to Port records, Martin originally thought Hurwitz might be a thief. Hurwitz explained about the Starry Night theft, however, and said he was checking to see if Stanley had caught a flight out of town. Hurwitz did not find any trace of Stanley at the time.

According to Parrish, however, someone called Hurwitz that evening at Starry Night to report that Stanley’s car had been spotted in Salem at a Denny’s restaurant. Parrish said Herwitz decided to drive to Salem and asked three other people to accompany him: Parrish himself; another employee whom Parrish recalls only as “Marco”; and Hurwitz’s brother, David, who was co-owner of Starry Night until 1985. Larry Hurwitz told the others they were going to track Stanley down and kill him, Parrish says. “Larry had a .32-caliber revolver and Marco had a knife,” Parrish recalls. “We went to Salem to kill Johnny. We were going to take him out in the woods and bag him. Looking back, I can’t believe that we really did that. I don’t know what I was thinking.”

The men did not find Stanley in Salem, but learned that he had apparently caught a Greyhound bus to Texas where his parents lived. Frustrated, the group returned to Starry Night where, Parish says, Hurwitz hatched an elaborate scheme to lure Stanley’s parents to Portland before their son arrived in Texas. According to Parrish, Hurwitz intended to hold the parents for ransom.

Parrish says the scheme involved having members of the group pretend to be Portland police officers and doctors from Emanuel Hospital using the phones. At Starry Night, the employees called the parents at Hurwitz’s direction, explaining that Stanley had been in an automobile accident and was in critical condition at the hospital. The employees encouraged the parents to come to Portland, claiming that their son was not expected to live. As Parrish recalls, he and Hurwitz planned to meet the parents at the airport pretending to be plainclothes police officers. The parents would then be taken to Hurwitz’s apartment or a motel, where they would be held until Stanley returned everything he had stolen.

Willamette Week has been unable to reach Stanley or his parents for confirmation. Much of Parrish’s story is corroborated, however, by the Rev. Lorin Moseley of Hillsboro, who has known the Stanley family for years. Mosley says that he was called by Stanley’s brother, Cash, after the parents had been contacted by two men claiming to be a police officer and a doctor. Cash Stanley asked Moseley to visit his brother and gave the minister two phone numbers that had been given the parents. Mosley says he called the numbers, one of which was answered by someone who identified himself as a police officer, the other by a person who said he was a doctor at Emanuel Hospital. Both of them claimed that Stanley had been in a car accident and was in critical condition. “They really had it fixed up good,” Moseley says of the phone scheme. “I thought it was all true.”

Mosley says he became suspicious, however, when the person posing as the doctor refused his request to visit Stanley in the hospital. As a minister, Mosley had never before been refused a request to visit anyone who was near death. Mosley called Cash Stanley back to express his confusion, only to learn that the parents had already boarded their plane for Portland. The clergyman then called the Portland police to explain what had happened. The police checked the phone numbers and, according to the Port of Portland records, determined that they belonged to Starry Night. The records identify the callers as “Parrish” and “Schneider,” both of whom are named as Starry Night security guards.

Port police were promptly notified of the situation. A number of them were subsequently assigned to meet Stanley’s parents. When the flight arrived, one of the officers was Martin, the same person who had stopped Hurwitz two days earlier in the airport parking lot. When she arrived at the gate, Martin recognized Hurwitz in the crowd waiting for the plane. The port officers approached Hurwitz, who was with Parrish.

As recorded in the police report, the officers detained the two men and escorted them to a small conference room. There, Hurwitz denied luring Stanley’s parents to Portland. He claimed to have learned that they were on the flight through an anonymous tip. “I thought it was all over for us,” Parish says. “Larry did too. He was shitting bricks.”

Stanley’s parents were notified of the situation after they arrived and they promptly booked another flight back to Texas. The airport guards then released Hurwitz and Parrish. The incident was documented in a report which was then forwarded to the Portland Police Bureau. It accused Hurwitz and Parish of harassment and impersonating police officers.

Although the report was forwarded to the Multnomah County district attorney’s office, nothing ever came of it. Helen Smith, the assistant District Attorney who received the report, says she sent it back to the police for more work. She never saw it again. No record of a follow-up investigation can be found in the files of the police bureau or the district attorney’s office.

Mosley says that he saw Stanley several years ago in Portland. He believes the former Starry Night employee is currently living in Texas, but he does not know where.

When asked about this incident by Willamette Week, Hurwitz confirms some of the details and denies others. He also tells a slightly different version of events than the one he gave Port police. Hurwitz insists that Stanley stole only cash, not drugs. He admits driving to Salem with his brother and some employees, but says that they were only trying to find—not kill—Stanley. And he admits calling Stanley’s parents in Texas, but says that he did not try to trick them into coming to Portland. Instead, Hurwitz says, he merely told them what their son had done and asked them to come out to find him. When told about the elaborate phone scheme described by Parrish and Mosley and confirmed in the Port report, Hurwitz says that it must have been hatched by some of his employees. Without his knowledge, Herwitz cannot explain why Stanley’s parents returned to Texas so quickly. “It’s so long ago. I can’t remember,” he says.

Hurwitz has always admitted meeting with Moreau at Starry Night just before his former employee disappeared. Published reports have implied that the two men met alone. This is not the case. The night Moreau disappeared. His meeting with Hurwitz was witnessed by George Castagnola, a Starry Night employee, whom Hurwitz also refers to as a friend. Hurwitz says he asked Castagnola to be present in the event that Moreau became violent and had to be restrained.

