The first time Muriel Lucas, the mastermind behind Portland pop-up screening series Church of Film, saw Sambizanga, it left them shook.

"It was so different than every political film I've ever seen," says Lucas. "I love radical cinema, and I watch a lot of that big, legendary, guerrilla-inspired cinema, but a lot of it just frustrates me, bores me. Some of it's terrifying in its patriarchal, authoritarian bent."

Released in 1972, Sambizanga was written and directed by French filmmaker Sarah Maldoror, who died from COVID-19 complications in April. Set in colonial Angola, Sambizanga follows a wife searching for her husband, a liberation fighter who is imprisoned and tortured by the Portuguese secret police. Even though it is by far her most famous work, the drama has never been distributed in the U.S. In fact, much of the pioneering director's oeuvre remains largely unknown, but Lucas is hoping to change that by translating a handful of Maldoror's films for the Church of Film's streaming service, Church of Film TV.

"I didn't have a complete picture of her as an artist," says Lucas. "I thought of her as this militant, great political filmmaker. You don't often get—unless you get to see a person's whole body of work—what they're actually fascinated in, what they really want to say as an artist."

The daughter of a Guadeloupean father and French mother, Maldoror was born in 1929. She co-founded France's first black theater company, Les Griots, and got her start in film working as an assistant on the 1966 anti-colonial classic The Battle of Algiers. She went on to become one of the first women to direct a feature-length film in Africa, and developed a collection of more than 40 shorts and full-length films during her lifetime.

According to Lucas, the reason Maldoror's work is often overlooked is clear.

"The answer's pretty obvious: She was a black woman making political cinema," says Lucas. "This is not a market that capitalist markets are interested in. Obviously, she had a hard time getting production money."

Despite Lucas' love of Sambizanga and talent for digging up obscure movies, it took them years to find good-quality versions of any of Maldoror's other projects. Last month, however, Lucas was able to add new English subtitles to three of Maldoror's lesser-known works, all of which are streaming for free on Church of Film's Vimeo page.

