When the Hollywood Theatre retooled itself in 2015 to screen 70 mm films, The Hateful Eight was among the first titles to occupy the 50-foot screen. Quentin Tarantino’s powder-keg Western ran for five weeks in 70 mm, drawing sold-out crowds and a visit from Tarantino himself.

When the theater eventually switched to screening a digital version of The Hateful Eight, the Hollywood’s projectionists and head programmer Dan Halsted suspected something was wrong. The image looked “sub-par,” Halsted recalls, and they consulted a technician.

The technician’s response? “It looks perfect,” Halsted remembers being told. “You guys have been staring at 70 mm for so long that now digital looks terrible to your eyes.”

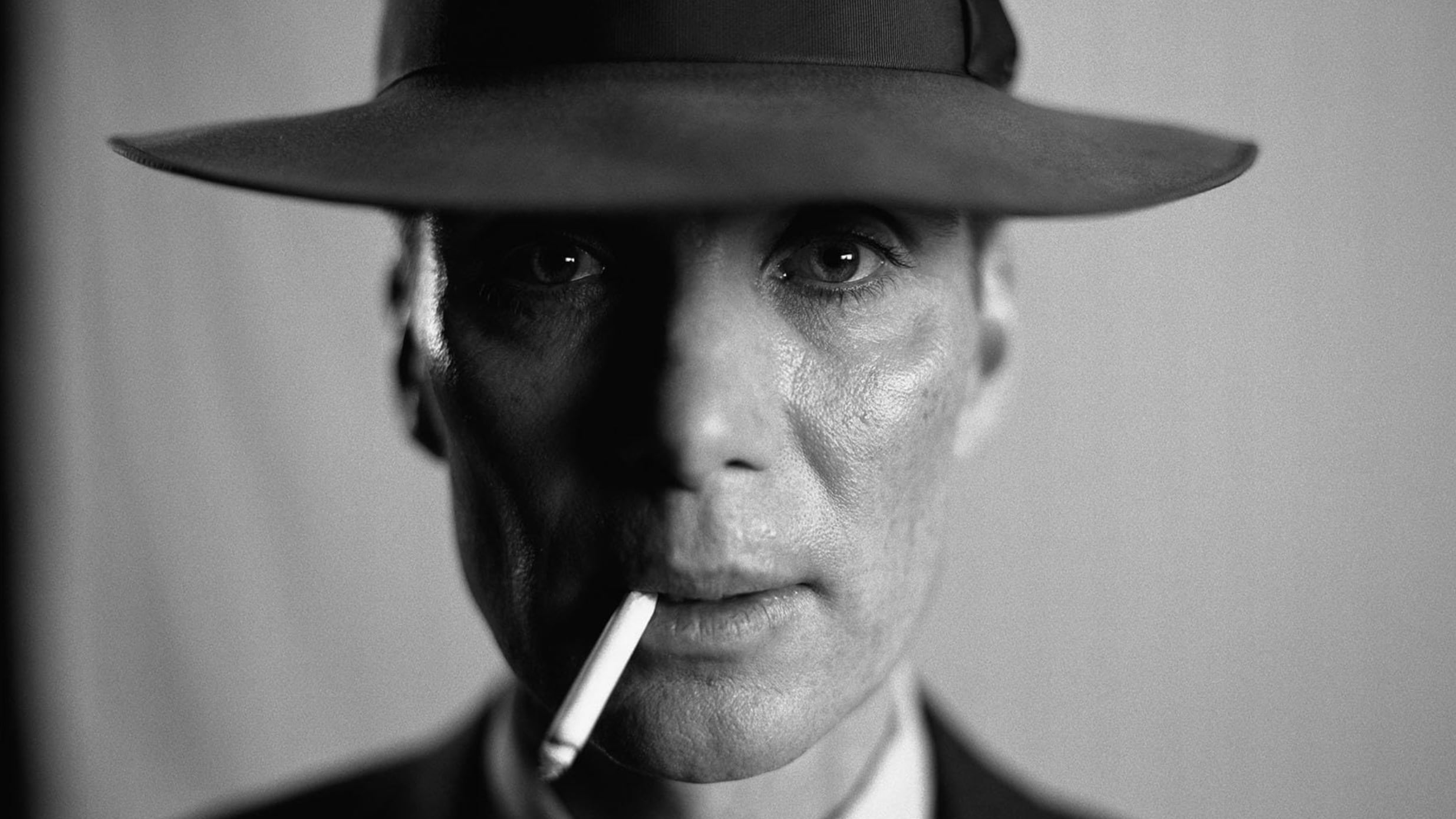

That’s just one of Halsted’s back-pocket anecdotes testifying to the power of 70 mm film, arguably the staple of the Hollywood’s current programming. The theater’s tri-annual 70 mm mini-festivals invariably sell out, Halsted says. And to close the theater’s ninth year of its revitalized 70 mm era, the Hollywood is screening Oppenheimer (2023), Malcolm X (1992), Napoleon (2023), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and The Hateful Eight—all in 70 mm—from Dec. 26 through Jan. 1.

“It is absolutely the best way to watch a movie,” Halsted tells WW. “Digital versus film…everybody always asks about film like it’s a gimmick or whatever. But I watch movies with crowds. I’ve been doing it my whole life. And when a movie is on film, people are more engaged than they are when it’s digital. There’s something about film moving at 24 frames per second that engages the human mind. It’s like people are in a trance.”

No film gauge induces that trance like 70 mm, which revolutionized cinematic image quality in the 1960s for widescreen epics and extravaganzas like Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and West Side Story (1961).

“There’s so much depth in the image,” Halsted says. “It’s the best color grade, especially when [the film is] shot on 70 mm.”

There was a time in the Hollywood Theatre’s history (1963 to 1969) when 70 mm was the only format the Portland movie palace showed. In the 1970s, 35 mm became the cheaper industry standard, but heavyweight titles like The Exorcist and Star Wars still played in 70 mm.

When the Hollywood “went through terrible times” in the 1980s and 1990s, as Halsted puts it, someone simply “walked off” with pieces of the twin Norelco AAII projectors that made 70 mm exhibition possible.

