This story first appeared in the Dec. 17, 1997, edition of WW.

The city streets where gangsters run are full of stories.

Few are as frightening as the tale of the Richmonds, a group of men who may be more calculatingly brutal than any this city has ever seen.

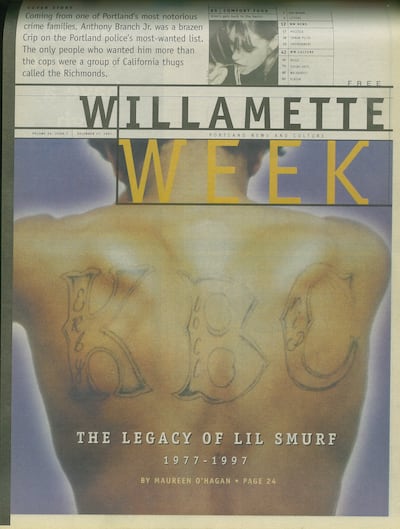

According to legend, the Richmonds came to town from California in early 1995 on a murderous mission. Their target was 18-year-old Anthony Branch Jr., one of Portland’s most notorious gang criminals.

“They came up here to seek revenge,” says Portland Police Detective Kerry Taylor, “and they carved a path through the people around him.”

In a shooting spree that began in February 1995, the Richmonds critically wounded two people and killed three more. All of them were relatives or associates of Anthony Branch Jr., or Lil Smurf, as he was known on the streets.

On Oct 9 of this year, Lil Smurf himself was gunned down in the parking lot of a Northeast Portland strip club. He had been out of prison for less than a month.

So far, only one Richmond has been prosecuted for his part in what the DA’s office is now convinced was a deliberate and calculated crime spree.

At this point, the rest have gotten away with murder.

Like many crime stories, Lil Smurf’s begins and ends with drugs.

In a life that was chaotic at best, the only constant was cocaine.

His dad, Anthony Branch Sr., and his mom, Monica West, never married, never lived together and never took responsibility for the son they brought into the world. Both spent their energy supporting their own habits.

West dropped out of Cleveland High School as a junior, and never seems to have had steady work. Instead, she spent her time committing crimes.

In June 1977, three months after Lil Smurf was born, she was arrested for prostitution on North Alberta Street and Haight Avenue, just blocks away from their home at 7046 NE 6th Ave. She also shoplifted, forged checks and committed forcible robberies, racking up 31 felony convictions in the past 20 years. She is currently incarcerated at the Oregon Women’s Correctional Center in Salem on a 1996 theft charge.

In a phone interview with WW, West insisted she was a good mother. “My drug addiction didn’t affect my son,” she said. “I know it didn’t.... I wasn’t absent that much. Maybe six months here or there. I played a big part in my son’s life.”

Lil Smurf’s dad, Anthony Branch Sr., known on the streets as Cheese, came from an extended family that for years has been plagued by drugs, criminality and joblessness.

Although some Branches may not be involved in crime, says Deputy DA Chuck French, who worked in the gang unit for five years, “the family has been notorious.”

In an arrest history that dates back to 1976, Cheese had seven felony convictions, including car theft and drug possession.

With such mentors, Lil Smurf was on shaky footing from the start. “Mom and Dad didn’t care enough about that child to give him some kind of guidance and instruction,” says Sherman Taylor, a counselor at the McCoy Academy, a community-based alternative school. “He never had a man in his life other than to give him some dope and say, ‘Here, kid. Go make some money.’”

In 1989, a stepfather came along. After having four children together, Lil Smurf’s mother and Chris West decided to marry. According to court documents, the union was made possible with the help of guards who agreed to take them from their jail cells to the ceremony. Police describe Chris West as an addict and a mid-level crack peddler with 12 felony convictions including drug dealing, theft and robbery. One Portland cop says that his drug business thrived with the help of both Lil Smurf and Cheese, who acted as his lieutenants.

Robert Richardson, a minister who counseled the younger Branch for nearly half of his life, says it never occurred to Lil Smurf to do anything but follow his parents' example.

“He got dealt some early cards,” Richardson said, “and I don’t think he could get them out of his hand.”

