As the coronavirus outbreak continued to spread this spring, PHAME Academy—the 35-year-old Portland arts school for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities—went from planning 30 classes a term to being completely shuttered.

"When we had some campus coordinators calling and checking in on students, some of them were like, 'Oh my God, so glad you called,'" says Matthew Gailey, the school's director of arts and education. "But some of them were like, 'I'm glad you called, but don't ask me how I'm doing. Let's talk about classes.'"

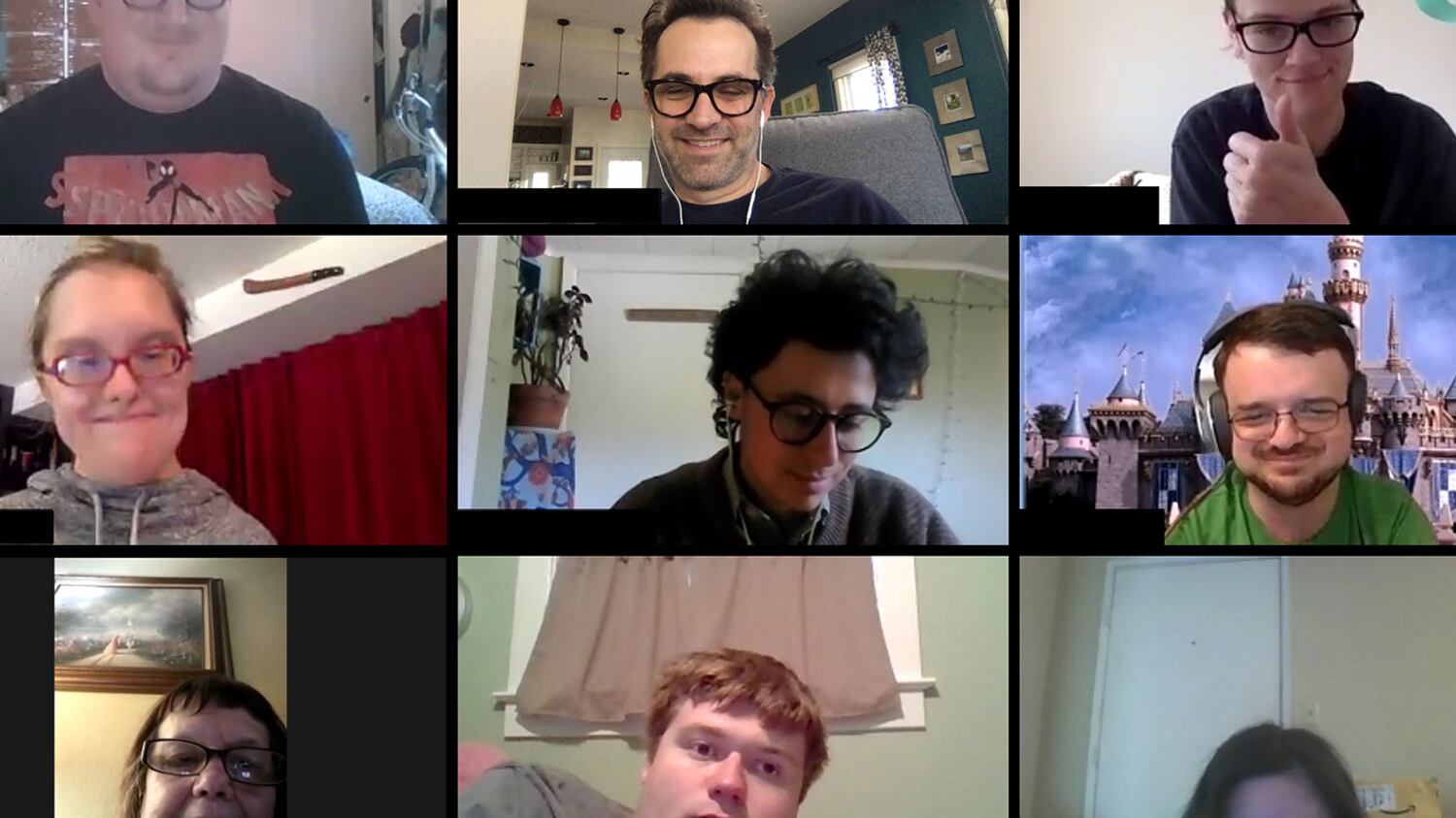

PHAME's staff did more than talk. In three weeks, they reconfigured the school so students could use Zoom to do everything online—from cartooning to singing "Lean on Me." While the nonprofit hasn't gotten back to offering its full load of courses, its essence has been preserved for students like Ashlie Parrott, who became involved with the school after she saw its 2016 production of The Wizard of Oz.

"It's pretty cool to connect with every single one of your friends who go to PHAME with you during the pandemic," says Parrott. "I think it's really important to stay connected."

Until the pandemic forced the major adjustment, PHAME had never offered online classes. But both staff and students made it clear they wanted the school to find a way to stay open.

"For us, art is always in the service of community," says executive director Jenny Stadler. "People with developmental disabilities are so isolated already that if they did not have PHAME, they would have taken a huge, huge hit."

Even though classes are back in session, they look anything but normal. For example, Zoom's time delay makes it impossible for choral students to sing in unison, so they instead practice with recordings. The shift has also allowed PHAME to expand its offerings. One addition is a radio drama course, which is taught by Stephanie Scelza and Gailey, whose initial disappointment over the students' choice to adapt The Lion King eventually gave way to enthusiasm.

"I have to say, it's pretty entertaining—the voices they're coming up with for the characters and the sound effects," Gailey says. "One of our students, if the script calls for ominous music, his job is to search his music library and come up with something and be ready to play that excerpt on cue. Then we have two other students who are teaming up—if we need a 'thwap' sound or a knocking or a rumble, their job is to find practical items in the house that can be used to reproduce those sounds."

PHAME's teachers have fought to sustain the communal spirit that makes the school indispensable to its students.

"I've incorporated a check-in into every class so we can talk about how they're doing, what they've been doing at home or wherever they're social distancing at," says Tess Raunig, a current teacher and former student. "I also let them know that it's not easy for me. I'm a very social person and it's hard on my mental health to not be going out and seeing people in person. I let them know we're all in this together."

Togetherness is built into the architecture of the new PHAME. The corridor where students used to hang out with campus coordinators may be off limits for now, but it lives on as a three-times-a-week Zoom session called CC Hallway that is both a time for socialization and a symbol of the PHAME community's endurance.

"A CC Hallway is where you get to hang out and it's free," Parrott says. "You just talk about anything, or sometimes play some games."

While Zoom has allowed PHAME to reach people outside Portland's city limits, some of the school's students have disabilities that prevent them from taking online classes. But for the 66 students who remain, those sessions offer ways of coping with life during a global health crisis.

"I have one student who wrote this parody song about COVID-19 and about having to stay inside and how they wanted to see their friends," says Raunig. "I'm so grateful that PHAME took this online idea and ran with it. I'm so grateful I get to see my colleagues and my students."