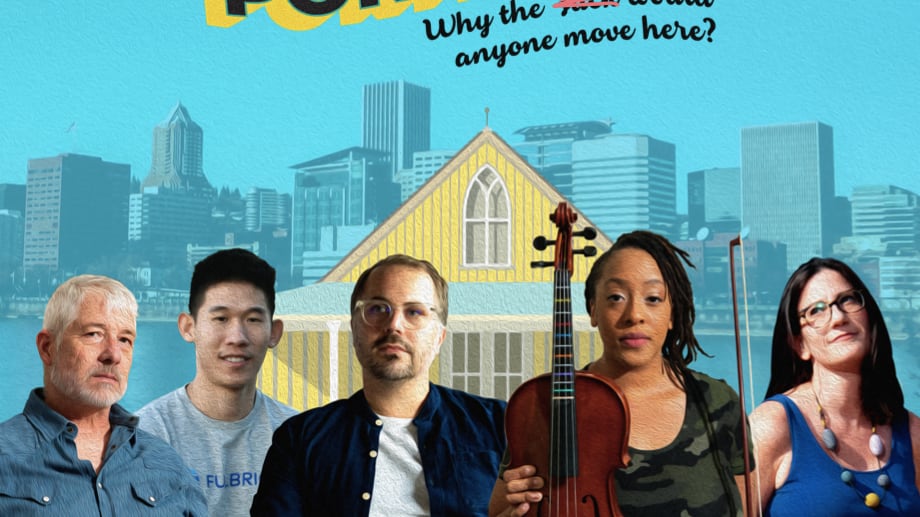

COVID, heat domes, downtown protests, Proud Boys, homeless people sleeping on the streets. Those of us who already live here may not be going anywhere soon, but move here?

I’ve lived in Portland for 13 years.

In many ways, I have seen Portland at its best: its jubilant Pride parades, its rose-filled parks, its ever-growing bike lanes, its food carts becoming brick-and-mortar restaurants, its cultural enclaves pulling together for mutual aid.

However, my ankle is permanently bruised from a ricocheting munition that hit me on New Year’s Eve while I was reporting on a protest downtown. And during February’s ice storm, houseless people built a fire in an oil drum that filled my building with smoke.

The popular Instagram account @portlandlookslikeshit may be one-sided, but it’s not without its piercing reality that this city seems to be somewhat out of control.

Yet people are moving to Portland.

According to Portland State University’s Population Research Center, the city saw a steady population increase through 2020. The numbers for 2020-2021 won’t be out until November, but data right now seems to suggest that while the pandemic may have slowed Portland’s population influx, it hasn’t stopped it. The city is growing.

We spoke with several people who have picked up stakes and moved to this city in the past 18 months. Renters and homebuyers. Students, teachers and designers. A scholar from Myanmar and a Black woman from Kentucky. We asked them all the same questions. Why Portland and why now?

They’ll tell you.

—Suzette Smith, Arts & Culture Editor

The Vegan Vlogger

Breann Vaughn has two businesses and attends college online. And she plays the viola. All she wants is a vegan dinner with no questions.

By Suzette Smith

“The cat is out of the bag,” Breann Vaughn says in her latest YouTube video. “We never came back from our honeymoon.”

She announces that a month ago she and her husband, Montez, sold most of their possessions and moved from Newport, Ky., to Portland. Vaughn arrived at Portland International Airport with a carry-on bag and her viola case. The couple found a small but bright apartment off Southeast Division.

Though she’s quick to describe herself as a reserved, shy person, Vaughn, who recently turned 30, has been vlogging on YouTube for over a decade—on subjects ranging from college tips (when she was in college) to styling tips for Black hair to how she makes vegan versions of many of her favorite dishes.

“I want to find a niche,” she sighs. “I guess if I have to encapsulate, it’d be lifestyle because the channel changes with me.”

Her following is a respectable 4,650 people. And her voice is wildly addictive, if ASMR is your slice of cake. Hearing this, she laughs.

“That’s been some of the most recent comments. They just wanted me to say certain phrases or just talk quietly for a long time. My husband was like, ‘You haven’t heard your voice?’”

