Katherine Dunn saw broken and twisted things, wrapped them in her words, and made them beautiful.

A boxer’s bleeding cuts. A nightclub crawling with slurring drunks. A boy born with flippers for arms and legs, who sweet-talks his cult followers into sawing off their own limbs.

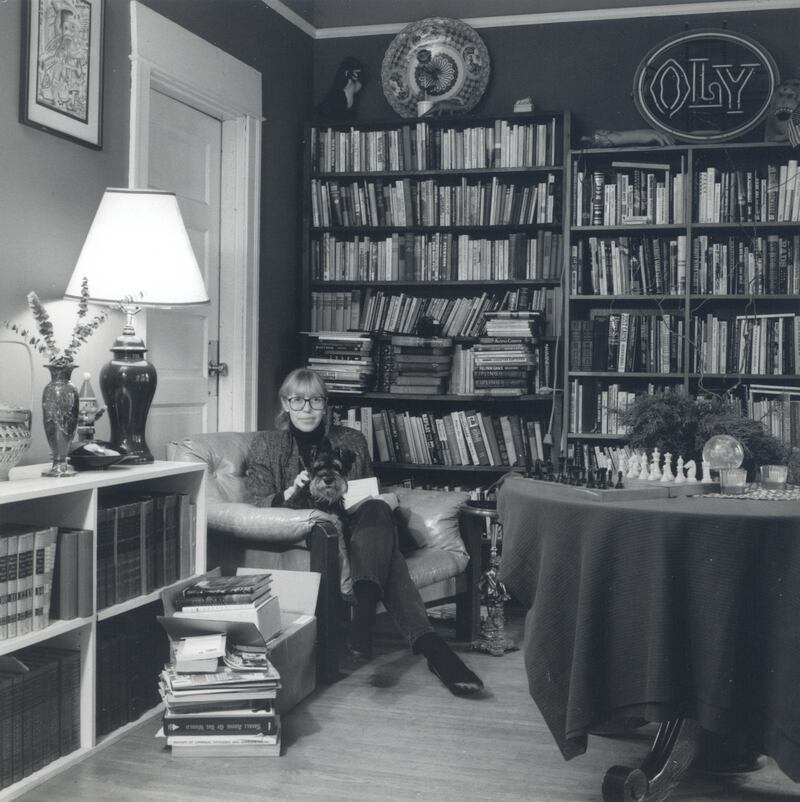

Dunn gained an adoring band of fans with Geek Love, the 1989 novel about a family of willfully mutated circus performers that will endure as her literary feat. The book became a phenomenon, taking Dunn from being a single mother working three jobs in Northwest Portland to the matriarch of Portland’s authors and poets.

Yet her singular talent—for fearlessly probing what others wished to skirt—extended beyond a single book.

“She believed the job of a writer is to tell the truth—not the truth that Aunt Mabel wants to hear, not the truth that will sell books,” says Portland author Rene Denfeld. “She always said she was waiting for a male writer to write a memoir that was not about all the women he’d slept with, but about having a problem with premature ejaculation.”

She could, as the boxing trainers liked to say, write a bit. Essays, reportage, humor squibs, novels: Dunn moved fluidly from one to another.

For a time, she became the nation’s only female sportswriter covering boxing. From 1984 to 1992, she wrote a column in Willamette Week, the Slice, that answered reader questions ranging from the size of Forest Park to the shape of an opossum’s penis. She never published another novel after Geek Love, yet never stopped writing its follow-up: She was working on her next book until earlier this year.

Dunn’s death May 11 at age 70 from lung cancer robbed Portland of one of its finest writers and most inimitable characters. Those she left behind have been wistfully eager to describe her mettle, generosity and vitality—her ability to make life an adventure and take others along for the trip.

Susan Orlean, The New Yorker writer and author of The Orchid Thief, who worked alongside Dunn at WW in the early 1980s, recalls Dunn wrangling the newsroom into attending boxing matches. “She finally convinced me to go,” Orlean says, “and I went imagining I would have my hands over my eyes most of the time and my fingers in my ears.”

Instead, Dunn talked Orlean through each round, explaining the fighters’ jabs and footwork until the other writer grew fascinated, then entranced.

“It was in real time, what her writing was like,” Orlean says now. “This pure conveyance of a really brilliant take on the world, on emotion, on human frailty, on striving and failure, and she really made it make sense and made it beautiful.

“She was, I’m sure, punching me in the shoulder saying, ‘See, I told you. I told you you’d like it.’”

By the time Geek Love made her a cult figure, Dunn was 43 years old. To her friends and fans, her past was a mystery, which she fiercely guarded.

“She was such a private person,” says former WW reporter Susan Stanley, who remained a close friend. “I could tell you some raucous stories, but I won’t.”