In 1988, when Lil Smurf was 11, Portland woke up to its first drive-by gang shooting, the murder of Ray Ray Winston in Columbia Villa, a public housing project in North Portland.

One year later, Lil Smurf became a gangster. He joined the Kerby Block Crips, in part because his older cousin, Jonathon D. Norman, was a Kerby, and Lil Smurf needed a sponsor to join the group. At the time, Lil Smurf lived with his aunt in the Humboldt neighborhood, a Kerby hood. According to police, Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard forms a crude east-west dividing line between Crips and Bloods territory, although there are pockets of each on both sides.

Like most local gang bangers, Lil Smurf never had the fancy cars, expensive clothes and diamond rings that MTV gangsters sport.

“Most of the real hardcore LA-style gang members do not do it for the money,” says deputy DA French. “They do things because of an image and the respect it gets them on the street. Most of the time, they only sell enough drugs until they have $200 or $300 in their pocket and then they stop. Most of them are interested in hanging around one another and acting like comrades in arms.”

By age 12, Lil Smurf was in his first gang-related fight. At 14, he was accused in a shooting. By age 16, he had been in front of the juvenile court at least 10 times. At that point, the system charged with helping Lil Smurf seems to have given up hope. “The court finds that Anthony Branch has received services from the finest juvenile court counselors in the county, from the finest treatment programs available in this community and has received services over an extended period of time,” Circuit Court Judge Elizabeth Welch wrote in July 1993 after Branch had violated the terms of his probation—again. “Mr. Branch’s anti-social behavior is accelerating and he is becoming an increasingly more dangerous person.” She sentenced him to the MacLaren School.

All told, the police stopped Anthony 44 times in his short life—a huge number, even more staggering than it sounds when you consider that he spent part of his teenage years in MacLaren, the Donald E. Long Home or the House of Umoja, and spent two years in prison on drug-dealing charges.

“He was public enemy number one in the gang world because of how active he was,” says Deputy DA Eric Bergstrom, who works in the gang unit. “At one point, I think the Gang Enforcement Team thought he was responsible for half the shootings out there—either he was doing them or he was the target of them."

So many attempts had been made on Anthony Branch’s life that he told police at age 18 that even he had lost track. On and off from the age of 15, Lil Smurf wore a bulletproof vest.

“He was recognized as somebody you did not want to stand next to—literally,” says Robbie Thompson, an investigator with the DA’s office. “Anyone who had a life-insurance policy on him would have had a safe bet,” says French.

Was it foolish bravado? A need for excitement? Or was it just plain lunacy that made Lil Smurf mess with the Richmonds?

No one will ever know. From rumors on the streets, police have pieced together this much: Sometime in late 1994 or early 1995, Lil Smurf made a drug run to Richmond, Calif. He got the drugs all right, but he never gave the dealers their money. Police say they’ve heard the ripoff was for as much as $50,000 worth of cocaine.

When Lil Smurf was arrested a few months later with 22 grams of cocaine, it lent credence to the story. (For that crime he was eventually sentenced to 29 months in prison.)

According to rumor, Lil Smurf had become a marked man, the target of a caliber of gangbanger previously unseen in Portland.

“The Richmonds seem to be the real deal,” says Detective Derek Anderson. “People are genuinely afraid of them.”

Some say the reputation is deserved. The group members have loyalty to neither Bloods nor Crips, but are violent drug dealers who peddle their wares to both sides.

Their California roots gave them special cachet in Portland. “You automatically get respect if you’re from California,” explained Detective Neil Crannell. “That was part of it. But they earned it because they’re reported to have shot so many people.”

Police say there were probably only a half-dozen or so California transplants operating in Portland in 1995, but they beefed up their numbers by hooking up with some local hoodlums. Although their numbers were small, by 1996, the Portland Police Bureau was pressing to file racketeering charges against the group—something the DA’s office had done to a gang only once before, in a case against the Woodlawn Park Bloods, who had been around for a decade.

Lil Smurf cemented the Richmonds' reputation by drawing their ire.

“You hear a lot of talk about people putting out hits,” says deputy DA Bergstrom, “but I really don’t think they happen very often. With this case, though, I thought there was some legitimacy to the stories.”