The channel Allodyno was something she started with her twin brother, Bryson, a Portland rapper who goes by Bryson the Alien. They both grew up in Toledo, Ohio, but musical pursuits brought Bryson out to Portland in 2015.

Vaughn says she moved to Portland for Bryson. But also, she says, because of the opportunities she thinks she can find here. And lastly, the vegan community of Portland, which she already feels welcomed by.

“Every time we go into a restaurant and try to find a vegan meal, we’re talking to people who know what we mean and we don’t have to explain it,” Vaughn says.

In Kentucky, she found herself constantly explaining what veganism was, to the point where, just before they left for Portland, the couple found out their favorite restaurant had been serving them curry with oyster sauce in it for two years.

“They didn’t know how important it was for us,” Vaughn sighs.

The confusion over Vaughn’s animal- and eco-friendly principles also presented a barrier to her other business: a cleaning company, Shiny Vegan.

“Everything we tried to bring to Kentucky with our business—like using paper straws or reusable microfiber cloths—people had such a hard time understanding it there,” Montez says.

And while Vaughn is new to the homeless problem in Portland, she was charmed to see Portlanders leaving a store and giving their change to someone standing outside.

Between vlogging and filling out the paperwork to start up Shiny Vegan in Portland, Vaughn is also attending an online college to become a paralegal. And playing viola—which she’d been doing since fourth grade. Somehow she works all of it into a sort of harmony.

“Having a YouTube channel but also having a business, I just try to make them flow together,” she says. “I make videos about the hiccups I’m having.”

The Photographer Family Man

The Saputos moved from Brooklyn to Portland to reacquaint their 6-year-old daughter with the natural world. At first, it terrified her.

By Robert Ham

Finding an abundance of free time on his hands—as a result of the world grinding to a halt because of the coronavirus pandemic—photographer and graphic designer Tim Saputo and his wife decided to, in his words, “rethink what we wanted out of life.”

After shelter-at-home orders went into effect, Saputo and his family were stuck in their tiny apartment in Brooklyn for the better part of four months. His wife worked from home full time, so Saputo put an end to his freelance career to keep on top of the housework and serve as his young daughter’s pre-K teacher. “I wanted to make sure that we kept some degree of normality,” Saputo says.

But as the pandemic wore on, the prospect of remaining in New York—a city suffering one of the highest rates of infection and COVID-related deaths—became harder and harder to defend.

“It was just so claustrophobic and terrible,” Saputo, 38, says. “Everybody’s just so crammed together. New York has gotten increasingly hard for people, especially working families, to afford to just live there.”

So late last year, the Saputos pulled up stakes and ventured across the country, landing in Portland just as smoke from the wildfires overtook the city. Add in the ice storm a few months later, and the couple began to have some reservations about their decision to relocate here. But not enough to send them scurrying to the nearby state of California, where they both grew up.

“We both really missed the West Coast,” Tim says. “There’s a general sensibility that’s different than the East Coast, and we really missed being around nature. But we really didn’t want to live in California.”

Even after you spend a small amount of time with him, Saputo feels like the kind of newbie that Portland should be attracting. As a designer, he’s brought a clean, modern style to promotional campaigns by Google and Squarespace, and he helped create the sleek look of Pax vaporizers.

As do most professionals in his field, Saputo also maintains a creative side hustle, as a freelance photographer.

His photography work is even more stunning than his design efforts.

Whether it’s a sneaky shot of Nick Cave onstage or a candid picture of his daughter, Saputo’s photos feel active and vibrant—even more so when risograph-printed in the pages of his self-published photo books.

Though it hasn’t even been a year since his arrival, Saputo already talks like a native. He’s found his favorite haunts in Woodlawn, like the P’s & Q’s Market, and expounds on the greatness of Eem and Ranch Pizza. But he’s also wise enough not to overstep when WW starts quizzing him about how it feels to see the homeless encampments around the city.

“I honestly don’t know what to say, because it’s so complicated,” Saputo says after a small pause. “And I don’t know enough about local politics yet to be able to say that one person has a better solution than another. There’s so much that I don’t know still.”

