Though Todd Haynes had never helmed a documentary before agreeing to direct The Velvet Underground for Apple TV+, the celebrated filmmaker and longtime Portland resident has a long history of expanding the parameters of musical biopics.

After his 1989 debut, Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, a surprisingly affecting experimental short that retold the singer’s tragic demise through the use of Barbie figurines, his 1998 bravura glam romp Velvet Goldmine was a thinly veiled fantasy biopic about David Bowie, while 2007′s critically adored I’m Not There examined the legacy of Bob Dylan, who was portrayed by six different actors.

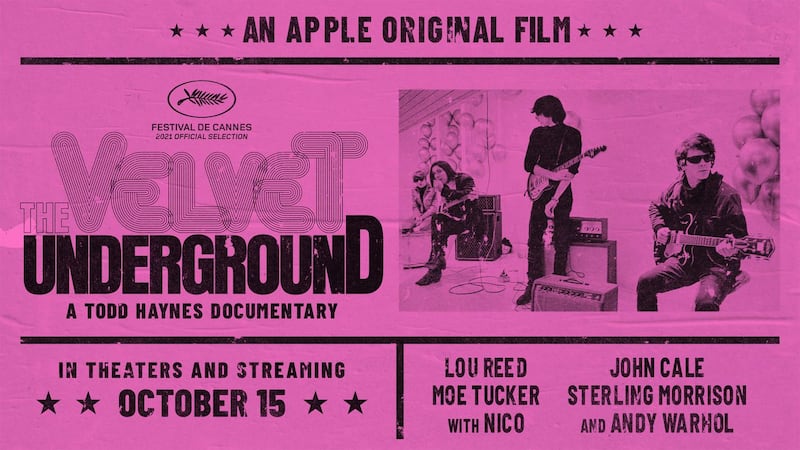

Set against Haynes’ more fanciful docudramas, The Velvet Underground seems almost a comparatively straightforward evocation of the Velvets—an enormously influential late ‘60s art-rock troupe that never troubled the charts yet inspired the style, tone and artistic ambitions of a burgeoning alternative nation. Interspersing what little footage exists of their stint as house band for Andy Warhol’s Factory alongside interviews with surviving members and associates, Haynes and his editors pour an unending deluge of imagery cribbed from fellow travelers’ experimentalist cinema into a thoughtful fever dream that is meticulous, ecstatic and very much alive.

Calling from a hotel landline during a press junket just days before the documentary’s Oct. 15 premiere, Haynes spoke with WW about his breathtaking new picture.

WW: How did you get involved in the film?

Todd Haynes: The project started when David Blackman—he runs Universal Music Group’s film and video component—asked if I would be interested in directing a documentary on the Velvet Underground. After Laurie Anderson handed over the Lou Reed archives to the New York City Public Library, they started to talk about making a Velvets doc in a way that hadn’t really been done before by a director she might feel comfortable approaching, And so they came to me.

Your response?

Oh, it was a yes! Completely. Even though I’d never made a documentary before, I was absolutely interested and knew a few things right away. The Velvet Underground hadn’t any traditional visual materials like other bands in terms of concert footage and promotional interviews. Instead, what they had would be found in the films of Andy Warhol, and they’re some of the most beautiful photo archives of the 1960s.

Did you have a preconceived idea in mind about structure? Was it built around interviews or footage?

The process began with interviews I conducted in 2018 with filmmaker Jonas Mekas—basically, the godfather of American avant-garde cinema—because he’d just turned 97, and I wanted to make sure that we had him in the film. He’s a seminal figure to film culture and the culture of the 1960s at large, which this film explores fully, and around which the Velvet Underground played a role as catalyst. Then we went on to [Velvet founding member] John Cale, whose interviews were really the centerpiece, but I didn’t want the film to be just driven by interviews, even though the interviews we got were extraordinary. I didn’t want talking heads telling us why the Velvets were important. I wanted the film, as much as possible, to allow you to discover that for yourself. I chose to interview the people who were there and exclude all of the countless people who came after.

It seems like the band’s recordings were just teased early on through snippets.

That was about exploring the sources of the music and how that music came into being from people like John Cale and Lou Reed, whose backgrounds were quite different, and ultimately bringing in Sterling Morrison and Maureen Tucker. The music is something that we wanted to excavate for the viewer—to, ideally, make you feel like you were hearing it afresh—and that’s not easy to do with music so well known that has, by now, entered the canon.

Almost half the movie goes by before we hear a full track.

That’s true. It takes about an hour to hear the first Velvets song “Venus in Furs” with the Lou Reed vocal. How long that takes—and how much you get into the ideas that were circulating in the 1960s—was always something I think we were all trying to protect. These were people who were very interested in breaking orthodoxies and changing the accepted conventions of music-making and art-making and filmmaking. That’s what defines this period as so distinct and extraordinary.

The Velvet Underground were deeply affected by the filmmaking, the image-making, the fluidity of New York City’s creative community. They had a unique relationship with this massive archive of avant-garde films, and I leaned into the visuals. I wanted the film to be driven by the images and the music and to try as much as possible to have the interviews support a more immersive, visceral experience for the viewer. Watching the film should almost feel like you are intuiting the story, not just being told what had happened—something that you could dream through and lose yourself inside. Let the images and the sounds guide your experience.

SEE IT: The Velvet Underground streams on Apple TV+ and screens at Hollywood Theatre.