Three months after being hired straight out of Columbia Journalism School, staff writer Nigel Jaquiss filed this profile of Grant High School sophomore Brandon Brooks, a promising basketball phenom whose misbehavior and academic struggles off court too often eclipsed his breakaway performances on. Frequently suspended for fighting, Brooks once scored 60 points in a game to Lincoln rival Salim Stoudamire’s 38 in the days before Damon’s cousin would go on to play for the NBA’s Atlanta Hawks. One problem Jaquiss uncovered: Oregon state athletics’ academic standards were so low athletes could earn five D’s and two F’s, a GPA of 0.71, and still play.

This story first appeared in the March 4, 1998, edition of WW.

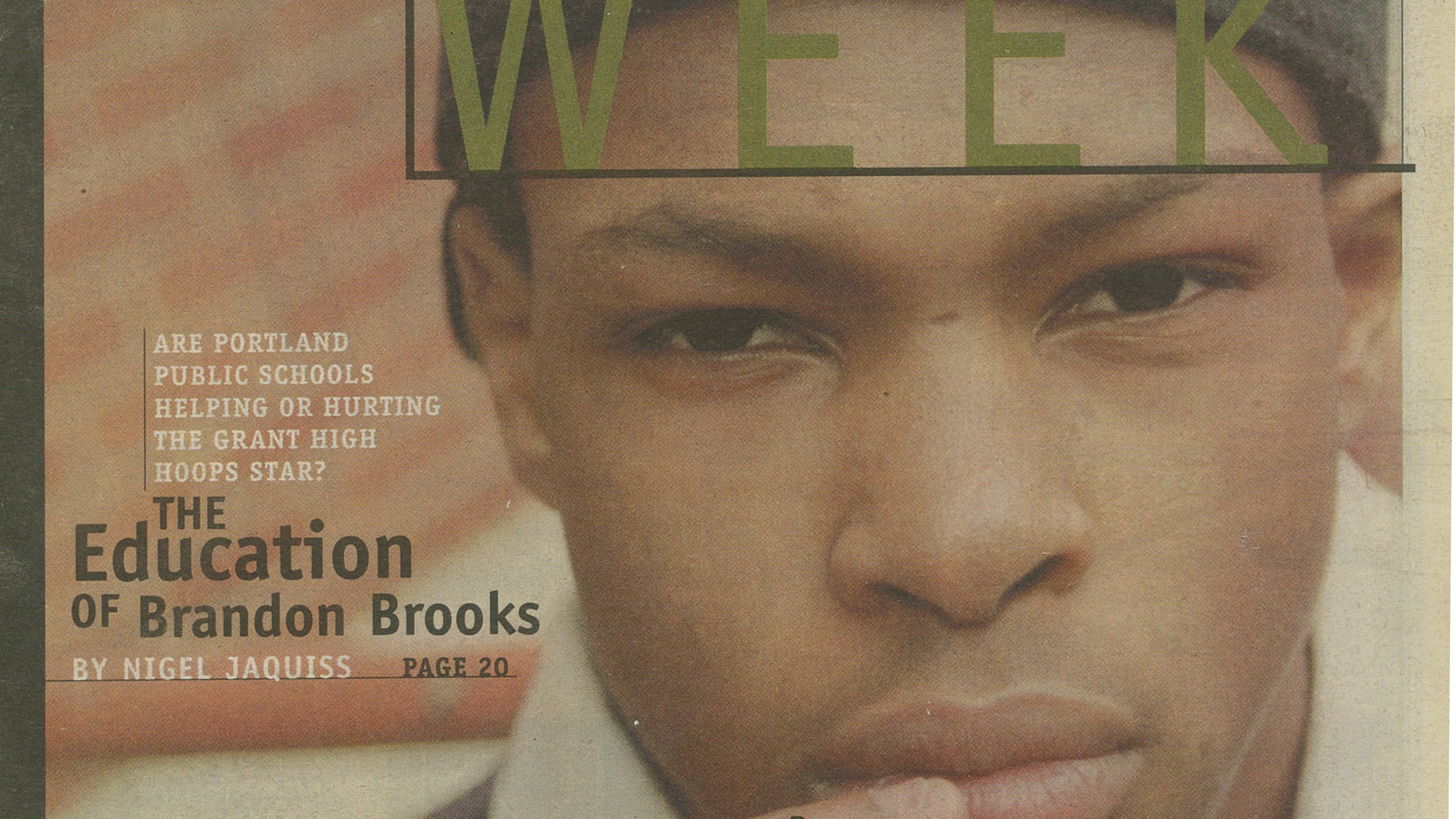

Brandon Brooks looks like an average kid. The gap-toothed 16-year-old Grant High sophomore favors jeans baggy enough to house a small family, an overstuffed Nike jacket and an assortment of hats that he pulls low over his narrow eyes. But Brooks is anything but average. He is both hugely talented and endlessly complicated—some would say troubled.

Last fall, Street and Smith, the basketball fanatic’s bible, said Brooks was one of the top 30 sophomore basketball players in the nation. Howard Avery, who coaches Oregon’s best players each summer in his Triple Threat Basketball program, believes Brooks is even better than that. “Brandon Brooks could play in the PAC-10 right now,” Avery says. “He could start for the University of Oregon and be better than any guard they’ve got.”

High praise for a kid who has played only two seasons of high-school ball, but Brooks is for real. In his last two games, he scored 118 points—a 60-point night, followed by 58 last Thursday against Franklin. He isn’t big—a shade under 6 feet—but Brooks possesses devastating speed, grace and intensity. He’s a fundamentally sound player who scores at will, threads bullet-like passes through swarming defenses and goes after the ball with the single-mindedness of a bill collector. “This kid is a pro—if we can get his academics in order,” Avery says.

That’s the complicated part. Brooks has drifted through six schools in five years, leaving something less than sweetness and light in his wake. His talent is rivaled only by his lack of discipline. “Whoever’s in his life has to take him on like he’s theirs,” Avery says, “otherwise he’ll find a way to fuck it up.” Although Brooks scored 118 points in two games last month, he was suspended from three others, once for fighting and twice for skipping school. “He’s 16 but he acts like he’s 8 or 9,” says one Grant administrator.