What Saputo can speak about with confidence is how much better it feels for him and his family to reconnect with the natural world after years cloistered in an ultra-urban environment. Taking a trip to the woods, for example, used to be an all-day nightmare that included renting a car and fighting traffic for three hours. Now, the Saputos are less than 20 minutes away from a forest hike or camping trip.

That said, their proximity to nature was a bit of an adjustment for the youngest member of their family.

“When my daughter first got here, a plant would blow in the wind and she’d be like, ‘Aaaah!’” Saputo says, laughing. “Now she’s off climbing trees.”

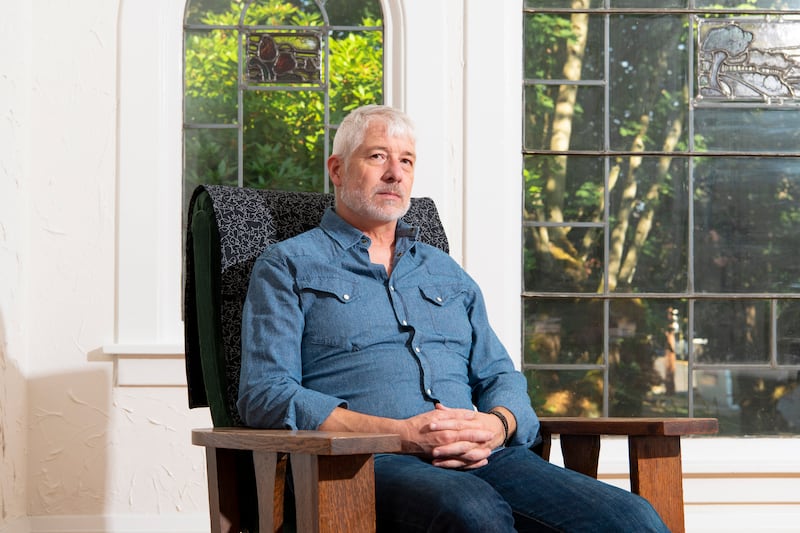

The Well-Traveled Rocker

Camper Van Beethoven bassist Victor Krummenacher toured Portland for decades with his many bands and music projects. Now he’s here to stay and climbing back onstage with Eyelids.

By Jason Cohen

When Camper Van Beethoven bassist Victor Krummenacher, 56, stepped off the stage of the Aladdin Theater in January 2020, he expected to be back in Portland soon.

Third Mind, a new band he’d formed with longtime collaborator and guitarist David Immerglück, was scheduled to play Mississippi Studios in April. There were talks of solo shows and sharing a bill with Portland singer-songwriter Casey Neill to support Krummenacher’s ninth album, Blue Pacific. Lastly, after leaving his longtime home of San Francisco and his designer job at Wired for the freelance life, Krummenacher was also keeping tabs on Portland real estate.

Needless to say, most of that didn’t happen—except he did move to Portland.

Krummenacher spent the first four months of pandemic lockdown living with his mom in Riverside, Calif. Then he bid on a house in Portland’s Alameda neighborhood sight unseen—other than a Redfin listing and an iPhone tour. He got the keys in July, around the same time Department of Homeland Security officers showed up at the ongoing demonstrations in Chapman Square.

“I was eating tacos at some kind of yuppie taco place,” Krummenacher remembers. “And there’s like tear gas. [The servers] came up like, ‘You need to leave. We’ll just put your margarita into a to-go cup.’”

Krummenacher was drawn to Portland by the same things many people are: its fusion of big-city culture and proximity to nature and, yes, its progressive mindset.

He says he knows enough about Portland’s history to understand the city’s racist legacy, but “part of the benefit of having a liberal-minded culture is that at least you have awareness,” Krummenacher says. “People are willing to actually look at things. There are a lot of communities here that look out for each other, and that is good. Because if it gets gnarlier, at least you have some people who will be fighting good fights.”

Krummenacher doesn’t buy into the “Portland is dying” hype.

“On some levels, this town is pretty messed up,” he says. “And then, on other levels, when I hear people complain, I’m like, ‘Have you really spent time in Los Angeles? Have you really spent time in the Bay Area?’ Because yeah, the homeless thing is bad here, but it’s really bad in the Bay Area. It’s horrific in Los Angeles. There are plenty of places in Los Angeles where you can see everything you see in Portland, sometimes on a larger scale. It’s just: America.”