Dunn was born in Garden City, Kan., in 1945. Her mother, Velma, hailed from Velva, N.D., where she later returned to tend cattle until she was 98. Katherine’s father left before she turned 2, and Velma Dunn married a gentle giant of a car mechanic from Puget Sound. The family moved westward, picking fruit and eventually settling in the Portland suburb of Tigard.

In her 2009 collection of boxing writing, One Ring Circus, Dunn recalled walking through baby boomer neighborhoods, listening to the sound of prize fights playing on so many radios she could “walk block after block and never miss a round.”

She showed little nostalgia for her childhood. “That post WWII America was a rough place, as I recall,” Dunn wrote. “Racism and sexism were insistent and institutional. Spousal battery was condoned. The smacking and whipping of children in school and at home was expected. Gangs were common. Brawls boiled up in streets, playgrounds, taverns and workplaces.”

Her youthful memories usually surfaced in jokes. Former WW contributor Mark Christensen says Dunn would joke she didn’t have money for booze or drugs as a young person, so she would float in Tigard’s Fanno Creek like Ophelia, hoping to catch a bug that would give her a high. “She had a good sense of humor,” Christensen says, “but I also think maybe she did that.”

Dunn attended Portland State University for a semester, then received a full scholarship to Reed College. Her son, Eli Dapolonia, says Dunn was thrilled to attend an elite private school after her hardscrabble childhood. “Other kids in college would complain about the cafeteria food,” Dapolonia says. “She thought it was the best food she’d ever had.”

In 1967, she dropped out of Reed to travel the world with a man named Dante Dapolonia, whom she had met on Thanksgiving break in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco.

She wrote a novel, Truck, in Spain and a second, Attic, on the Greek island of Karpathos, and gave birth to Eli in Dublin in 1970. (In 2014, Dunn told Caitlin Roper of Wired that she wanted to make sure Eli was born outside the U.S. so he couldn’t be drafted: “Plus, Irish medicine is good, totally free, and the doctors speak English.”)

Dunn returned to Portland as a single mother in 1975, lured by the prospect of enrolling her son at Metropolitan Learning Center. Dunn found a walk-up apartment along Northwest 22nd Avenue and looked for work in the Alphabet District.

She began a typical day at 6 am, serving breakfast at Stepping Stone Cafe, where her customers included then-Trail Blazers center Bill Walton. She finished it at Northwest 21st Avenue dive bar the Earth, working until last call at 2:30 am. She later recalled having a female patron punch her in the face, and a biker nearly slashed her throat.

“You can’t be a girl behind the bar,” Dunn told WW in 1983, “you gotta be a woman. When the guys come in there to get sloshed, you must—just by your demeanor—remind them that they are now a guest in your home. That’s one of the advantages, though, of being a woman in a situation like the Earth’s. Even most of the wildest roughnecks in town are inclined to behave themselves if a female is in charge.”

Her other gigs included house painting, topless dancing, and hosting a radio show on KBOO-FM, where she read short stories aloud. (The latter two jobs made their way into Geek Love, where they became the professions of the mutated Binewski children.)

Somehow, she still found time to write.

On Nov. 24, 1981, Dunn’s byline first appeared in Willamette Week, a publication she would later describe as “a small alternative newspaper operating on one wing and a lot of elbow grease in a medium-sized town in the mildew zone.”

Her first article was a book review of Stephen King’s Cujo. (She was a huge fan of King’s.)

She soon turned to boxing, a sport she encountered through her first husband, Peter Fritsch.

The ‘80s were the golden age for boxing in Portland. The riverfront Marriott Hotel was the location of several high-profile matches featuring the likes of Charles “Machine Gun” Carter and Golden Gloves champion Andy Minsker. Boxing was largely shunned by The Oregonian, and Dunn seized the opportunity to fill the void in coverage.

She even persuaded cash-strapped WW Editor Mark Zusman to send her to Las Vegas to cover “The War,” the world middleweight championship match between “Marvelous” Marvin Hagler and Thomas “Hitman” Hearns in 1985. Her coverage began: “The high-voltage zing of a big fight is legendary. No Hollywood premiere, no Broadway opening, no ticker-tape parade draws so widely and deeply from the glitter heart of America. Stars and pimps rub satin shoulders. Tycoons and bricklayers, high-priced hookers and righteous socialites, all flaunt their glad rags in identical excitement.”

Dunn would later host parties at her home to watch pay-per-view boxing—a coveted ticket among Portland writers. “Her knowledge of the fight game is astronomical,” says Larry Colton, a former writer for WW and author of five books who went on to found the literary festival Wordstock. “It was like getting to watch a baseball game with Vin Scully.”

In 1984, Dunn started a weekly column called the Slice. She answered reader questions on such pressing topics as why men have nipples, who was scrawling “Jesus Saves” graffiti across Portland, and whether George H.W. Bush claimed to have had sex with Ronald Reagan. (Yes, but Bush had misspoken: He meant to say “successes.”)