Brooks is walking a tightrope under which there is no net. He dreams of the NBA every night—but has trouble getting to class the next day. He’s spoken of as both the premier talent at Grant’s storied athletic program, and a symbol of everything wrong with high-school athletics. Some of those who follow local hoops say he could be the next NBA player from Portland; others worry that he’ll end up on the scrap heap, another high-school legend who never made it out.

It may be an unfair burden to place on a 16-year-old, but to many parents, coaches and administrators, Brooks represents a common dilemma: How do you help a kid who won’t help himself? Do you hold his hand or make him toe the line? Do you measure him by middle-class standards, or cut him some slack? Are those who are supposed to be educating and guiding him helping Brooks succeed—or setting him up to fail?

Located in Northeast Portland’s Grant Park neighborhood, Grant High has a proud tradition. A number of the school’s graduates have gone on to fame (or infamy), including former Sen. Bob Packwood and the current head of the Christian Coalition, Don Hodel. But perhaps Grant’s most revered alums are athletes. Women’s hoops star Cindy Brown set the NCAA single-game scoring mark in 1987 (60 points), won a 1988 Olympic gold medal and starred in the ABL. More recently, the Milwaukee Bucks' Terrell Brandon, who led Grant to the state championship in 1988, was named by Sports Illustrated the best point guard in pro basketball. Walk Grant’s aged linoleum hallways, and the key role of athletics in the school’s history is obvious. Trophy cases bulge with shiny metal, and pictures of teams stretching all the way back to the school’s founding in 1924 line the walls.

In recent years, the basketball program has struggled, but there was reason for fresh optimism last fall when Brooks unexpectedly registered at Grant. He transferred from Jefferson, bringing with him Jamal Kingham, one of Portland’s top big men. Even though he’d only played one semester at Jefferson, Brooks was well known to local hoop fans. He had starred in Avery’s program, and prior to his freshman year had been named by USA Today as one of the top 10 high-school players in Oregon.