Castagnola is not a trained security guard, but he helps arrange the nuts and bolts of the shows at Starry Night. According to records on file with both the Portland and Gladstone police departments, Castagnola was arrested during a drug raid in Gladstone on April 14, 1981. During the raid, police entered a room and saw Castagnola with a gun in his hand. The officers retreated and heard a shot. By the time they reentered the room, Castagnola had dropped the gun and was lying on the floor. He was arrested and charged with attempted murder and three counts of possession of controlled substances, marijuana and hashish. Records in the Clackamas County Courthouse indicate the attempted murder charge was dropped.

After Castagnola swore he did not hear the police announce the raid, concluding instead that he was being robbed and needed to protect himself. The gun discharged accidentally into the ceiling. Castagnola said when he raised his hand to surrender, after recognizing the police. After a series of legal maneuvers, he pleaded guilty to one count of possession of a controlled substance on March 21, 1983.

Hurwitz insists that Castagnola did not harm or otherwise interfere with Moreau on the night he disappeared. “Foul play is not a part of his character,” Hurwitz says of his friend and employee.

After Moreau vanished, Hurwitz voluntarily took a lie detector test about his missing employee. Hurwitz claims the test cleared him of any involvement in the disappearance, but those following the case dismiss its significance for two reasons. First, the test was not administered by the police, but rather by a private polygraph examiner hired by Hurwitz. And second, Harvey Freeman Hurwitz’s, former father-in-law, claims to have been a polygraph consultant in the past. According to papers Freeman filed with the Oregon Liquor Control Commission when he was applying for a liquor license for Day for Night, he worked in that capacity from November 1985 to March 1988 for Chapman Investigations in Los Angeles and Merit Protective Service in Hawaii. Hurwitz admits that he asked Freeman about the test before taking it, but he insists that the co-owner of Day For Night did not “coach” him on it.

If Hurwitz is more complicated than he appears on the surface, so is Moreau. News reports—including those in Willamette Week—have so far painted a less than complete picture of the missing man. He has been portrayed primarily as a former Eagle Scout from a middle-class family in New Orleans with an interest in music. But there is another, darker side to Moreau’s personality that has not yet been reported. At the time of his disappearance, he seems to have been a deeply troubled young man with an unsettled personal life.

Jason Lally, one of Moreau’s former roommates, says the missing man was a “mama’s boy” when he arrived in Portland to attend Reed College in August 1986. Moreau had been overweight before he left home but had begun shaping up by eating a vegetarian diet and sticking to an exercise regimen. According to both Lally and Hurwitz, Moreau began taking LSD shortly after arriving at Reed. By the time he finished his first year of school, he was deeply disillusioned about the college and most of his students whom he put down as “hippies.” Many students turned on Moreau in response. “About the only good thing you can say about him is that he lost weight between his first and second year,” says one former classmate.

Moreau quit school in December 1988 to pursue a career in the music business. with friend Wade Benson, he started Riddlers, a recorded music dance club staged twice weekly at the Red Sea Restaurant, 318 SW 3rd Ave. In March 1989, Moreau was hired at Starry Night where he helped with promotions, among other things. Lally reports that his former roommate was “on top of the world” when he got the job from Hurwitz and became deeply committed to his employer’s success. “Larry took him under his wing,” Lally says. “Tim totally worshiped the guy.” L

Lally believes that Moreau continued to experiment with illegal drugs while working at Starry Night. Hurwitz confirms this saying that his former employee would occasionally show up late for work, displaying the signs of an all-night binge. Both Lally and Hurwitz say that Moreau also began experimenting sexually, including trying group sex, homosexuality, and sadomasochism. One member of the local music community says Moreau would sometimes show up at concerts “wearing eye makeup and and all messed up.” Lally says Moreau regularly brought home women who appeared to be prostitutes. He says many of these women obviously outclassed his former roommate. “Some of them were downright professional looking, if you know what I mean,” Lally says, adding that he believes police found leather restraints and other devices in Melrose’s room after he vanished.

The Portland police have assigned Moreau’s case to Steve Baumgarte, a detective in the homicide division. He will not speculate on the significance of any of these incidents. Instead, Baumgarte merely asks anyone with information to call him. Without a body—dead or alive—there’s not much anyone can do to solve the riddle of what happened to Moreau after he left his meeting with Hurwitz five months ago.

Editor’s note: Without a body, police didn’t have enough evidence to charge Hurwitz with murder, but Redden’s story led to an immediate collapse in business at Starry Night, and Hurwitz sold the club six months later. Redden left Willamette Week in 1991 to start his own newspaper, PDXS, and continue his crusade to bring Moreau’s murderer to justice. Hurwitz sued WW and Redden for libel, a case that was thrown out of court, but not before depositions revealed substantial evidence of tax evasion by Hurwitz. While Hurwitz was in prison for tax evasion, the Moreau murder case finally broke when another Starry Night employee confessed he had helped Hurwitz strangle Moreau with speaker wire and dump his body on the Washington side of the Columbia Gorge. Hurwitz pleaded no contest to murder in 2000, was sentenced to 12 years, and got out in eight. Moreau’s parents sued Hurwitz for wrongful death in 2001, and he settled for $3 million, a figure he still hadn’t fully paid before he was busted in California for cocaine trafficking in 2019. Hurwitz returned to prison in Oregon for violating the terms of his early release. Moreau’s body has never been found.