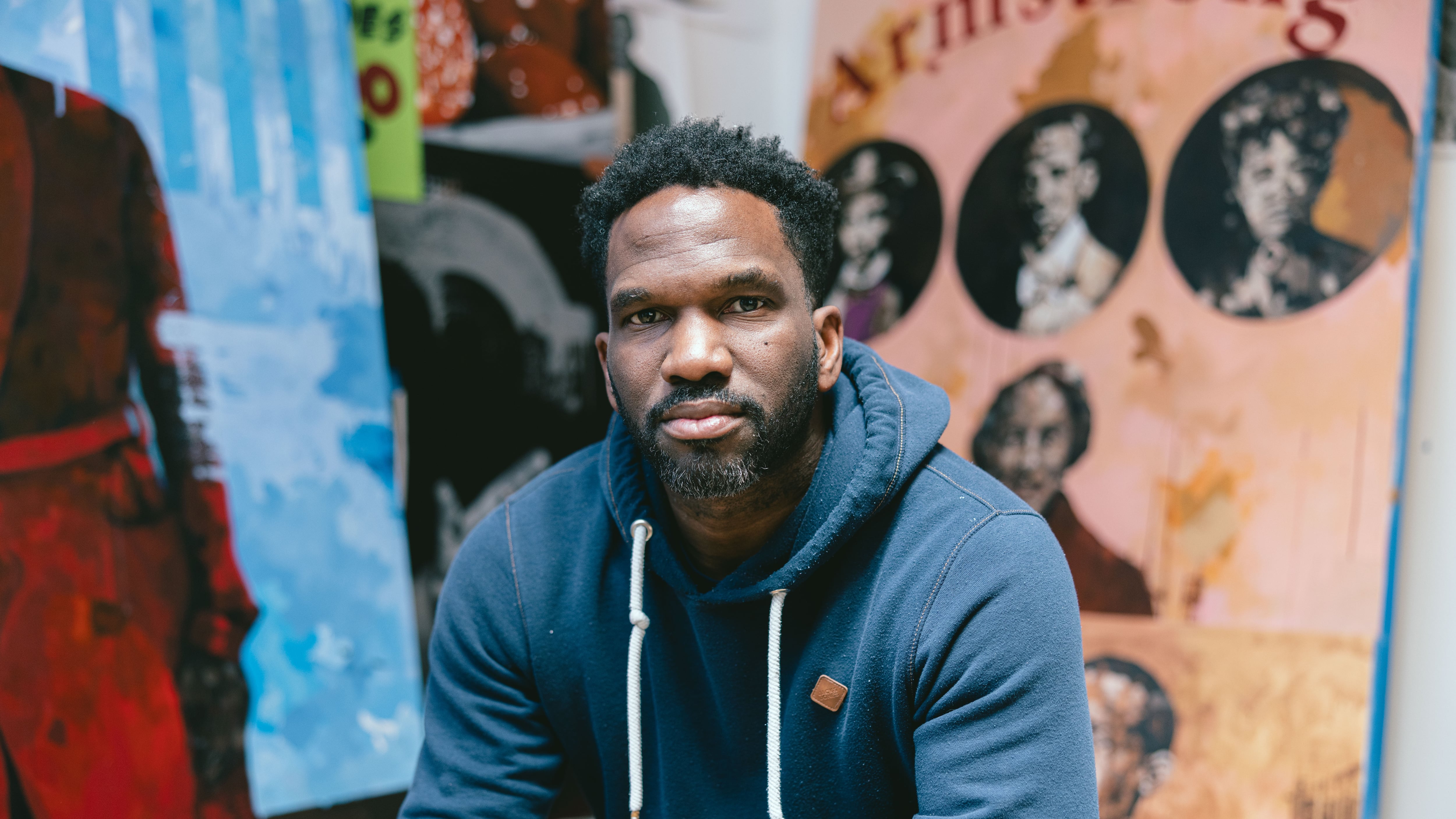

Viewers should lose themselves in Jeremy Okai Davis’ latest portrait exhibit, from the stage, a calling…, which opens Thursday, Nov. 7 at Elizabeth Leach Gallery, as soon as possible.