In the WW newsroom, then located at the west end of the Burnside Bridge, Dunn was a fixture and den mother—older than both the editor and publisher, she attended the weekly staff meetings even though she was a freelancer. (She later spent time as WW’s arts editor.) A former staffer recalls her carefully weighing how to approach the fallout of a political scandal, suggesting how to angle the story sensitively. “Or,” she concluded, “you could bury the bastard.”

“She was not afraid of being against popular opinion,” Denfeld says. “If she were around in the era of social media, she might have gotten into trouble.”

Dunn often sported a button reading, “Sluts From Hell” and another pin that read, “The Meek Shall Inherit Shit.” She announced herself with a loud, throaty laugh and a cloud of cigarette smoke. She rolled each cigarette herself.

“She wore oversize glasses that seemed to magnify her gaze—you really felt like she could see through you,” says former WW reporter Chris Lydgate. “She smoked like a chimney and swore like a sailor. In print, she was devastating—the undisputed master of the sucker-punch sentence. I had never met anyone remotely like her, and never will again.”

Christensen recalls walking in Washington Park with Dunn sometime in the 1980s, talking about her son. “Could you deal with kids the same way people at Washington Park deal with the roses?” she asked. That idea—which Dunn later told Wired she hatched in the late 1970s in the same Washington Park rose garden—became the biologically engineered Binewski children of Geek Love, whose parents breed circus freaks by ingesting cocaine and insecticides.

Dunn told Stanley, her WW colleague, her idea and asked her to read a draft. Stanley was repulsed.

“I thought, ‘Oh, God, no,’” she recalls. “But I got into the book and thought, ‘She’s writing literature, and it’s just absolutely stunning.’”

Geek Love came into the world like many of the characters it describes—as a willful freak of a book.

When it was published in 1989, it was like no other book that existed, with a boldly stark design by fledgling artist Chip Kidd whose font and logo were marred by “mutations.” The book’s plot was equally odd, centering on the rise and fall of the Binewskis, who bred their own children to become their circus’s deformed human attractions.

But a quarter-century after its publication, Geek Love has evolved into a sort of Catcher in the Rye for much weirder kids—a morbidly funny tale of diabolical son Arty the Aquaboy and his messianic brother Chick, a soft-hearted kid born with both telekinesis and a fateful temper.

“There’s quite a legend about Geek Love,” writes author Chuck Palahniuk in an email to WW. “The Knopf imprint had just hired [superstar editor] Sonny Mehta. The vibe was nothing less than the excitement over Orson Welles arriving at RKO with complete artistic control. Mehta dazzled everyone and cemented his legacy by breaking out a novel written by a nobody (Dunn) with a cover by a nobody (Chip Kidd). That book made three careers: Mehta’s, Dunn’s and Kidd’s.”

Mehta recalls the preparations as exhilarating.

“It was a very, very exciting book to publish,” he says. “We had a great time working on the jacket—at least I did. The jacket was iconic for a book that went on to be iconic in itself.”

Dunn’s book seems uniquely suited to the ramshackle, almost deranged Portland of the ‘80s. But its exuberantly lyric swirl of beauty and disgust, sadness and uncommon wisdom has resonated far beyond our city. The book was published in 13 languages, including Finnish and Hebrew, and has never been out of print.

It has always inspired extreme reactions. The New York Times’ Steven Dobyns groused over the book’s “spectacle,” and the Orlando Sentinel publicly refused to review it, declaring that “the subject matter is too disturbing, the imagery too grotesque.” But The Seattle Times pronounced Geek Love “probably one of the most extraordinary novels of this decade.” It was a finalist for the 1989 National Book Award for Fiction alongside Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club (both lost to Spartina, by John Casey).

Richard Pine, Dunn’s literary agent, says Geek Love went against all conventional wisdom in publishing. “You had some outliers in South American literature,” Pine says. “But Americans weren’t writing this kind of book.”

Geek Love changed Dunn’s life. The book sold more than 400,000 copies, but it wasn’t the acclaim, the awards or the sales that made a practical difference.

It was the movie rights—sold over and over again, to such disparate figures as Tim Burton and Night Court star Harry Anderson. (Anderson, then a Macintosh pitchman, gave Dunn her first Apple computer as a gift.)

“All of a sudden, Mom had money,” Dapolonia says. “More money than she’d ever seen before.”

Dunn bought a six-bedroom house in the Alphabet District. She offered spare rooms to her son’s friends. She loaned money to colleagues, and mentored more Portland writers than we can list. She gave Palahniuk’s Fugitives and Refugees its title.

