Any gallery should be thrilled by the chance to arrange the first proper showcase of a legendary masterpiece long thought lost—and thereby reawaken interest in unfairly forgotten visionary Harley Gaber.

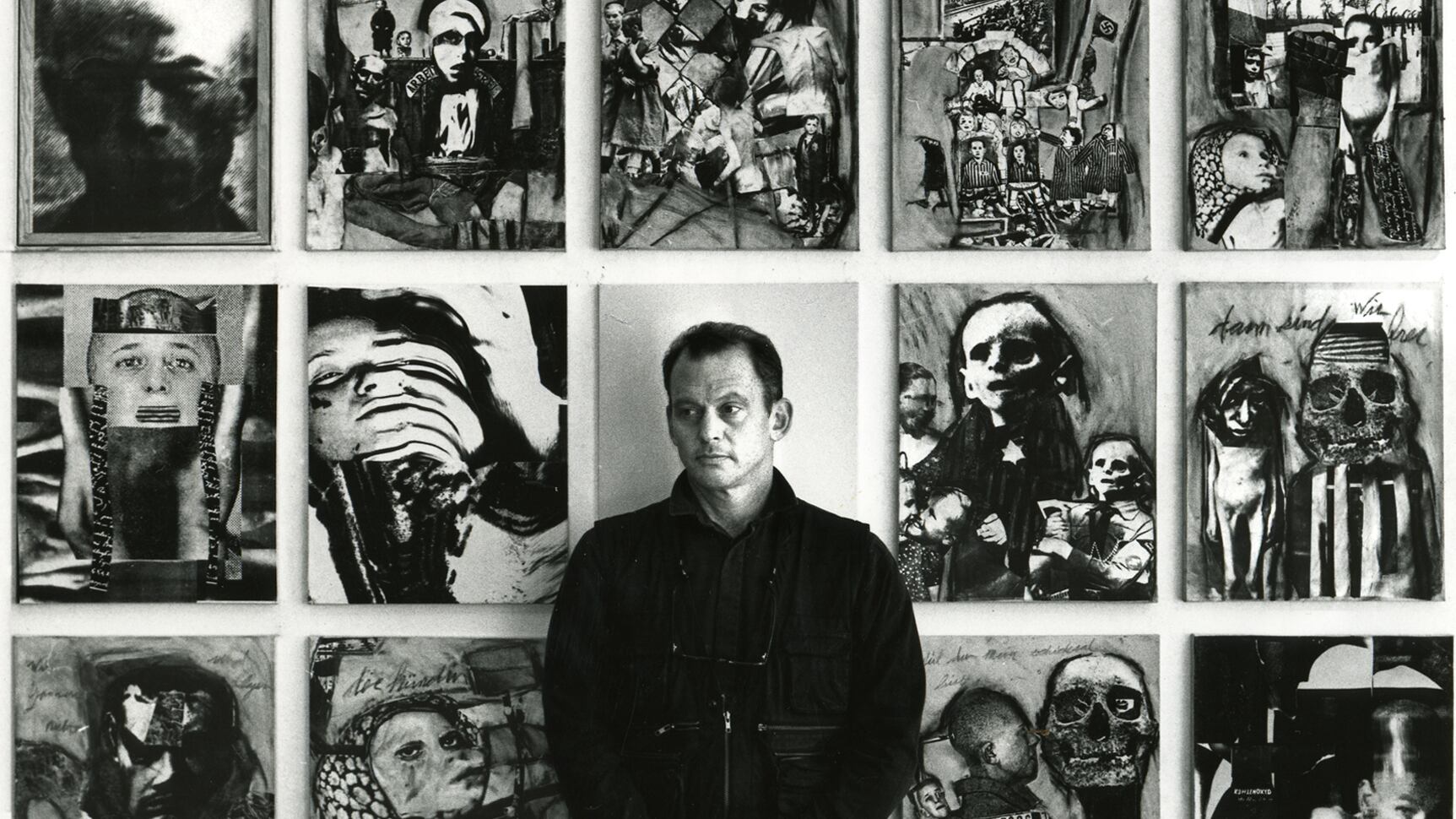

Gaber, a classically trained composer considered among the leading lights of American minimalism, was also a gifted visual artist whose photomontage and mixed-media projects won international acclaim in the 1970s and ‘80s. In 1993, he began assembling a vast store of photos obliquely chronicling Germany from the Weimar Republic through the end of World War II for Die Plage, a magnum opus that would consume his next nine years and fill a hangar on the Oregon Coast.