Krummenacher describes himself as “not completely anti-police, but yeah: Defund the shit out of it and make it more accountable.” He also didn’t have to live here long to diagnose the city’s basic problem. “It would be nice if the mayor wasn’t a police chief,” he says. “That’s just super not OK, on so many levels! The commission thing is stupid. The city should just rip off the Band-Aid and get a real city council. That would really help things I think—more than people can imagine.”

The other reason Krummenacher made Portland home was that he already knew a ton of people, going back to the ‘80s heyday of college rock. Quasi’s Sam Coomes, Jackpot Recording Studio’s Larry Crane and Janet Weiss were friends. Camper Van Beethoven tours forged connections with R.E.M.’s Peter Buck, the Young Fresh Fellows’ Scott McCaughey, and Dharma Bums’ John Moen and Jeremy Wilson. Much more recently, Krummenacher has shared a bunch of bills with Moen and Christopher Slusarenko’s band Eyelids.

During the pandemic, Krummenacher couldn’t see those friends. He also lost several back in California to the coronavirus and couldn’t help but be reminded of living through the AIDS epidemic as a gay man in San Francisco in the ‘80s and ‘90s. He spent most of his days walking alone, sometimes going as far away as Mount Tabor (a solid 9- to 10-mile round trip), and home recording a new solo album, Silver Smoke of Dreams.

Still unable to play live or socialize when the second lockdown hit in the late fall, Krummenacher seriously considered undoing the whole thing and heading back to California. But then he got vaccinated and also got a call from Moen and Slusarenko. Their longtime bassist Jim Talstra (another former Dharma Bum) was leaving Eyelids; did he want to join the band?

“I like those guys personally a lot, I like their music a lot, and I haven’t really played music like that—the power pop thing—much,” Krummenacher says. “They have an audience and I can be in front of people and, also, they’re thoughtful. They think about what they want to do and how they want to do it. It means something to them. That’s important now.”

Pandemic protocols permitting, Krummenacher will see a stage again very soon. The new Eyelids lineup makes its official debut at Mississippi Studios on Oct. 16. “At this point,” he says, “really all I want is just to continue to play and be creative.”

The Student Far From Home

Jordan Paing came to Portland to study historical preservation, only to see his home country deteriorate from afar.

By Justin Yau

Two months after Jordan Paing moved to Portland, there was a coup in his home country of Myanmar.

He found out on social media, seeing a Jan. 31 post from a friend back home. Paing called and they told him officials of Myanmar’s pro-democracy government had been arrested by the Burmese military.

“I tried to text everyone,” Paing explained. “You know, to wake up and be prepared, since it was 4 in the morning in Myanmar. I finally reached my mother after an hour and a half.”

Two months earlier, Paing, 25, stepped into the cold December air outside Portland International Airport, it was his first time in the U.S., let alone Portland.

At first, he lived in the Pearl District. Despite the street demonstrations on a near-nightly basis and the dire December-January spike in new COVID cases, what bothered Paing the most was the plight of the homeless that was the backdrop of his new neighborhood.

“I am saddened by the poverty and the vulnerability of drug addiction and mental illness in the unhoused community,” Paing says.

Paing eventually moved to Northeast Portland, where the issue is less apparent. Still, in his eyes, the city’s leadership should put forth more effort to find solutions to end the homelessness epidemic.

“I’ve seen them yell at people,” he says. “I was shocked by the yelling, but I didn’t really feel unsafe.”

An architecture student from Yangon, the capital of Myanmar, Paing moved to Portland to complete a master’s degree in historical preservation at the University of Oregon. “I want to learn about the preservation of historical urban structures,” Paing says. “I want to be able to take these skills back to Myanmar.”

Though initially drawn to the East Coast for its much older cities, Paing ended up choosing Portland because of a scholarship he received. He also liked that the city’s interest in environmentalism aligned with his own.

Much of Paing’s time here in Portland is—ironically enough—spent in Zoom classrooms, the COVID-era nightmare of higher education right now.

He also can’t help but be drawn into Portland-area demonstrations with other like-minded members of the local Burmese community.

