Quick: Open the website of any pot shop in Portland.

Almost certainly, there's something blue on the menu—Blue Dream, Blue Cheese, Berry Bomb, Blue Headband, Blue Diamond Phillips.

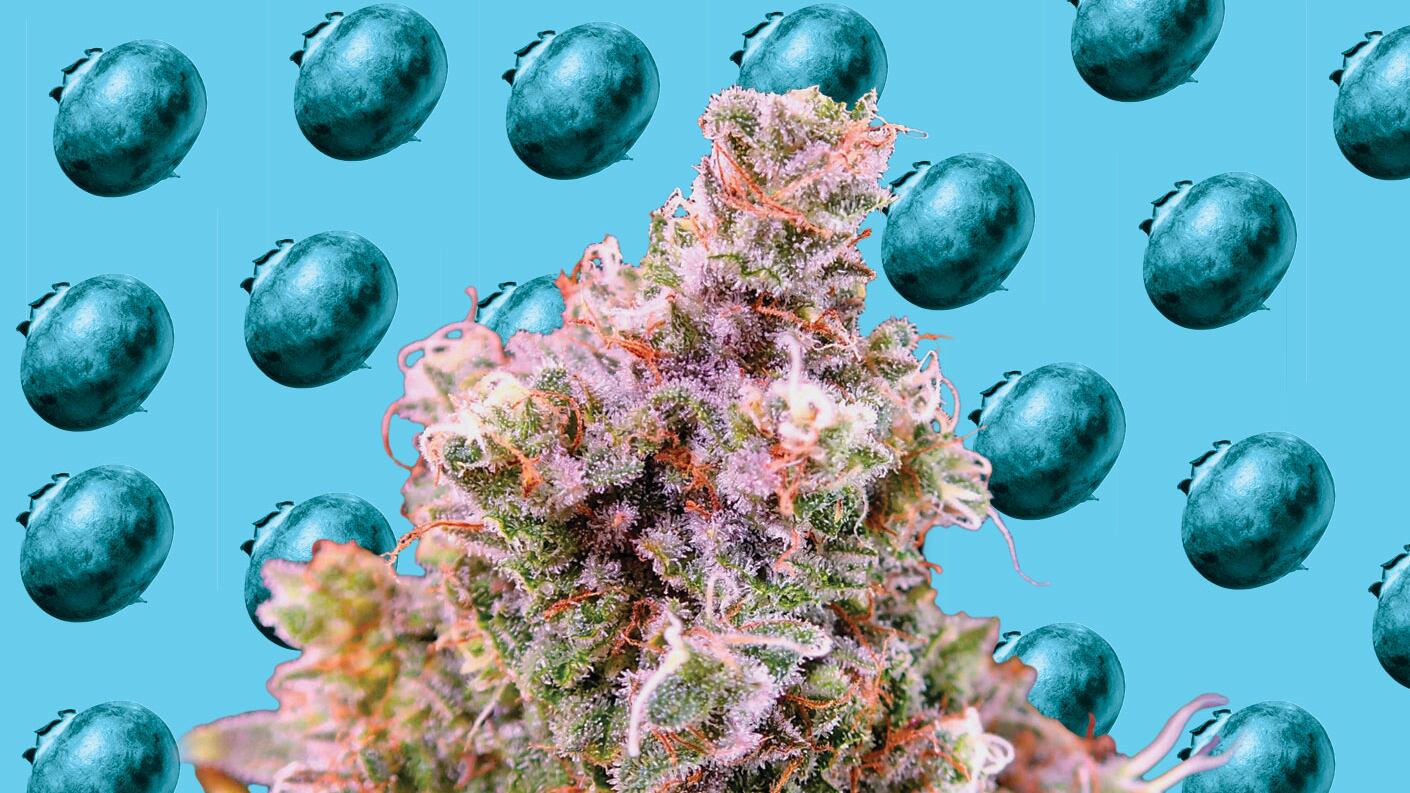

According to cannabis lore, the taproot of all those strains can be found in Eugene. You've probably seen it, too: Blueberry, arguably the most widely seen genetics of its generation.

The legendary Blueberry was bred by a man named DJ Short, who runs Old World Genetics, which is now based outside Los Angeles. His son, JD Short, is still in Eugene, recently launching a breeding company called Second Generation Genetics.

Maybe you've heard stories about a seed hunter finding Blueberry in the mountains outside Chiang Mai, or a soldier bringing it back from 'Nam.

The actual truth is less exciting, says JD Short.

"It's Thai, Chocolate Thai, Afghan and Oaxacan," he says. "Those were the four strains DJ started with. All his strains started with those genetics."

Why are Blueberry and its many offspring so wildly different from other strains? That has to do with a tiny twist on the basics. More on that in a minute.

Traditional cannabis breeding involves pollinating a female plant with a male. Because the males don't produce flowers of their own, it's hard to know exactly what traits they have unless you pollinate many female plants and observe the commonalities in the offspring. DJ Short did that, keeping rigorous notes about each phenotype that emerged and his efforts to stabilize the genetics into a consistent set of characteristics—a strain.

"Blueberry's been around since, I don't know, 1980?" JD Short says. "The Blueberry pheno that everybody loves and raves about now showed up in DJ's work probably around 1979."

Blueberry stood out from the start. The color and aroma that emerged from that plant were unlike anything American cannabis users had ever seen.

"When it first came out, what set his stuff aside was that he had stabilized the color purple, with berry and fruit," JD says. "A lot of the herb that was around at that point was spice weed, or it was the Afghan, which was skunk. DJ came along with these things that were berry and purple, and it just blew people's minds."

The starter seeds weren't necessarily exceptionally rare, JD says. He figures they may have come through the American government, as is common lore in the trillion-dollar U.S. pharmacopeia industry.

So why didn't another berry bloom for another breeder?

While the complex genetics of the cannabis plant mean there are always oddities, you'd think that such strong berry notes would have shown themselves elsewhere if they were common enough to be stabilized.

Therein lies the big secret of Blueberry.

In the late '70s, breeders were just starting to experiment with indicas. To create Blueberry, DJ Short used female sativas, pollinating them with male indicas. He was swimming against the stream.

"When the Afghan came around, what everybody was doing was using the female Afghans, because they were indicas, they were novel and they produced well, they finished quick, they were short and they were potent," JD Short says. "DJ didn't like the Afghans—he didn't like the smoke. All his strains are about the end product. He preferred the sativas as his mother, so he used his male Afghan on his sativas, which was the opposite of what everyone else was doing."

The results of his little twist? Blueberry.

"The reason it's in everything is, they're some of the most reliable true-breeding strains on the market," JD says. "You get your pack of seeds and you get your male, you throw it on your favorite female, and you have stabilized strains."

But are all those blue and berry strains really descended from Blueberry? As far as JD is concerned, they are.

"To be honest with you, my nose hasn't come along with anything yet," he says. "There's a certain smell in there—a floral-berry-earthen-hash smell in there—that's unique. I've been smelling it literally since I was in diapers, so it's hard for me to miss."

How could a little strain from Eugene spread its genetics across the world? JD has a theory on that, too. Call it the lore of the tour.

"Back then, Eugene was known as the stopover town," he says. "There was a really good music scene that happened in this town. It was a pretty happening place for musicians who wanted to play in Portland and then maybe scoot down to Eugene and have a little retreat. It was known as the cool retreat place. The cool rich kids kinda wanted to come here and hang out. They would come here and get genetics, and they would take them back to Northern California. Once those genetics made it to Northern California, it was quickly established. And it changed the industry at that point."