Eventually numbering some 4,200 separate panels of collage arranged in chronological order, Die Plage (which archivists estimate forms a 12-foot wall of imagery five canvases high running 1,680 feet in length) has never been shown in full.

Now part of the surviving Plage trove is being showcased in the gallery area of the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education. It’s a must-see for anyone who wants to experience Gaber, who took his own life in 2011 after completing a musical composition (“In Memoriam”) commissioned by Dan Epstein to honor his late mother.

As the exhibit enters the second of four months on display in the museum’s Old Pearl premises, WW sat down with the center’s executive director, Judy Margles, to discuss how little we truly know about Die Plage (“The Plague” in German) and how it darkly reflects horrors past and present.

WW: How much of Die Plage do you use?

Judy Margles: We have four collages in our teeny tiny gallery, or 390 images out of around 4,200. When installed, each one is five canvases high and 16 in length—80 in all—and feels about 12 feet high and 32 feet long.

And there’s some of Gaber’s music as well?

The curator decided “In Memoriam,” the work honoring Epstein’s mother, should play inside the museum so people could listen while at the exhibition. Another piece called The Winds Rise in the North can be heard outside. We’ll also be presenting a concert Jan. 22 that features Gaber’s music as well.

Why pick these collages?

They’re coherent in concept as well as compositionally coherent. [Gaber] was systematic and very, very deliberate. He wanted the images to be seen in the context of another over and never hang alone. And he intended them to be chronological, which, of course, in our space, they’re not. The murals we’re showing are all from the Holocaust. There aren’t any from the Weimar ‘20s.

Because that didn’t fit lesson plans?

From our choices, we want to pull out the themes that interest us as we’re talking to visitors—schoolchildren, particularly. Teaching the Holocaust works best when you can open minds with ideas relevant today. Connections not comparisons. That is the way we teach. And then we’ll say something about injustice persisting in an interconnected world. How might knowing about the Holocaust contribute to our understanding of our responsibilities to one another?

Looking at Harley’s work provides us with such a brilliant opportunity to think about issues relevant then and still today—media literacy, propaganda, coming of age in the time of crisis. Think about what the children have been through during the pandemic, which is a plague!

We’re all dealing with the rising tensions between loyalty to one’s country and extreme nationalism. In the museum, we teach about democracy and pluralism, which function when everybody works together in a diverse society based upon cooperation. That’s what’s evidenced by these canvases. If we do not cooperate, if we do not work together, Die Plage tells us viscerally the collision of history will ensue.

Did Gaber ever publicly talk about what he wanted from people’s reactions to his art?

You approach Harley not ever knowing exactly what he was thinking, but…he did start destroying his work. On the canvases are photographic images stretched for collage, and he started razor cutting the images out of the frames.

Why assume he was destroying the images, though? Did he ever announce a stopping point? Was he the sort to keep tinkering? Was there a unified vision?

I believe he had a vision and really knew what he wanted to do. It was all so neat. You’ll see some of the razored-out images at the exhibition, and they’re very tidy. It wasn’t like he was slashing away at them maniacally. He very deliberately cut them out of the frames so they’d exist in the body of work. And he’s gone. We don’t know exactly his reasons for anything…

You know, he never saw himself as a documentarian. Traveling to Germany all through the ‘90s, he never imagined that he was providing a record of the Weimar era. His interest was studying what happens to human beings caught up in the sweep of history. He really sought to individualize, and you see that in the images. Throughout these monumental collages, there are perpetrators and there are victims.

SEE IT: Die Plage is on view at the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education, 724 NW Davis St., 503-226-3600, ojmche.org. 11 am-4 pm Wednesday-Sunday, through Jan. 29. $5-$8; members and children under 12 free.