For his third art installment since he began working with the gallery in 2019, Davis looks to highlight the history and spirit of Black performance through a collection of portraits analyzing and celebrating the rich, complex and often tragic development of African American arts as acts of resistance and resilience.

For Davis, a Portland resident since 2007, the dynamic and often outlandish cultural critiques of Richard Pryor and Dick Gregory provided clear examples of comedy creating jovial—if not contentious—spaces to explore inequality, cultural faux pas, and racial tensions. That clever dedication to honest self-expression despite the risks and threats of being understood has always been remarkably appealing, and it’s that very duality that drives this exhibit.

“I started with this idea of stage comedy,” the Charlotte, N.C., native recalls. “Laugh to keep from crying…Black people often have to do that.”

Davis’ research on each artist and their circumstances informed his portraits visually, and soon he was beyond comedy, finding that same inspiring duality across genres in African American stage acting and music, particularly during the vaudeville era, which overlapped neatly with Jim Crow. With his impressionist portrait style that lends to historical significance, Davis put paint to canvas, memorializing people and places previously new to him.

Davis hasn’t always painted with this sort of cultural depth. About a decade ago at the Studio Museum of Harlem’s Speaking of People exhibit, he found himself presenting his cleverly pixelated work alongside that of legendary artists such as Kerry James Marshall and Theaster Gates, and felt inspired, “called” even, to speak more with his art.

Davis’ latest exhibit seems to be a culmination of that calling, showcasing his ability to tell the most inspiring stories through fine art.

During a recent reading of Hanif Abdurraqib’s A Little Devil in America: In Praise of Black Performance, Davis learned about Ellen Armstrong, born 1914, a little-known Black magician who started apprenticing at the tender age of 6 with her father, the famous J.H. Armstrong, and his traveling show. In 1939, when the elder Armstrong died, Ellen kept the show going for another 30 years with the help of her stepmother, finally retiring in 1970. Davis was in awe and felt he had to create a piece about her. “This is like…Black Girl Magic, you know?” he asks, before admitting, “I have to say, she inspired me.”

In his focal piece, Cake Walk (Bert + George), 2024, Davis toys with abstract brushstrokes in muted pastels, stenciling the words “CAKE WALK” in a bold font and curious coloration seemingly at odds with the tempered backdrop. Below the words, two circles contain portraits in Davis’ signature style—a distorted effect reminiscent of looking through a droplet-splashed window—portraying sharply dressed bow-tied Black men with less than jovial, or perhaps even sad, expressions.

A “cakewalk” now means an easy task, “a piece of cake.” But before the Civil War, the term described a dance that slaves routinely used to covertly parody how slave masters moved. When slave masters saw the dancing, they were intrigued, holding dance contests for their slaves to win a chance at cake. By the late 1800s, the dance was a key part of minstrel shows, often performed by white people in blackface. Bert Williams and George Walker were Black men who performed in blackface, billing themselves as “Two Real Coons” in order to draw moneyed white crowds. Away from the bright lights of the stage, they had little reason to smile.

Dripping with lustrous details that quickly tease out audience curiosity, each article of Davis’ artwork tells the essence of a story, inviting viewers to seek further details and get lost in a beautiful history encompassing Black American existence that may have otherwise gone untold.

“I see this as a sort of short form,” he says. “Like CliffsNotes of African Americans in performance.”

SEE IT: from the stage, a calling… by Jeremy Okai Davis at Elizabeth Leach Gallery, 417 NW 9th Ave., 503-224-0521, elizabethleach.com. Opening reception 5:30–7:30 pm Thursday, Nov. 7. 10:30 am–5:30 pm Tuesday–Saturday, Nov. 7–Dec. 7.