Out of context, a list of the items on display at the International Outbreak Museum (outbreakmuseum.com) reads like the haul from a failed dumpster-diving mission, or the inventory at a hoarder’s estate sale.

A jar of rancid milk. A bag of 24-year-old deer jerky. A diaper-changing station from an auto dealership in Hillsboro. A Trader Joe’s shopping bag whose contents once sickened an entire soccer team.

It’s a germophobe’s house of horrors, and hardly seems a place the general public would want to visit—a fact even the curators acknowledge.

“Depending on how you look at it, this is trash,” says Hillary Booth, lead epidemiologist for the Oregon Health Authority’s Public Health Division.

But for Dr. Bill Keene, this small office on the seventh floor of the Portland State Office Building, where he worked for 20 years, was essentially his trophy room.

A legend in his field, the thickly bearded epidemiologist spent his career investigating outbreaks of infectious disease. He’d keep souvenirs from each case, to serve both as educational tools and as monuments to his team’s successes. As his notoriety grew, other health departments began sending him artifacts from their own investigations.

When he succumbed to pancreatic cancer in 2013, at age 56, Keene had unrealized ambitions to turn the collection into a tourable museum. Two years after his death, his co-workers did it for him.

And while the exhibits lining the cabinets might look like garbage, each piece tells a story—nauseating, sometimes gag-inducing stories.

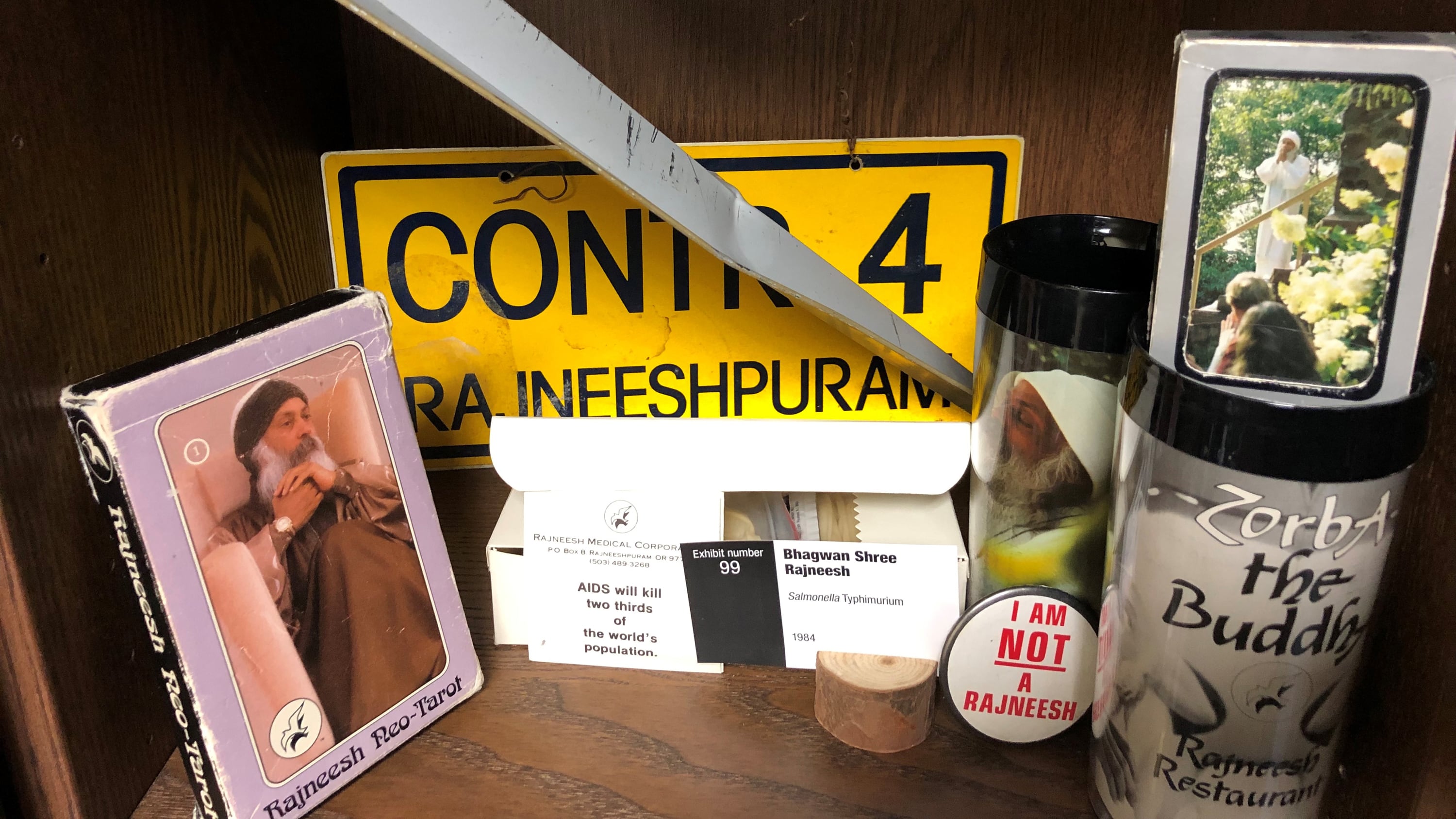

Around 160 items are on display, from a box of tampons at the center of a famous case of toxic shock syndrome in the late ’70s to a deck of playing cards that contributed to a norovirus outbreak at a bridge tournament in Tennessee. In most cases, the packaging is authentic while the contents are simulated—the papier-mâché cantaloupes hanging from the ceiling were created by Keene himself. Naturally, a whole shelf is dedicated to the Rajneeshees and the act of biological terrorism they perpetrated against fast-food restaurants in The Dalles, including a piece of siding from their former compound.

For public health officials, the museum is both a historical resource and a tribute to their work. But it’s as much a tribute to Keene himself.

“He was a powerhouse,” says Booth, who worked alongside Keene for six years. “Whenever he’d talk about things he did, he’d mention the museum. Slowly, epidemiologists, food safety people and laboratorians would just get really interested, like, ‘Wow, that outbreak is so cool, and I can go look at the packaging!’”