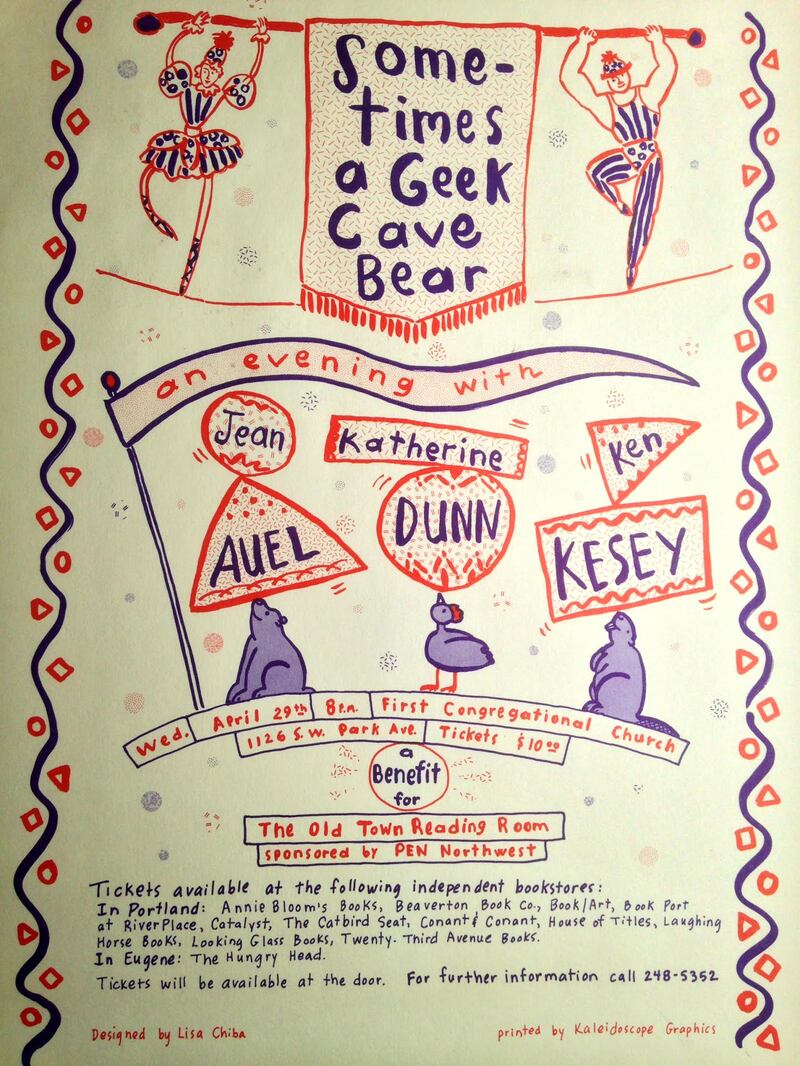

The newfound celebrity did not tame her. Angie Jabine, a former WW staff writer who remained close to Dunn, organized a benefit reading in 1992 featuring Dunn, Jean Auel and Ken Kesey. Dunn canceled at the last minute—Jabine recalls Dunn’s appearance was a casualty of her interest in sideshows.

“Supposedly, the fire marshal objected when she said she didn’t want to read but to demonstrate her fire-breathing, which she’d been learning for several years from an expert,” Jabine says. “That’s one explanation. The other is that she’d burned herself, and was in no condition to read.”

Dunn worked on a follow-up novel to Geek Love, a boxing saga called The Cut Man. The only portion that’s ever been seen is a short excerpt that ran in The Paris Review in 2010. “She made a lot of revisions,” Dapolonia says. “And when she died, as far as we know, she wasn’t finished.”

Dunn made few public appearances in the past decade—partly because she hated being fawned over, and partly to avoid questions about that long-awaited fourth novel. “She knew she would be asked about The Cut Man,” Colton says. “She actually went to Wordstock, just as a spectator wearing shades and a hat.”

In 2013, Dunn married her second husband, Paul Pomerantz—an old boyfriend from her days as a Reed College undergraduate.

This April, the cigarettes caught up to Dunn. The bout with lung cancer lasted just five weeks. She told almost no one—even close friends—that she was dying. She still wanted her privacy.

On May 13, Portland poet Walt Curtis mailed WW a letter, composed on a typewriter.

“My Gawd, I just heard that Katherine Dunn died,” he wrote. “I am saddened, stunned. I always felt that she was indestructible.”

In 1993, Dunn returned to the boxing ring. She started taking boxing lessons at Matt Dishman Community Center in North Portland.

Those lessons proved useful in 2009, when a 25-year-old woman tried to snatch Dunn’s purse as she carried a bag of Trader Joe’s groceries under her left arm, heading back to her Northwest Portland apartment.

Dunn didn’t let go of the purse. She didn’t drop the groceries.

Instead, until store workers arrived, Dunn used her right fist to repeatedly punch her would-be mugger in the face.

“She was quite happy about it,” Dapolonia says. “She was just mad she couldn’t use her left.”