Statistically, Brooks has exceeded expectations, averaging more than 30 points per game. Speed and quickness are his most potent weapons. He dribbles faster than opponents run, leaving defenders to either foul him or watch him blow by. His outside shot, formerly a weakness, has become dangerous. A point guard, he has great court awareness—the only problem is his passes often catch teammates unaware. Avery says he’s better than Terrell Brandon and Blazers guard Damon Stoudamire were at the same age.

In fact, one of the few players in Portland who offers Brooks serious competition is Damon’s cousin Salim Stoudamire, a freshman at Lincoln. The two faced off recently. Stoudamire—an inch or two taller than Brooks—opened the game with a breakaway dunk, as if throwing down a challenge. The contest quickly turned into full-court one-on-one. The other eight guys on the floor might as well have been playing bridge. Back and forth went the two prodigies trading three-pointers, no-look passes and coast-to-coast dashes. By half-time, Brooks had 24 points. He climbed into the bleachers and sat next to Avery. “I’m going for 50,” he told Avery. Brooks finished with 60, Stoudamire, 38.

Although Stoudamire is bigger, Brooks is faster and tougher. Love him or hate him, he’s always the hardest-working guy on the floor. He plays with a barely controlled fury, his face twisted in concentration. “I’m an emotional player because I want it more than anybody,” Brooks says. He’s rarely quiet, yapping at opponents, advising referees, exhorting his teammates and debating strategy with his coach.

Sometimes his intensity gets him in trouble. Early this season, Grant lost a close game to Benson. The next day, Benson coach Don Emry reviewed a videotape of the game and was so incensed by Brooks' behavior that he called the league office to complain. In a subsequent game against Franklin, Brooks' taunting led Franklin parents also to complain about him to the league office.

Immature behavior off the court has hurt Brooks as well. In his first week at Grant, he got into a fight and had an ugly altercation with school security staff. Toward the end of the season, he missed a crucial game after being suspended for another fight. On a Saturday, Brooks was playing three-on-three with some other gym rats at Lincoln. The game got rough and Brooks exchanged words with a competitor. They stepped outside and duked it out. Somebody called the cops, and Brooks made himself scarce. Later that week, the police visited him at Grant and charged him with disorderly conduct and trespassing on Lincoln property.

“Anybody besides me got into a fight, nobody would have heard about it,” Brooks says. Maybe he’s right. Pickup basketball is a full-contact sport, and fights happen. Still, Brooks was pushing his luck.

In fact, Brooks' behavior is a part of the reason he’s at Grant. After a brilliant start at Jefferson last season, he clashed with coach Bobby Harris—perhaps the Portland Interscholastic League’s strictest disciplinarian—and was kicked off the team. “Talent-wise he’s among the best in the city, but he had a poor attitude,” Harris says. From Jefferson, Brooks initially transferred to Lincoln, but soon left that school’s summer program because of disagreements with coach Mitch Whitehurst.

Avery, who has been Brooks' mentor since the player was in sixth grade, says, “Brandon Brooks is high-maintenance. Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.”

For many of those hours, supervisory duties fall to his grandmother, Mae Brooks. (Brooks lives with her; his mother, Michelle King, lives nearby.) Brooks' grandmother tries hard, but she’s overmatched. Although she says “Brandon has never been hungry, never been cold,” she worries about the bad influences that lurk near her Northeast 11th Street home. Friends show him fancy jewelry and rolls of cash, earned from dealing drugs. “You see them with that quick, easy money and you want some of that,” he acknowledges.

The sound of gunfire is a regular event in the neighborhood. One of Brooks' buddies, Fred Lincoln, was convicted of murder last summer. In Brooks' family, there are essentially no male role models—no positive ones, anyway. A number of his friends and cousins are gang members. His father is in prison and has never seen him play ball. Many people—Brooks included—fear that if he doesn’t stay in school, gang life awaits. “If I couldn’t shoot the ball, I might be out there with my cousins,” he says. “Basketball is the only thing keeping me going.”