According to a police report, at 3 am on Feb. 19, 1995, Lil Smurf, his cousin Norman, and a friend, Harry Villa, were driving around Northeast Portland and stopped at some apartments on Northeast 6th Avenue and Jarrett Street. Within minutes, several men confronted them on foot, and at least one opened fire, cranking off 17 or more rounds at Branch’s car. Villa, 20, was hit in the back before the car sped away, with Norman steering from the back seat and the two others crouched in front.

The suspects, Dante Raines and Terrell Pittman, were associated with the Richmonds. Villa, who fully recovered from his injuries, declined to press charges in the shooting, and the case was dropped.

Two months later, according to police, Lil Smurf’s stepfather, Chris West, 36, was filling up his tank at the ARCO on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and Ainsworth Street when a man in a black sweatshirt came running toward his car. The suspect stood behind West’s car, at one point firing from just a few yards away. West was hit four times in the back and spent the next month and a half in a coma. He was partially—but temporarily—paralyzed.

West told police he never saw the gunman but knows exactly who did it: Keith Bowman, who was associated with the Richmonds. West also claims that a few weeks before the shooting, Bowman pointed a gun at his head and robbed him.

“Chris West stated that he believes that the Richmonds are going to kill the members of Anthony Branch’s family until they can kill him,” detective Brian Grose wrote in a police report on the shooting.

“I have also heard several rumors regarding the fact that the Richmonds may come back and try to kill Chris West because they are not satisfied with him being partially paralyzed,” Grose added. “I have also heard rumors about The Richmonds possibly attempting to kill other members of the Branch family or people associated with them.”

No one was ever prosecuted in the West shooting case.

On June 22, 1995, Toya Martin, a friend of Lil Smurf’s and the girlfriend of his cousin, Norman, had a party at her house on Northeast Ivy Street to celebrate her 21st birthday.

The next morning, police found the house riddled with bullets. Martin was killed in her sleep, with 10 gunshot wounds to her chest and shoulder.

There were no witnesses, but the case gave police their first big break. A few days after the shooting, police arrested Ronald Gunn, a Richmond associate, on a carjacking charge. On the day of trial, in October 1995, Gunn made a startling confession—he was one of four men who helped kill Toya Martin.

According to Gunn’s confession, he was with fellow Richmonds Leonard Drisker, Terrell Pittman and Keith Bowman on the afternoon of June 22, when the three began talking about hunting down Lil Smurf. Heavily armed, they drove to Martin’s house at 4 in the morning, because Pittman thought Lil Smurf would be there. When they arrived, they saw his car out front. They didn’t bother to find out if he was really inside.

“Gunn told us Pittman said for everyone to go to the windows of the house and shoot into the house,” a police report says. “When Drisker dropped his hand, the windows were broken by gunfire.” They fired from such close range that Pittman reached his hand through Martin’s bedroom window after it was broken and continued to unload his weapon. The killing was all the more brutal because Martin was once Pittman’s girlfriend.

The next day, Gunn and Pittman ran into Martin’s brother, Charles Jenkins, and smoked some marijuana with him. According to Gunn, Pittman talked to Jenkins “like nothing ever happened.” Pittman even told Jenkins he would find out who killed his sister.

Gunn pleaded guilty to manslaughter and is serving 10 years in prison. Because the confession of an accomplice isn’t enough to prosecute, the three other men have not been charged.

“It’s frustrating, because we believe we know who the three killers are,” says Deputy DA Bill Williams. “Until somebody comes forward who has information, and I’m certain there are people who do, we’re not going to be able to prosecute.”

On June 27, 1995, around 10 pm, police received a call about shots being fired at a black Monte Carlo traveling near the corner of Northeast 12th Avenue and Failing Street. A short time later, 17-year-old Patrick Curry, a friend of Lil Smurf’s, was pronounced dead with a single gunshot wound to the head. Deputy DA Marilyn Curry (no relation) says the young gang associate may have been an unintended victim of a war he wasn’t involved in. When he was killed. Curry was in Harry Villa’s car. Villa was one of just a tiny handful of Kerbys who stood by Lil Smurf when he was being hunted by the Richmonds.

