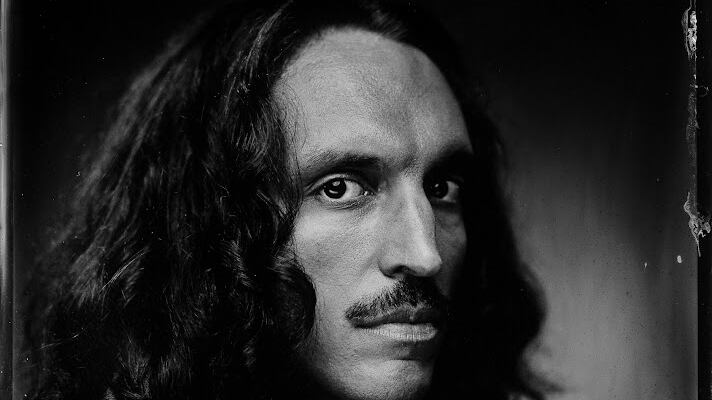

Welcoming Jim Hair into his studio, tintype photographer Noyel Gallimore is giddy. Hair, a consistent force in the Portland photography scene since the ′70s, is a professional in every sense of the word. Feeling like a child in the eyes of one of his key influences, Gallimore talks with Hair about their shared craft and eventually takes his idol’s picture. After the lens is exposed on his 100-year-old camera, Hair looks at the portrait. “Wow, now I have a photo for my funeral,” he says.

Gallimore is one of the few photographers in Portland who takes tintype photographs, a form of photography that first came to prevalence in the 1850s. While creating tintype photographs does take patience, the resulting photos are full of detail and often last longer than the subject of the photo.

Growing up, Gallimore’s father exposed him to photography. Always taking photos that filled binders of photo albums and recording everyday life on his video camera, Gallimore’s father used photography and videography as a means of documentation. During his teen years, Gallimore found himself doing much of the same. Only once he got older did he start using photography as a way to express creativity and as a means of connection with others.

“As I got older, I [realized] the significance in a photo of a person,” Gallimore says. “Humans are really sentimental, and we love the people in our lives. Being able to remember those people, especially after they’re gone or far away, is an invaluable asset.”

Tintype photographs are achieved through a process called wet plate collodion, a process that requires patience, a virtue that courses through every vein of Gallimore’s process. First, Gallimore cuts a piece of aluminum to the correct size. After coating the plate in a mixture of collodion, ether, alcohol and metal salts, the plate is submerged in silver nitrate. This silver nitrate reacts with the metal salts and creates photosensitive silver halites, meaning the resulting photo literally ends up being made of silver. This process takes 10 minutes and is required for every one of Gallimore’s photos, but it leads to undeniably unique results. Many tend to have strong reactions to the final product, whether it be seasoned professional photographers or a customer who saw a flier for his studio at a bookstore.

“A lot of people will cry, and a lot of people will be overjoyed, speechless,” Gallimore says. “I think a lot of that emotion comes from the process [of] putting so much care and effort and intention into what we created.”

Much of that care and effort comes long before his customers are put in front of the camera. Gallimore likes to take his time with his subjects and grow to understand them before taking their portrait. “When I have someone over to the studio, I always take 30 to 60 minutes just getting to know them,” he says. “Asking them why they want a photograph, what their intentions are with getting a portrait made, and why that’s important to them. That helps me get a better grasp of not only what they value in the process but what they value in themselves and in their life.”

Originally hailing from Memphis, Tenn., Gallimore ended up in Portland purely because the opportunity was offered to him. He needed somewhere to live, and a friend offered him a spare room. After putting all his things in a truck and driving 3,000 miles, Gallimore made Portland his home. “I love connecting with local artists, businesses and just people who are fascinating,” Gallimore says. There are all kinds of people in Portland. It’s just a weird melting pot, a strange place.”

When not in the studio, Gallimore can be found at markets around Portland and beyond, taking portraits of anyone who may find themselves interested. While it does make for great exposure, pop-ups have proven to be very different from the studio. Most portraits are done in 10 minutes as opposed to two hours, leaving Gallimore to lament the lack of connection.

“I can make beautiful portraits at a pop-up. It is possible. I just think, personally, that the meaningfulness of that image is lacking because there wasn’t as much time and energy put into creating attention for the photo. It’s more like getting in a photo booth at a bar.”

Gallimore represents a rare breed of a retro photographer, one that doesn’t just take photos in an antiquated medium for the aesthetic of it. “Old-timey” photos can be made by anyone with a phone and a Photoshop subscription, but Gallimore uses the tintype medium as a way to capture a side of someone the subject themselves may have never seen before.

SEE IT: Noyel Gallimore at The Oddities and Curiosities Expo, Oregon Convention Center, 777 NE Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd., odditiesandcuriositiesexpo.com. Oct. 5-6.

Noyel Gallimore Tintype Studio, 3640 SE Lexington St., noyelgallimore.com. $80–$180.