After the theater achieved nonprofit status in 1997 and long-term restoration efforts began, it still took years for the Hollywood to raise the $15,000 in community donations and source the parts necessary to resume 70 mm screenings. When it finally did, the first movie was a fortuitous one: 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Today, 2001: A Space Odyssey is the lone 70 mm print the theater owns and one of its most consistent draws. Any other 70 mm print that plays is borrowed from studios and archives. They may be well worth owning. Halsted says shipping the reels is a financial and logistical ordeal, and a disgruntled FedEx driver isn’t uncommon. (Malcolm X, for example, is 10 reels, 40 pounds each.)

In 2022, to alleviate the pressure on the Hollywood’s only two 70 mm projectors, the “Film Forever” campaign raised the funds to buy two backup Norelco AAII projectors, purchased from the collection of Frank Sinatra’s private projectionist. The 1,600-pound mammoths are highly sought after, and Halsted remembers Get Out director Jordan Peele buying a couple projectors at the same sale.

As for these year-end screenings, 2001, Oppenheimer and The Hateful Eight are all repeat attractions at the Hollywood. Ridley Scott’s Napoleon is an interesting case, however, as it was shot on digital and later printed on 70 mm.

In Halsted’s eyes, movies that aren’t native to the 70 mm format don’t look so different from digital when transferred (though the sound might be slightly better, he says). Even so, Napoleon’s transfer to 70 mm just a month after its wide release could suggest that studios are noticing how theaters like the Hollywood draw cinephiles for anything in 70 (even from as far away as Japan, in Halsted’s experience).

“Seventy isn’t going away,” Halsted says. Despite there being only one lab in the world (FotoKem in Burbank) that strikes such prints, vocal advocacy from directors like Christopher Nolan and Quentin Tarantino is keeping a 70-year-old mode of film exhibition front of mind and a workable business for some movie studios.

“All other media is made for personal consumption,” Halsted says. “Film is made for a communal audience experience. That’s what sets it apart. I can’t stand it when I find collectors or archives that don’t loan out prints. You might as well throw it in the garbage. It only exists to show it to a crowd.”

By that logic, every time 2001 comes out of its secret storage place at the Hollywood or Malcolm X is hauled reel by reel from a delivery truck to a projection booth, the films get the life they deserve.

SEE IT: 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Hateful Eight, Malcolm X, Napoleon and Oppenheimer screen at the Hollywood Theatre, 4122 NE Sandy Blvd., 503-493-1128, hollywoodtheatre.org. Multiple showtimes, Dec. 26-Jan. 1. $11-$15.