Since its premiere in 1952, Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (that’s GOD-oh, not guh-DOH) has captivated theatergoers of all stripes. The absurdist masterpiece pulls off the impossible, transfixing viewers on a story where not only do we see nothing of any import happen, but the two-act structure means we see that nothing twice. The intervening decades have seen works of art made inspired by or in response to Godot—novels, comic strips, web series, video games and, yes, more plays.

Corrib Theatre will stage some of these latter-day works in its forthcoming season at CoHo Theatre, and has chosen to kick off their almost yearlong exploration where it all started: with two tramps on a mission that they may never complete. As Waiting for Godot enters its closing weekend Dec. 12–15, audiences shouldn’t wait on getting tickets.

Said tramps are Vladimir “Didi” (Roo Welsh) and Estragon “Gogo” (Karl Hanover), lifelong friends set to meet Mr. Godot at a prearranged roadside spot. But who is Godot? Why are they meeting? What’s been delaying him for so long? The answers to these questions and others will never be revealed, as we instead focus on Didi and Gogo’s attempts to pass the time, musing on their stations, their grievances, and the mysteries of life itself.

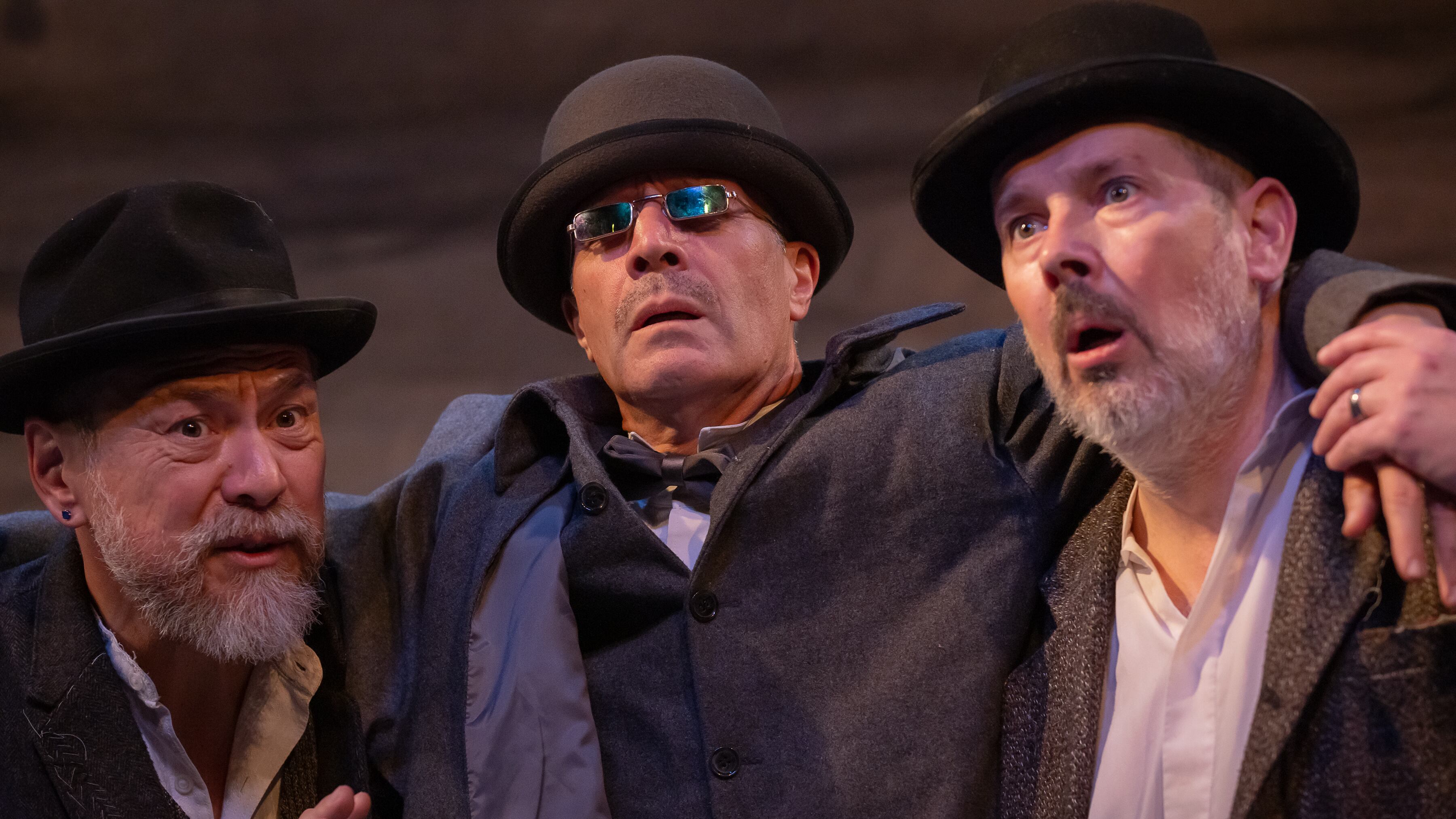

Although not explicitly stated in the text, Beckett infused Godot with his love for vaudeville comedy and silent movies, influences that director Patty Gallagher and the cast lean into wholeheartedly. Although Welsh was not quite off-book during the Friday, Dec. 6, performance, he and Hanover shine as a fast-talking double-act reminiscent of Abbott and Costello. This extends to the travelers our heroes meet during their interminable waiting: the wealthy buffoon Pozzo (Jonathan Cullen), who plays like a mashup of Margaret Dumont and Curly Howard, and his mute slave Lucky (Doren Elias), who exhibits the wide-eyed melancholy that Buster Keaton honed to perfection.

Fortunately, the production also remembers the tragic element of this “tragicomedy in two acts,” and that begins with Kyra Sanford’s set design. As always, the only landmarks for Godot’s meeting point are a dead willow tree and a boulder beside a barren country road. However, closer inspection reveals these natural features are made of old junk welded together and spray-painted silver and grey to match the story’s desolate backdrop. While Beckett’s text was likely informed by his experiences in Nazi-occupied France and the post-war devastation, Gallagher’s production feels almost post-apocalyptic, as if Vladimir and Estragon are entirely removed from reality and have been abandoned in some purgatory with no real company but each other.

That core relationship proves to be why Godot’s influence has endured these past seven decades. Vladimir and Estragon are so utterly alone in their blighted landscape that their only choice is to lean on each other—for Didi to comfort Gogo’s weary aches, and for Gogo to allay Didi’s worried mind. The theme of needing human connection amid the bleakest of circumstances is a universal one, but it’s especially poignant in our post-pandemic digital age, when knowledge of the world’s faults and powerlessness to do anything about it go hand in hand. Just like Vladimir and Estragon, we have to learn to help each other in trying times, because sometimes that’s all we can do.

Starting in February 2025, Corrib Theatre will examine Waiting for Godot’s successors with Pass Over, a contemporary American spin on the text with a focus on Black male friendship, and Godot Is a Woman, a spring festival of short plays from female and nonbinary perspectives. Beckett himself objected to women staging Waiting for Godot, a stance his estate still enforces. Before then, it’s worth it to see where it all started and how two sad clowns by the side of the road can make us laugh, cry and, on occasion, even think.

SEE IT: Waiting for Godot at CoHo Theatre, 2257 NW Raleigh St., 971-202-6567, corribtheatre.org. 7:30 pm Thursday–Saturday, 2 pm Sunday, Dec. 12–15. $15–$40.