While nearly every nonagenarian could sit down and share interesting stories from his or her life, Mitzi Asai Loftus’ tales from her 91 years have an unusual level of national historical significance.

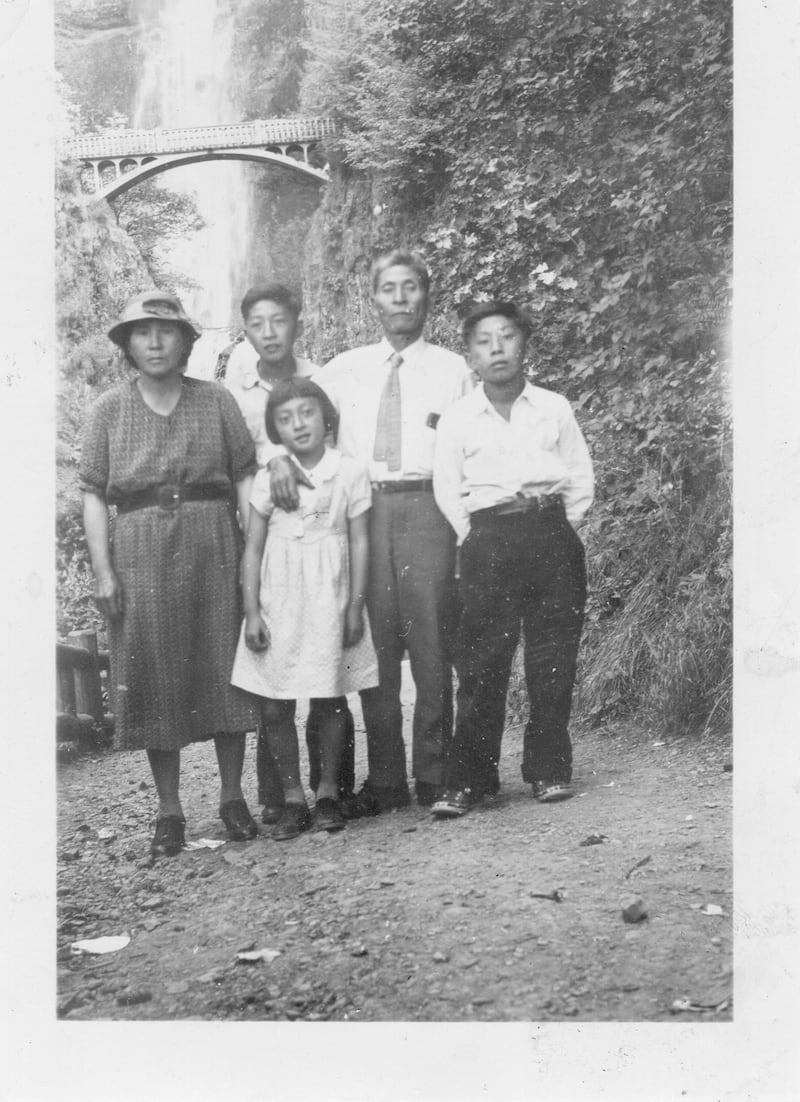

Born on a fruit orchard in Hood River in 1932, Loftus is one of the last remaining Hood River Nisei (second-generation Japanese American) survivors of U.S. incarceration camps during World War II. Her new memoir, From Thorns to Blossoms: A Japanese American Family in War and Peace, was published last month by Oregon State University Press.

Loftus will speak at Powell’s City of Books, 1005 W Burnside St., at 3 pm, this Sunday, March 17, in conversation with her son and co-author David Loftus. She has other book tour stops this spring in Hood River, North Bend, Eugene and Ashland, where she currently lives.

“What I hope people would learn from the story of my life is what I tell almost every audience I speak to,” Mitzi Loftus says. “It is not the prejudice or mean words and acts that hurt me nor any of you, but the good people who see someone do unkind or mean things and do not step forward to say or do something to speak to the situation. See a bully? Speak up.”

The book chronicles her rich and varied life as the youngest of eight children.

In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which sent about 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry (about two-thirds of them U.S. citizens) from their homes to prison camps. Loftus and most of her family spent much of World War II in the camps—Pinedale and Tule Lake in California and Heart Mountain in Wyoming—while two of her older brothers served in the U.S. Army.

She chronicles heartbreaking moments of racism and isolation, such as at school the day after Pearl Harbor: “I was spit upon twice and called “[slur]” and some children refused to play with me at recess. I was hurt and bewildered. At 9 years old, in the fourth grade, I had never known discrimination before this moment. It was only a preview of the treatment I was to receive from grown-ups in Hood River four years later.”

Humiliation and shame from the open racism in post-war Hood River—someone threw a rock through the family’s window, for example—caused a teenaged Loftus to reject her Japanese heritage, including her birth name, Mitsuko. But the book (and her spirit) does not get bogged down. After the camps, Loftus becomes a high school English teacher and college instructor. Later, she earns a Fulbright scholarship to teach in Japan, where she reconnects with her roots.

Her son, David, says his mother is still sharp and active at 91. News reports confirm this, such as when she took up tandem bicycing at age 85 and participated in Providence Bridge Pedal in August 2023. The Oregonian ran a photo of her gleefully waving from the back of a bike at the starting line.

“The most meaningful part of publishing my memoirs is the response of encouragement to do it along the way,” Loftus says. “I have received urgings from not only friends and acquaintances, but people who do not know me, complete strangers who have heard only a small bit.”