“He was a retired librarian, seventy-one years of age, and not unhappy.”

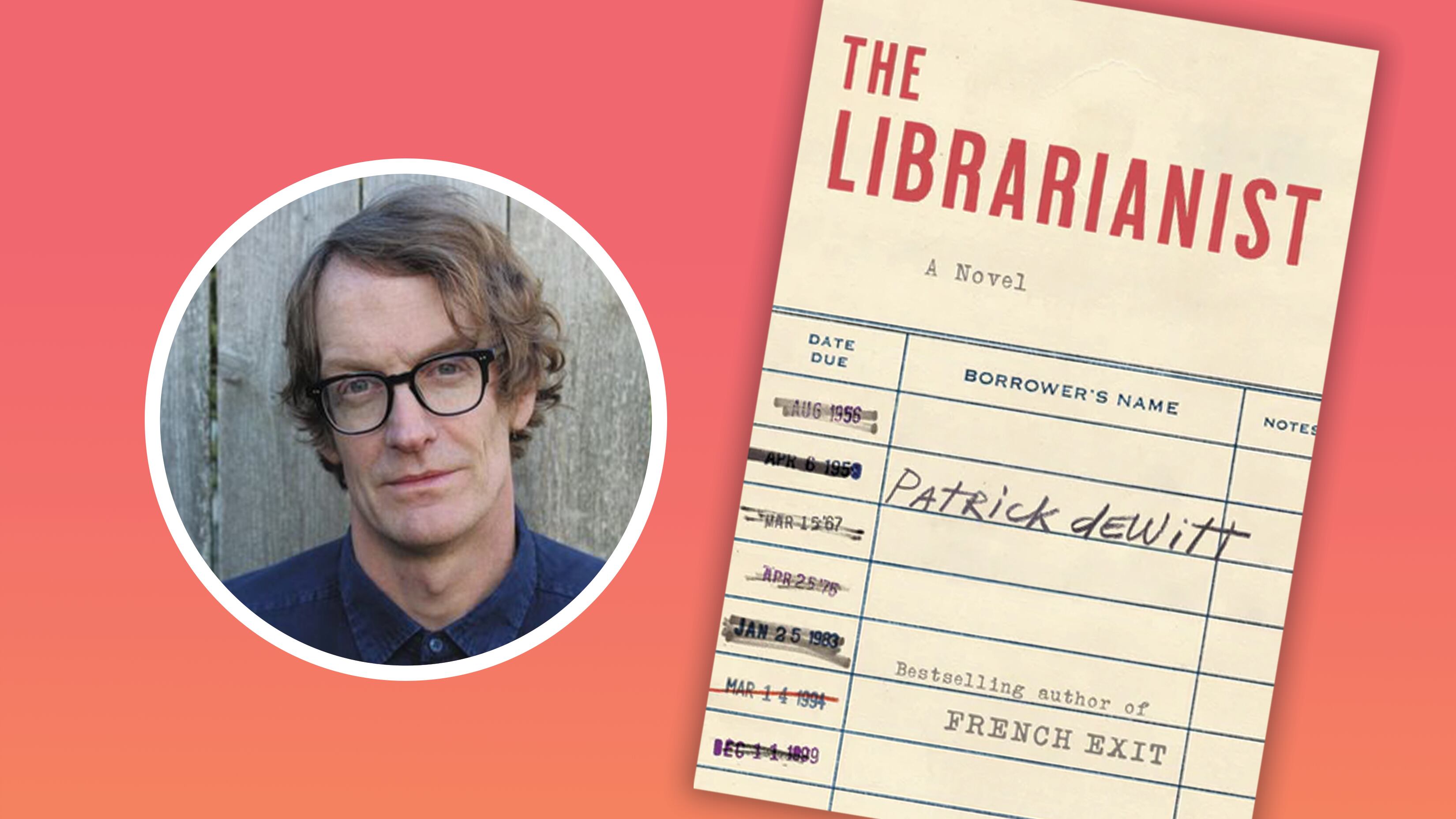

Meet Bob Comet, the principal character in Portland author Patrick deWitt’s new novel, The Librarianist (Ecco Press, 352 pages, $30). The book opens in autumn 2005 when Bob, a reclusive man who has lived in the same mint-colored house in Northeast Portland since childhood, begins volunteering at a senior center. After he discovers the past he and a resident share, the narrative moves back to the years 1942 through 1960, when Bob’s calling as a librarianist began.

That term for the profession was coined by the embittered librarian at Bob’s high school, who counsels the adolescent against “a job whose usefulness has gone away” because “the language-based life of the mind” is a thing of the past. Bob nevertheless persists, “clerking under the dread thumb of Miss Ogilvie” at a branch in Northwest after his graduation from Portland State University. Two library regulars become Bob’s first friends, but the relationships last only a few years, after which begins the solitude that stretches unbroken until his seventh decade.

Then the narrative moves back to a four-day period in 1945 when an 11-year-old Bob runs away from home. He falls in with thespian sisters Ida and June and their dogs, Buddy and Pal, traveling with them to the fictional Oregon Coast town of Mansfield. Bob assists in their rehearsals at the Hotel Elba, an establishment that to Bob appears “handsome but hungry-looking.” On his fourth day away from home, the ends of both Bob’s adventure and World War II coincide. As the sheriff begins to drive Bob back to Portland, the boy feels that “something of the moment had upset his heart,” although he is unable to articulate what that something is. When the narrative returns to 2005-2006, Bob makes a kind of peace with his past and, in the final scene, rediscovers something of the Bob who once took a turn as itinerant thespian assistant 60 years earlier.

DeWitt’s newest novel, like The Sisters Brothers, resembles a picaresque, albeit one in which the main character travels little. It is an episodic work in which characters and places with zany names—Chance and Chicky Bitsch, Les More, the Finer Diner—process past the reader, usually lingering for only a chapter or two. A man wearing a “self-made cape,” a paramedic eating a sandwich while assisting the injured, an elfin elderly man hiding among hothouse plants—these and other outlandish characters are amusing and vivid, but there is a sense that the whole is less than the sum of its parts; that the book’s scenes remain scenes without creating a larger pattern.

In spite of the book’s title and its main character’s bibliophilia, its engagement with other books seems limited. Bob chooses to read Poe’s “The Black Cat” and Gogol’s “The Overcoat” at the senior center, and his recommendation of Crime and Punishment as a young librarian suggests something of his imagination. But those three instances constitute the entirety of The Librarianist’s literary references, a missed opportunity in creating and revealing the character of one whose chief activity in life is reading.

The Librarianist is not without its delights, mostly evocative and original phrases and lines. One of the senior center residents has “unhealthy habits and gargantuan appetites” that have run “unchecked across the length of several decades.” Actresses Ida and June travel with 23 pieces of luggage that are “imposing in scope and confusing to consider.” Fittingly, the passages about Bob reticently hint at unexpressed emotion. Bob’s house is “the location of his life, the place where he passed through time, passed through rooms.” During one of his volunteering visits, he senses “evidence of an odd-shaped fate running through the day.” When Bob finds himself alone and friendless while still a young man, he gains an “understanding of the perilous vastness all around him.”

The Librarianist, despite some weaknesses, offers an entertaining menagerie of strange characters and numerous apt and evocative phrases. And the divergent possibilities in the novel’s ambiguous ending scene give readers two very different stories to ponder after the final word.