Basketball, and a nearly full-time support staff at Grant. During the school day, Brooks is monitored by a team that includes vice principal Joe Simpson, athletic director Pam Joyner, and counselor Dan Anderson. If Brooks cuts class, he can’t play.

Two unexcused absences Brooks racked up late in the season may well have cost Grant a spot in the state playoffs. With three games left, Grant was tied with Wilson for the PIL’s final playoff berth. Fittingly, the teams were scheduled to play each other. Two days before the game, Brooks bagged a class and was told he couldn’t play against Wilson. Without him, Grant lost by seven. He missed the next game, against Madison, for another absence. Grant lost again. Brooks has no real explanation for his self-destructive behavior. “What I do, it’s what I’ve always done,” he says.

While Grant’s administration has been willing to punish Brooks for violations of school policy, a number of parents and other observers say that Grant coach John Stilwell cuts Brooks far too much slack in the gym. In fact, a blow-up over team rules—or lack of them—led assistant coach Steve Johnson to resign at mid-season. Johnson, who played 10 years in the NBA, including three for the Trail Blazers, insisted that Brooks be benched after missing three consecutive practices. “Playing time is the only leverage you have,” says Johnson, whose son Marques plays for Grant. “If you take away playing time, it’s the only way to determine whether basketball can help a kid.” According to Johnson, Brooks was held out of the next game, but agitated incessantly to be put in. Johnson finally lost his temper, and asked Stilwell to send Brooks to the dressing room. Instead, Stilwell put him in the game. Johnson quit soon afterwards. “I like Brandon Brooks,” he says. “I like his competitiveness. I don’t necessarily think he the problem.”

The problem, Johnson and other parents say, is Stilwell. A short, fidgety man in his 17th year at Grant, Stilwell is an enigma, a basketball coach who never played the game. He prefers golf, and peppers his conversation with the names of country clubs at which he plays. Stilwell coached Grant to state championships in 1986 and 1988, but he’s had only one winning season in the last four. Critics—both in the Grant community and in the PIL—accuse him of letting Brooks run the program—and run wild. Says the father of one Grant player, “My son calls him [Brooks] the coach.”

Stilwell’s motivations are unclear. He doesn’t seem to need the money—his wife’s a senior Nike executive—and he doesn’t need the aggravation of coaching, one of the most thankless jobs this side of working for the IRS. He says he coaches because he loves working with players. “I try to do what’s best for the kids,” he says. “If that’s not good enough, call me at Broken Top [a resort near Bend]. I’ll be on the first tee.” His supporters say he contributes generously to school fundraising programs and that his devotion is real.

In any case, parents judge the coach by what they see and what they hear. Anecdotes abound: Brooks told Stilwell off after the first Madison game; he grabbed the coach’s chalkboard and diagrammed his own play during a key moment against Wilson; he regularly refused to come out of games. “Stilwell has no control of his kids, no control whatsoever,” says Stanley Cage, a Grant player’s father. Others are critical as well. Benson coach Emry speculated that Brooks might be left off the all-PIL team as a gesture—even though he indisputably belongs on it. “Coaches around the league feel they have to censor him,” Emry says, “because his own coach won’t.”

Brooks won’t change, Steve Johnson believes, “until he’s put in a position where’s he’s held accountable by someone he respects.”

Stilwell contends that rigid rules aren’t the answer. “I don’t treat everybody the same because everybody is not the same,” he says. He believes doing whatever it takes to keep Brooks in his program is the best thing for the player.

Many observers disagree. Marshall Haskins, vice president of Self Enhancement Inc., a North Portland organization that works with at-risk youth, argues that Brooks badly needs structure and accountability but has been coddled. He also worries that giving Brooks special treatment sets a terrible example for others. “How many kids do you lose because you want to save Brandon Brooks? There are a hundred freshmen in the gym who think he’s God.”

For every critic who thinks Stilwell is doing Brooks a disservice by coddling him, there are many more who think that Brooks and all Oregon prep athletes are being coddled even more by the state’s pathetically low academic standards.

