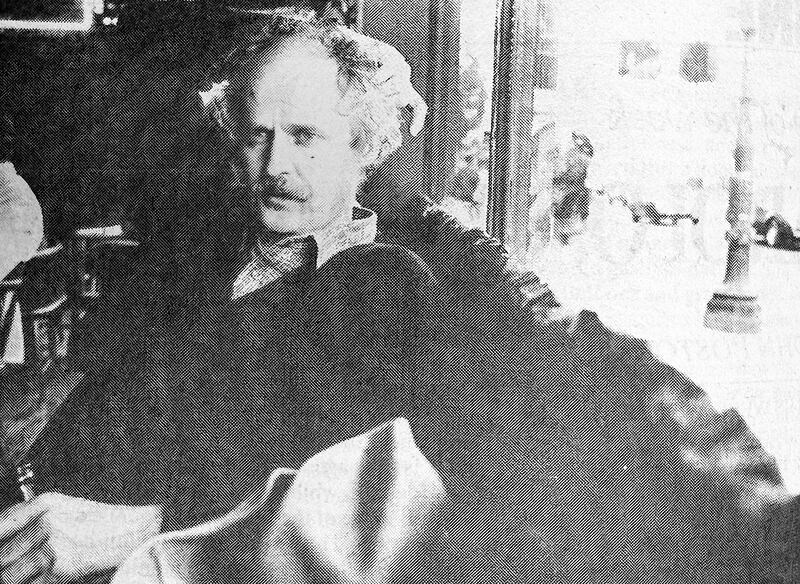

The streets of Portland are a little less electric this week. On Aug. 25, Walt Curtis died at age 82, after decades spent beguiling and confronting the city from its undercarriage. Curtis was a poet, his Beat-inflected verse both pastoral and lewd. But that designation hardly captures the role he played in the twilight life of the city, where he could materialize like an ancient mariner in the back row of readings, mustache bristling and hair on end as he harangued the speaker. Curtis will always be intertwined with a fertile moment in Portland’s arts scene in the 1980s, when the city’s writers and filmmakers began producing work of national renown. Among those works: Gus Van Sant’s first movie, a doomed romance called Mala Noche, based on an autobiographical chapbook Curtis wrote. We asked a few of the people who were there with Curtis to remember him. —Aaron Mesh, WW managing editor

Walt was one of the few Portlanders who truly resembled the ancient Greek poets—Hipponax, Anacreon, Diogenes—roaming around the Portland streets sharing his lyrical poetry on love, wine and revelry, getting held up on street corners engaging in witty and sometimes controversial conversations with people.

I met Walt on Penny Allen’s film Property—he was playing a leading character but slowly backed down from being the lead because it was too much work for him. Walt and Ken Kesey would give co-readings at hippie gatherings, or poetry readings in bars. Walt’s poetry and his stories, always edgy and pornographic, would freak out Kesey at times, too gay maybe, or too far out.

Walt and Kesey both had soft whispery voices like one would use while calming down a horse, a voice familiar if you grew up in Central Oregon—a voice you would hear when Walt read his poetry. Walt’s little finger on his left hand was cut off at one of the joints from cutting wood in a logging company—he was also a logger.

I asked him whether I could make his story Mala Noche into a movie, which concerned him at first. But then he generously agreed and helped on the shoot, bringing posters of the Schlitz malt liquor bull to hang on a wall decorating an old grocery store, or offering us his apartment as a location. It was a movie that got me going in the film world.

Thanks, Walt—very sorry to see you go. —Gus Van Sant, filmmaker

Walt made an unforgettable impression onstage, constantly moving, a page of his poems clutched in his hand, speaking directly to someone in the front row then shouting insults at someone in the back, then talking to himself, questioning what he had just said, smiling, saying yes, no while laughing heartily, then rumpling his unkempt pile of hair as if to erase the whole episode and start over. He was so funny! So outrageous! Even though I didn’t know him, I met up with him and asked him to play the principal actor in my first movie, Property. To play pretty much himself as the character who needed to be a reluctant activist, somebody who felt injustice was descending on his neighborhood and community, but someone who was entirely unsuited to organize a communal counteraction. Two people in one, yes, that was Walt, a fascinating, conflicted original. Good at assembling rebels but then, when the going got rough, good at agony, revealing his frustration as he mumbled with his hand over his mouth. For me, he was always lovable. —Penny Allen, filmmaker

Circa 1981: He drove a white 1960 Dodge Dart station wagon, the back jammed full of used books he’d sell to support himself. He’d do poetry readings at dive bars and taverns in Northwest Portland near the funky apartment building he lived in at 133 NW 18th Ave. called The Lawn, an old Victorian house that was converted into a maze of tiny apartments.

What struck 20-year-old me about him was that he had a poetic engagement with Portland that transcended any particular poem or painting of his. He knew and understood its people and flowers and history, and he found beauty and dignity in some of its most vulnerable citizens. It deeply impressed me that Walt devoted himself to his artistic engagement with the city. It was his career, his family and his lover rolled into one. In many ways, his example gave me permission to devote myself to filmmaking.

Years later, I interviewed him for Alien Boy: The Death & Life of James Chasse. Walt told a moving story of Nils, a friend of his with Tourette’s syndrome, being stopped by the police. Walt interceded on Nils’ behalf to avoid the possibility of the police misinterpreting Nils’ verbal outbursts as aggression. That to me epitomized Walt: speaking truth to power and sticking up for the oppressed. —Brian Lindstrom, filmmaker

In about 1988, at age 17, I went to Cinema 21 to see Allen Ginsberg read. The scent of wet wool and patchouli was thick in the balcony that night, and the opening act, Walt Curtis, blew my mind. I remember he read a poem about shopping at the grocery store that quickly went pornographic about fruit. “The bananas were like cocks!/The apples were like balls!” Something like that. But more so, I remember his wired patter. I remember so vividly him pausing between poems at one point and saying, “Look at us all in this room! We’re all sitting here so calmly! And it’s crazy, because we’re all gonna die! All of us in this room, we’re gonna die!” My teenage brain did the math and confirmed: It was true.

Allen Ginsberg came out soon after and played his harmonium and sang William Blake poems, which was lovely, but to me, that night belonged to Walt Curtis.

I never met Walt, though I saw him around for many decades after, and regarded him as an unapproachable celebrity. I remember seeing him at a Gary Indiana reading in the early ‘90s once. Gary finished his reading and offered himself for questions, and Walt immediately rose and introduced himself as the author of Mala Noche. Gary ended the Q&A there. He walked into the audience and hugged Walt, and they went off together, who knows where. I remember watching them leave and thinking, man, that’s the conversation I want to be in.

Thank you, Walt Curtis, for treating this town and this land as a poem unfolding. —Jon Raymond, screenwriter

MORE: Read a 1984 profile of Walt Curtis written by Katherine Dunn here.