“I want to organize more food fairs, expand Burmese food fairs to the Portland community.” Paing says. “Food is a very subtle cultural product. You can touch people of other cultural backgrounds with food.”

Paing has a big passion for food—he likes eating it as much or more than making it—and hopes to enjoy more of the city’s rich food culture, carts and eateries before finishing the final year of his program.

“I’m looking forward to Portland’s night scene, the bar scene, the live music,” he says.

As society opens up again and before he decides whether or not to return to Myanmar, Paing has a chance to experience the Portland he’s heard so much about.

“Everything is up in the air right now,” he says, a twinge of hope and uncertainty in his voice.

The Wry Remote Teacher

Comedian Rachel Rosenthal spent quarantine teaching Facebook employees how to communicate—with theater!

By Suzette Smith

“More people have warned me about locking my car and hiding my valuables here than in 10 years of living in New York,” Rachel Rosenthal says.

Rosenthal has a big-city vibe about her. She grew up in Connecticut, and her parents, New Yorkers themselves, frequently encouraged her to take the train into the city alone.

People who weren’t from there were like, “Isn’t it dangerous to go to the city?”

The irony is that Rosenthal, 42, is no stranger to theft. Though she’s a comedian and improviser, she’s also NPR famous for a particularly jaw-dropping episode of This American Life called “The Perils of Intimacy” in which she unpacked the experience of having her romantic partner steal her identity, repeatedly—for years.

Perhaps that’s why it’s so nice to hear that things are going well for her. She’s married—to another comedian-performer, Sam De Roest. They have an adorable podcast together and an adorable dog. And since August of 2020, she lives in Portland.

Despite the theater and comedy scene tanking hard last year, Rosenthal’s career as a corporate improv teacher has, strangely enough, boomed. She’s been teaching workshops, primarily for Facebook. “They’re a little startup. I don’t know if you’ve heard of them,” Rosenthal jokes.

“When the pandemic hit, and we really began to get a sense of the scope, I thought I was going to be making zero income.” Rosenthal says. “What I’ve found is that companies seem to need connection now more than ever.”

Teaching remote improv theater to tech employees suited Rosenthal fine. She didn’t want to try to innovate over Zoom. “My art form is completely based on eye contact and in-person communication,” she says. “Trying to perform improv on Zoom lacks all the things that make it fun.”

Instead, she started a podcast with her husband called Sam and Rachel’s Generation Gap, built around the 12-year difference in their ages—her husband is 30. They take turns explaining two pop culture items every episode, one from her childhood and one from his.

The episodes are funny and warm and include moments like De Roest interrogating an extremely stoned Rosenthal, in transit on the subway, over the makeup of the fellowship of the nine. She guesses, “Sauron?”

In August, the pair moved to Portland, undeterred by reports of ongoing protests—actually inspired that a city would care so much about Black lives.

“We were living in a very small apartment, a fourth floor walk-up, with a galgo (a Spanish greyhound). It was August, so every day was like 100 degrees. Sure, we knew about the protests, but there was just so much other stuff going on.

“At that point, protests weren’t going to stop us. We needed to get somewhere we could live and breathe and have two people work from home for an extended period of time.”

Living in outer Southeast, Rosenthal maintains a view of Portland that consists mostly of flowers, gardens and friendly neighbors. When hers saw two New Yorkers struggling to figure out their garden, they walked over and gifted them a pair of shears. “She was like, ‘Here, I just picked these up for you.’”

Not everything is roses, though. Someone recently stole the catalytic converter from a car owned by one of Rosenthal’s visiting friends, effectively stranding the car for weeks: “She had to go back to Ashland. She has no way to get to work right now. It’s terrible.”

“You can tell that downtown isn’t what it used to be,” Rosenthal says. “I don’t attribute that to the pandemic and protests. I might attribute that to a city that was booming and grew too fast.”

For all its troubles one year in, the magic Rosenthal felt when she moved to Portland is still part of her everyday life.

“Just walking my dog every day in Southeast, I stop to smell flowers every day. I don’t want to get sick of it, and I don’t want to get over it. Now that things are opening up, I feel like I just got here.”