"It's the kind of movie that wouldn't get made today" is an elegy we're fond of giving for many late-20th-century films: blandly conventional dramas, campy action movies, original sci-fi, anything not based on pre-existing intellectual property. Breaking In (1989) represents a different category of cinematic dinosaur. It's a modest, low-concept indie before the Sundance boom that paired a Hollywood icon and a Gen-X newcomer, letting star power do what it could with the chips allowed to fall where they may.

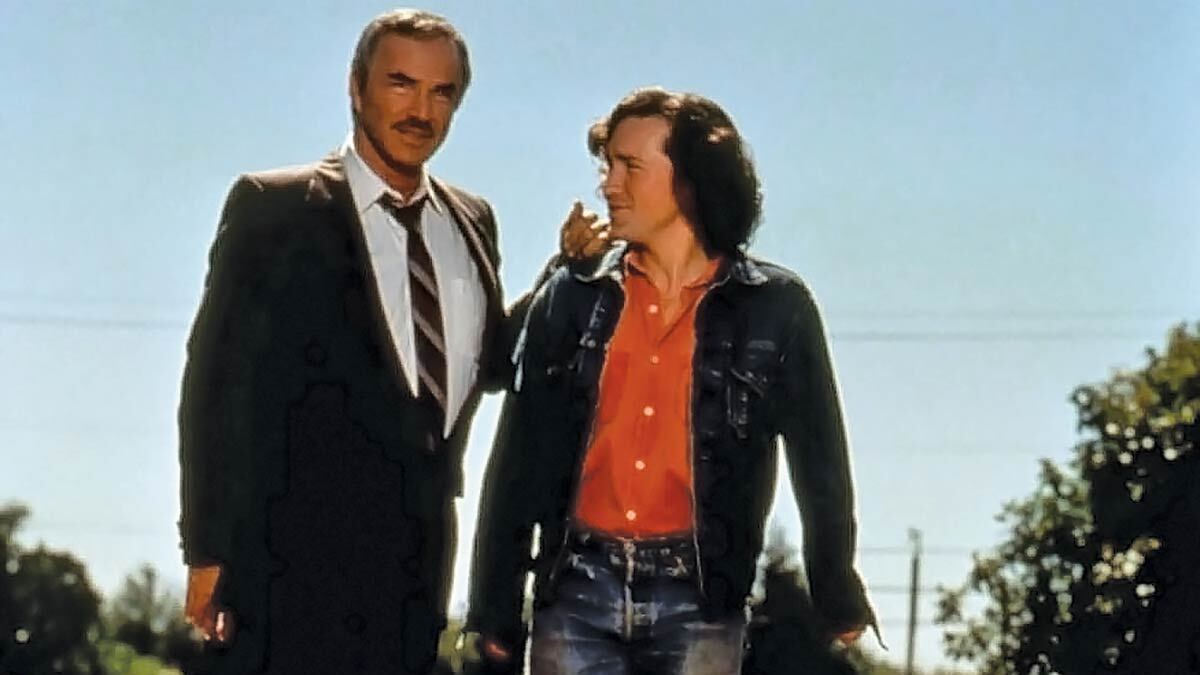

Filmed in Portland in the summer of 1988, Breaking In mostly adopts the breezy, self-assured personality of its star, the late Burt Reynolds. The Bill Forsyth-directed crime comedy casts Reynolds as Ernie, an expert safecracker with ample gray in that famous 'stache. Ernie takes on an apprentice in aimless burglar Mike (Casey Siemaszko), whom Reynolds instructs in the ways of larceny and calls "kid" approximately 500 times.

While Breaking In failed to crack $2 million for the Samuel Goldwyn Company or to reignite Reynolds' career (hold on for Boogie Nights, Burt), it's long on simple charms and street-level views of Old Portland, both of which will be on display when the film screens Nov. 19 at Hollywood Theatre as part of its #OregonMade series.

Portlanders Sara Burton and John Ceniceros recall the Breaking In set as cordial and exhilarating when they set to work on their first film as a personal assistant/set runner and art department assistant, respectively. The two future Hollywood pros were fresh from college and hustled around building safes, finding housing for actors and, perhaps most notably, picking up Burt Reynolds' toupees from the airport.

"They'd flown them in from Italy; I remember walking through the airport with them thinking no one would believe me," says Burton, who went on to work in Hollywood as a locations manager for the next decade before returning to Portland to start her own business, GirlScout Locations. Ceniceros would also work in the big leagues for the next decade, serving in the art departments of '90s worldbeaters like Forrest Gump and Armageddon.

Both describe Reynolds, then in his early 50s, as a class act and quite generous with his time. Still, hosting arguably the most bankable Hollywood sex symbol of the prior decade did lead to a couple of catcalls and at least one bizarre encounter. During filming, Reynolds' constant traveling companion and fellow Smokey and the Bandit actor Lamar Jackson came to the set with a wild story.

"[Lamar] was dying laughing," Burton says. "Some lady had shown up at the compound in an evening gown, and she brings out a thoroughbred horse and wants Burt to buy her horse. The horse was rearing all over the place."

While set in Portland, Breaking In makes use of the city in an observed but casual way. It could be anywhere, really: a little heist at the Oaks Amusement Park roller rink here, another score at the Alano Club of Portland there. A jail scene was filmed at Jefferson High School. Most everything about the John Sayles-penned script is roving and cheerful, and the movie's last act is based on character development more than any wildly improbable crime.

Burton and Ceniceros both recollect a man named Charles "Charlie" McCabe acting as a technical adviser on Breaking In. He'd supposedly been in jail for safecracking and was hired to inform some of Reynolds' snappy speeches about his illicit trade. But special effects coordinator Larry L. Fuentes sometimes looked at McCabe a little sideways, Ceniceros says, especially when the ex-con shared details on the exorbitant amount of dynamite he'd use to blow a box.

"It turns out, he had not been a safecracker," Ceniceros says. "He'd actually gotten busted for fraud, and here he was defrauding the production. I guess that's what you get when you hire criminals."

SEE IT: Breaking In plays at Hollywood Theatre, 4122 NE Sandy Blvd., hollywoodtheatre.org, on Monday, Nov. 19. 7:30 pm. $7-$9.