Although many law enforcement sources are convinced that Curry was murdered at the hands of the Richmonds, the DA on the case is skeptical. “I wouldn’t bet a dime on it and I wouldn’t bet a dime against it,” prosecutor Curry says.

Because witnesses haven’t cooperated, no one has been prosecuted for the murder of Patrick Curry.

On Sept. 17, 1995, Lil Smurf wanted to celebrate.

It was the night before he was to plead guilty to drug dealing and begin a 29-month prison term, and he hosted a party for friends at Columbia Park.

At the time, he was occasionally sleeping at his father’s house, at 2025 SE Ash St. That night, however, he didn’t come home until 7 am.

Doing so saved his life.

At 1 am, two masked men heaved a boulder through the sliding-glass door to Cheese’s apartment. The men stepped through the shards and started beating him, while his female companion cowered in the cramped one-bedroom. According to police, who interviewed the woman, the men told Cheese they were after Lil Smurf. When Cheese wouldn’t—or couldn’t—reveal his son’s location, they shot him, repeatedly, in the legs and crotch.

“I think that’s done for a purpose,” says Detective Kerry Taylor, who investigated the case. “To get him to talk.”

Within minutes of the break-in, Cheese was dead. The woman was wounded in the abdomen but survived.

When the homicide detectives arrived, they found Branch clutching a photo of his son, as if the killers had made him hold this pointed memento before they put a final bullet in his head.

After Cheese was killed, according to police, the Richmonds' gunfire stopped. Not coincidentally, this was the same time that Lil Smurf began his 29-month prison sentence.

“It was everyone’s feeling that getting this sentence extended his life,” says deputy DA Bergstrom.

If prison officials hadn’t cooperated, Lil Smurf may not have survived, even inside the walls. Because the Richmonds' threats were so serious—and because prison officials feared the Richmonds were cunning enough to get to Lil Smurf even while he was behind bars—the Department of Corrections moved him to a California facility to serve his time.

Lil Smurf was released from prison on Aug. 22 of this year and immediately booked into Multnomah County jail to face new charges of racketeering. He was bailed out Sept. 13.

Lil Smurf had exactly 26 days of freedom before his past caught up with him. On Oct. 9, in front of a number of witnesses, he got in an argument about drugs with a man at the Viewpoint, a Northeast Portland strip club. The man pulled a gun and shot him at point-blank range. Lil Smurf was dead at age 20.

“I figured this was going to happen if he was out on the street,” deputy DA French says.

“Unfortunately, he got himself released on bail. Had he stayed in custody, he might have survived. He would have probably been over 30 when he got out. People probably wouldn’t be gunning for him by then.”

Ironically, police don’t think it was one of the Richmonds who killed Lil Smurf, but they refuse to release further details. They hope to make an arrest soon.

How to make sense of the story of Lil Smurf?

Although the wrath of the Richmonds makes the details dramatic, in some ways, it’s a classic tale. All the elements are there: the dysfunctional upbringing, the drugs, and a life so bleak that violent gangs seem like family, and crime becomes a form of employment. You could say that Anthony Branch Jr. is the product of society’s failings—the classic liberal argument.

But in other ways, the story goes beyond that simplistic analysis. “You read about the kid who never had a chance,” says French. “But that’s not the reality. It’s a knock on the community to say you’re going to grow up like Anthony Branch. Fact is, there are only a few Anthony Branches out there. There are probably only 100 or 200 hardcore gang members in this city who are willing to go out and do violent acts every night. He is a severe case. He exceeded even the norms of the Branch family.”

In this sense, he’s an example of a liberal’s worst nightmare. The juvenile-justice system gave Lil Smurf every resource it could muster, and it still failed to keep him out of trouble. Is it possible that some people simply can’t be saved?

“It wasn’t a surprise when he was killed,” says deputy DA Curry. “It was a mild surprise that he survived as long as he did.”

Perhaps the frightening part is that Lil Smurf’s legacy will live on long past his death. If you believe the stories, by stiffing the Richmonds in California, he brought to Portland a band of ruthless gangsters who got away with three murders and two major shootings.

It’s not a thought that law enforcement likes to dwell on.

“Quite frankly,” says DA investigator Thompson, “I don’t want them thinking they’re invincible.”

—Patty Wentz contributed to this story.