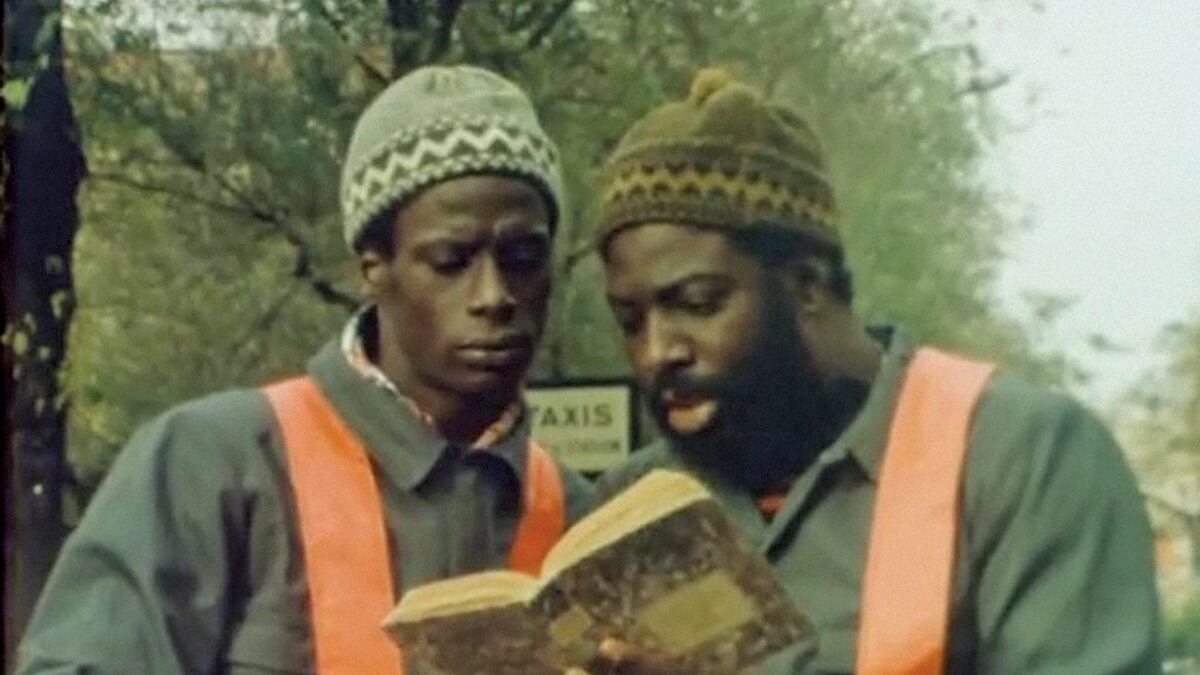

The trio stand out for their lightheartedness and realism. There's Miró, peintre, a 1980 documentary short about an exhibit by Spanish painter Joan Miró. In Scala Milan A.C. (2003), a group of French teenagers make a film about their neighborhood in order to win a trip to Milan—and end up enlisting jazz legend Archie Shepp for help. The 1981 made-for-TV feature Un dessert pour Constance follows Bokolo (Sidiki Bakaba) and Mamadou (Cheik Doukouré), two Paris street sweepers who enter a cooking quiz show in an attempt to win money so their terminally ill friend Bruno (Elias Sherif) can fly home to Senegal.

Translating those works required what Lucas calls "internet archaeology," or digging through film forums, which eventually led to a Vimeo page that featured Un dessert pour Constance with Spanish subtitles. They weren't well synced, but close enough to work. After securing that transcript, Lucas could start translating the dialogue to English.

"This is a French film, they translated it to Spanish, I translated it to English," says Lucas. "It's a game of telephone sometimes."

A former Latin teacher who took French in college, Lucas often retools subtitles for Church of Film screenings, but the Maldoror translations were a substantial undertaking. For instance, in Scala Milan A.C., the actors often use slang. And the cooking vocabulary for Un dessert pour Constance posed an extra challenge given the deliberate absurdity of the dishes: a recipe for "squabs" that Mamadou memorizes for the quiz show requires two partridges, a bottle of white wine, sirloin steak and a whole cup of gelatin. Lucas consulted native French speakers at times, but most of the effort consisted of Lucas sitting in front of a computer screen, sifting through each word.

"One of the weirdest, most intimate ways you can know an artist is just by picking apart a work line by line," says Lucas. "That's what you have to do with subtitles."

Watching the three works, Maldoror's fixations begin to emerge: how lives are influenced by chance, how the working class shapes culture, and the optimism of mutual aid. There are uniquely humanist moments, like when Maldoror zooms in on the smiling faces of children in Miró, peintre as they enjoy some truly bizarre performance art. Scenes scattered throughout Un dessert pour Constance show Mamadou and Bokolo joking aimlessly together during breaks, slyly giggling at their boss, who treats street cleaning like a patriotic calling, while laughing off the white Parisians who respond to the duo's frivolity with unwelcoming glances.

But even that humor has a radical bent. At one point in Un dessert pour Constance, after they've paid for Bruno to return to his family, Mamadou and Bokolo share a moment of reflection. Bokolo says what's important is that Bruno is gone. "No, brother," replies Mamadou. "The important thing is never laboring in the midst of loneliness and contempt."

A film this layered yet watchable, and so kind to its characters, should never be lost to the mass grave of made-for-TV movies. Fortunately, Lucas believes there will always be fans eager to unearth these treasures.

"It really is up to scrappy film enthusiasts to often track these down and do the work," says Lucas. "Because the capital channels are not going to work for this cinema. It doesn't work for a lot of cinema."

SEE IT: Miró, peintre, Scala Milan A.C. and Un dessert pour Constance stream for free on Church of Film's Vimeo page.