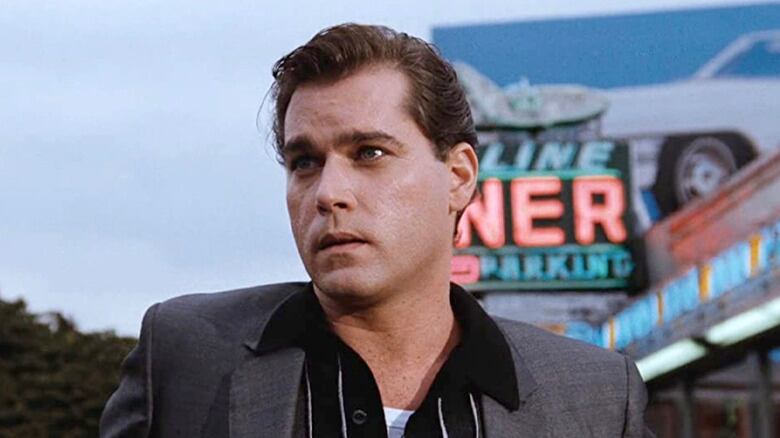

Once Goodfellas’ opening act begins in earnest, we get our first proper introduction to Ray Liotta—starting with his alligator loafers.

From the concrete, the camera ascends, climbing up his silk slacks, knit button-down, perfect chin, cigarette exhale and lazy pompadour. “Objectification” isn’t strong enough a word for the meal director Martin Scorsese’s camera makes of his star.

Liotta’s Henry Hill is an avatar of underworld seduction, drawing us into the mob, but also demonstrating he’s fully bought in himself (gangster glamour is required even to loiter around Idlewild Airport pondering cargo theft). Ever since Henry can remember, Liotta famously narrates, he’s wanted to be a gangster—and when we first see Liotta, he’s arrived.

When Liotta died in his sleep last month at age 67, his introductory image in Goodfellas filled my mind. With all due respect to Liotta’s intense, otherworldly Shoeless Joe Jackson in Field of Dreams (1989) and his unblinking menace in Something Wild (1986), the late actor was never in a movie that meant so much to the world and to him as Goodfellas.

Still, Liotta’s centrality in Scorsese’s fact-based film, which was released in 1990, is curious. One could argue that a dozen different elements have historically drawn more attention than his portrayal of Henry turning from protagonist to antihero to shit heel.

Goodfellas jolted Scorsese’s second directorial act, proved his bankability, and forever linked him to crime epics. It won Joe Pesci an Academy Award, minting him as the unlikeliest movie star of the ‘90s. It garnered Lorraine Bracco an Oscar nod. The Copacabana tracking shot became a cinematic totem. Pesci’s “Funny how?!” bluff is familiar even to those who’ve never seen the film.

But then there’s Liotta, ushering the audience through every detail of wiseguy culture, embodying a scumbag Nick Carraway whose DNA interlaces with the film’s. His cocksure testimony explains why you’d want to be a gangster (“treated like movie stars with muscle”), backed by the intoxicating fusion of his inner monologue and James Kwei and Thelma Schoonmaker’s iconic freeze-frame editing.

Even so, Liotta’s performance is a model of humility. He plays Henry as a willing sidecar to the film’s showier actors—a vessel that the movie fills and then drains of appeal. He’s always the junior half of his relationships, standing in the shadow of men like Pesci’s Tommy DeVito (who kills Billy Batts over an insult) and Paul Sorvino’s Paulie Cicero (who epitomizes fading “Godfather” wisdom, but remains formidable).

Within his marriage to Bracco’s Karen Hill, Henry is at his most human and ghoulish (he’s a philanderer and an addict absent any justification). Despite all the talk of Mafia codes and conduct, their marriage is the story’s true partnership, albeit a perverse one.

In Bracco’s Twitter eulogy for Liotta, she wrote:

“I can be anywhere in the world & people will come up & tell me their favorite movie is Goodfellas. Then they always ask what was the best part of making that movie. My response has always been the same…Ray Liotta.”

It’s worth recalling, too, what Liotta is actually doing in the shot that opens on his loafers. When the lens finally reaches his face, he’s staring into the distance. Henry Hill, it seems, spends his whole life looking, gazing, coveting, visually absorbing the criminal lifestyle.

We witness young Henry’s dilated pupils as he peers from his bedroom window at the mob-run cab stand across the street. In the preceding cold open, Kwei and Schoonmaker freeze on a shot of Liotta slamming the trunk containing Billy Batts’ corpse, then staring into the dark, terrified and doomed. And in the final act, Henry, in a cocaine flop sweat, peers skyward at circling helicopters as though he expects to be smitten from on high.

In the end, of course, Liotta shatters the fourth wall with his stare, indicting those who’ve enjoyed being tourists in mob life as much as Henry has. In the final seconds, Liotta is no longer an object, but the silent voice of every artist involved in the film. Ray’s eyes—narrowed to slits—say it all. And just who the hell are you, watching me?

SEE IT: Goodfellas plays in 35 mm at the Hollywood Theatre, 4122 NE Sandy Blvd, 503-493-1128, hollywoodtheatre.org. 2:30 and 6:30 pm Sunday, June 19. $8-$10.