While other journalistic outlets are still reeling from the pivot to video, The Nib is headed in a bold, old direction: print.

Last fall, the Portland-based comics publication, which has been online since 2013, launched its first print issue. Though the media in question are different, editor-in-chief Matt Bors says The Nib is branching out for the same reason other outlets do: economics. "With our readers and with comics readers, they still like having something in print," Bors explains. "It's just an economic model that's going to lead people to support us more than just asking for money online."

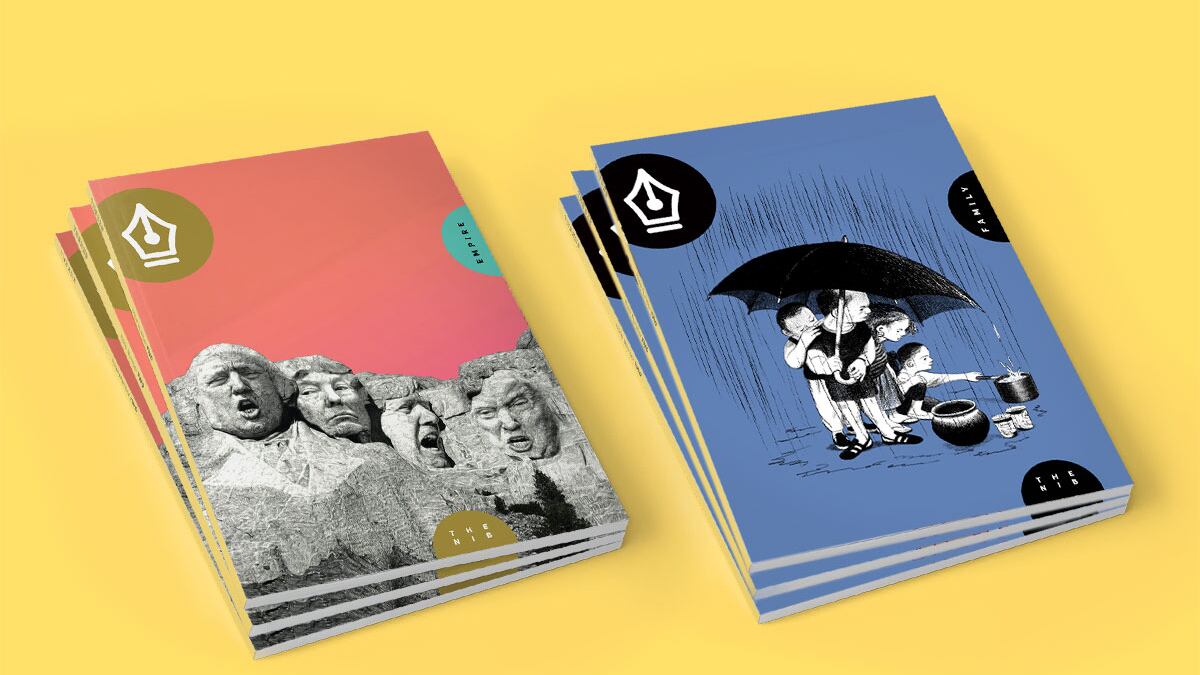

As with the online version of The Nib, the print issues feature nonfiction comics—some historical, some journalistic, some political commentary, all tied to a certain theme. The first issue was "Death" while "Family," as it is wont to do, followed shortly thereafter. The third issue, on "Empire," comes out May 1. Most of the comics fall on the political spectrum somewhere between "liberal" and "hard left."

The move to print isn't entirely unprecedented. Socialist symposium Jacobin quickly launched a physical counterpart to its digital presence shortly after its debut in 2010. But the role that The Nib seeks to play is entirely new: a home for comics journalism, both online and in print. Bors is bewildered by the dearth of comics in new media. "Comics haven't really been brought along for the ride," he says. "None of these sites have hired staff cartoonists."

Though Bors doesn't shy away from the "new media" label, he is conscious of the failed business models of other outlets. After runaway valuations based on ever-increasing Facebook traffic, websites like BuzzFeed and Vice are now facing layoffs. Bors says his goal is long-term sustainability: "I want this thing to actually make money and be sustainable and be a home for this kind of work for decades."

Comics journalism is probably best associated with cartoonist Joe Sacco, who's written and drawn extensively about everything from World War I to the occupation of Palestine. But he does not, by any means, have a monopoly on the genre. The Nib's Empire issue features contributions from more than 30 artists, taking on subjects including the U.S.'s drone war in Somalia, the ascendance of YouTube, crumbling national infrastructure, and Filipino cuisine. All are rendered in vivid, full-color detail.

The journey to print hasn't been a straightforward one. When Bors, a longtime political cartoonist, first started The Nib in 2013, it was part of media site Medium. In 2015, Medium laid off the bulk of its staff. The following year, The Nib relaunched with First Look Media, its current parent company. The launch of the print issues is contemporaneous with the launch of The Nib's membership program, which will fund both the site and the magazine.

Throughout its run, part of The Nib's success has been staying small. Its masthead lists just seven people. But part of it has also been staying in Portland. Though Medium is based in San Francisco and First Look in New York, The Nib is nestled comfortably in the Dumbbell building and, accordingly, pays significantly lower rent than it would in those other cities.

Contributing editor Sarah Mirk says staying in Portland has two other benefits. First, with the ability to draw contributors from all over the world, The Nib avoids some of the myopia that's endemic in media centers. "I think we have a greater awareness of different cultural issues going on across the country," she says.

Second, the company benefits from the presence of Portland's strong comics community. At the beginning of April, Mirk tabled for The Nib at Portland Comic Book Month's 10th anniversary celebration, where City Commissioner Chloe Eudaly invited members of Portland's comics community to hold a convention at City Hall.

After the Empire issue, the next magazine is set to focus on scams. But Bors and Mirk are still committed to getting a diverse array of writers to write and draw about issues other media outlets largely ignore. "Now we're trying to get more people to draw comics about environmentalism and climate change issues," says Mirk, "as well as issues with white supremacy in rural areas."