In much of the country, playing high-school sports is a privilege, one attained by earning a respectable grade point average. Many states—including athletic hotbeds such as California and Florida, and even academic backwaters such as Alabama—require that athletes carry a 2.0 GPA. In Oregon, all you need is a .71. That’s point seven one, as in less than a “D” average. Players need pass only five classes—any five. Most schools offer seven, which means athletes can flunk two and still play. They also don’t have to take any of the 15 core courses required for graduation. “The OSAA standard is wrong,” says Dan Anderson, Brooks' counselor at Grant. “It does an injustice to kids. It’s totally wrong. It tells them 70 percent is OK. If I work at 70 percent of capacity, I’m fired.”

Brooks' grades are private, but it’s safe to assume his cumulative average skirts close to the guideline—he was ineligible after the first semester last year, and basically stopped going to school in the spring. The tragedy of low standards is that they create no motivation for someone like Brooks, who has the aptitude to do well in school, but not the discipline.

At Vernon Elementary, Brooks was part of the Talented and Gifted program. His grandmother says he got off to a great start, but in middle school, right around the time people figured out Brooks was a hoop prodigy, his academic performance cratered.

“I’m a lazy person when it comes to schoolwork,” he admits. His favorite class is algebra, he says, because it’s the one in which his teacher really demands that he work.

But if you ask nothing, you’ll get nothing. “Kids will do whatever you let them,” says Haskins. When asked why the Oregon School Activities Association, which sets statewide standards, considers the dismal .71 acceptable, OSAA Executive Director Wes Ediger gives what could hardly be called a sufficient response: “I really can’t give you an answer.” And reform is not right around the corner. A recent proposal that students be required to pass all their courses didn’t fly, Ediger says.

The results of such a spineless policy are damning. The National Collegiate Athletic Association requires entering freshmen to have earned a 2.5 GPA, 13 core classes and an 820 on the SAT. “Brooks has the potential to be the best guard in Portland’s history,” says Haskins, but “at the rate he’s going now, he’ll barely get into junior college and that’s because they take everybody.” Many of the biggest names in local high-school basketball in recent years—Earl Clark, Dennis Nathan, Mike Marion and Denmark Reid to name a few—failed to meet NCAA requirements upon completing high school. “The five-pass rule is too low,” says Grant athletic director Joyner. “We’re not helping kids graduate.”

Another policy Joyner and many around the PIL think is hurting athletes is open enrollment. In place for decades, open enrollment was designed to allow academic choice and to further desegregation.

Nobody quibbles with those goals, but a third and unintended result of the policy has been free agency for disgruntled players. Brooks' transfer from Jefferson has been a hot topic all season. “In effect, kids can go wherever they want for athletic reasons,” says Joyner. Longtime Jefferson Coach Bobby Harris has grown frustrated with what he sees as excessive mobility. “It’s impossible to discipline a kid because every time you do, he just walks across the street to a new school.”

Brooks say he’s done moving; he hopes to play for Grant again next fall. The first measure of whether he’ll make it comes this spring. “If he continues to go to class, we’ll know we’re on the right track,” Joyner says. How much of this season’s turmoil was his fault depends on whom you ask.

Howard Avery and people who have known Brooks for a long time say Brooks is a leader. They also say he needs to be led—firmly. Ask Grant parents, and many will say Brooks is a punk. But most of them don’t know him, have never spoken to him. He’s no angel, nor is he quite the menace that critics fear; he’s just a 16-year-old kid with a lethal cross-over dribble and a lot of growing up to do. Brooks is supposed to get more out of school than headlines and applause; he’s supposed to be guided and educated. Currently, it’s too easy for him to glide through a system that demands little and may give back even less. And that’s a lesson that’s not lost on him. “If nobody’s hard on me,” Brooks says, “I’ll just do whatever.”

Editor’s note: After Jaquiss’ story, the Portland School Board raised the GPA required of athletes in the Portland Interscholastic League to a C average of 2.0. Brooks transferred to Jefferson High his junior year, where he struggled with the new eligibility standard. His senior year, however, he led the Democrats to their first state basketball championship since 1972. Signed to Arizona State, Brooks failed to meet academic requirements and played for two community colleges before winding up at USC, where his basketball career ended after he broke a leg in practice.