Pride isn't canceled. Only the parades are.

Going into June, the time typically reserved for a celebration of LGBTQ+ history and community, it appeared that the month's usual events—the drag shows, the dance parties—would all be postponed, or at least moved online. But what we've seen happening in cities across the United States the past three weeks reflects the roots of the season more than the floats and rainbow-festooned merchandise.

After all, Pride began with an uprising.

On June 28, 1969, in New York, two transgender women of color, Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, fought back against police harassment, sparking a week of rioting that ignited the modern gay rights movement.

In the decades since, the month evolved into more of a party than a protest. To be sure, there have been many advances to celebrate, including this week's landmark Supreme Court decision protecting LGBTQ people from discrimination in employment.

Eventually, though, corporations glommed on, attempting to profit from the movement and diluting its radical origins. But in 2020, with anger over the police killings of African Americans pushing millions of citizens into the streets, that spirit of revolution is back—particularly for black members of the LGBTQ community.

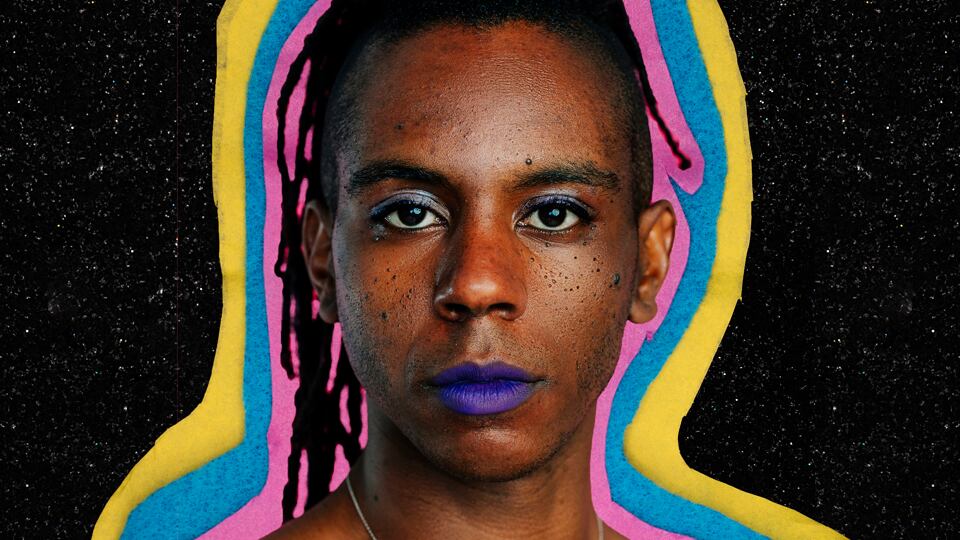

That's why, this year, we reached out to seven queer black Portlanders—from artists to activists to a local civil rights pioneer—and asked them a simple question: What does Pride mean to you?

Photos of Cameron Whitten and Salomé Chimuku, Leila Haile and Jayy Dodd by Gia Goodrich.

Cameron Whitten and Salomé Chimuku, Co-founders of the Black Resilience Fund

The Pride of the present is a far cry from its origins.

In the '70s, Pride emerged as an opportunity for LGBTQ+ people to resist the status quo. To celebrate every part of who we were. To fight for our lives.

And unlike today, there was no space for police at Pride, because the police were complicit in the violence against our communities.

We're seriously concerned about the pinkwashing of Pride celebrations around the world, where companies and public agencies spend millions to appear LGBTQ2S+-friendly, but then go missing in action when other marginalized communities are under attack—looking at you, Starbucks.

Once the parades and rainbow-branded merchandise disappears, our Queer, Trans, Black communities are left to fend against the combination of racism and anti-LGBTQ2S+ discrimination in housing, employment, policing, and more.

The experiences of Black LGBTQ2S+ people are only centered when one of us is killed—and the public outcry always fades before any noticeable change is implemented.

Look no further than Titi Gulley, a houseless Black trans Portlander who was found hanging lifeless from a tree in Rocky Butte Park on Memorial Day last year. If Black trans lives really did matter, Titi would be alive today, with safe and stable housing.

The work for intersectional LGBTQ2S+ justice is not over. Oppression doesn't disappear when the headlines go away. We're not done fighting until every single one of us has the ability to not only survive—but thrive.

Earlier this month, we founded the Black Resilience Fund, and it serves as a reminder to the broader LGBTQ2S+ community that our liberation is interconnected.

We must show up together against all forms of injustice if we're ever going to reach a future where we are all seen, accepted and loved.

So for us, Pride is still about fighting for our lives.

Leila Haile, Co-Founder of Ori Gallery

Pride this year is about continuing the work of our Trans-African elders and the legacy of the Compton's Cafeteria Riot and countless uprisings before Stonewall. They knew, as we know now, that nonviolence only works against an enemy that has a conscience, and that our oppressors have none.

Pride is about the act of revolutionary love, and the justice we seek is an integral part of that love. Dismantling institutions built with the blood of colonized people is the ultimate act of love. All of the anti-bias training on the planet will not get us free—it is up to each one of us to decide how we are going to become the grains of sand that brings the machine of white supremacy to a halt.

Lilith Sinclair, Activist

As an Afro-Indigenous, queer, femme, nonbinary sex worker and abolitionist, I personally know this to be true: Black, Brown and Indigenous abolitionists and organizers have been preparing years for this moment.

Pride 2020 is about revolutionary Black queer abolitionists of this generation breaking through the glass ceiling of a white supremacist government to demand Black liberation. We share an understanding that prioritizing Black liberation and de-colonialism means the abolition of not just the police, but the entire imperialist, white-supremacist, colonial, racial capitalist system that protects killer cops.

I see the moment we exist in as an opportunity to learn from some of our most intersectional organizers—those who see not only the need for our fight, but the risks at stake, the care we need and the systems we can create outside of an unfair government that was never made to include us.

As Pride Month continues, I hope we prioritize connecting with and supporting the Black and Brown LGBTQIA2S+ community in Portland. It's necessary for us to remember to learn from those who came before us, the ones who have been intentionally kept obscured from history by the education system.

This means we need to fight to honor the legacy of the Black, trans sex-working women who we can thank for Pride Month: Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera. I need white allies who feel safe with cops to remember they can enjoy their comfortable, corporatized version of Pride only because Marsha didn't have any reservations against throwing a brick at the protectors of white supremacy and capitalism.

But we also need to center the Black LGBTQ+ women and femmes whom we have to thank for so many other wins in this intergenerational movement for Black liberation.

We need to talk about Angela Davis, a revolutionary, Black, lesbian woman, political activist, and author. For her story in her own words, I encourage people to check out her biography. The documentary 13th, by Ava DuVernay, is also a great entry point into this history and its relevance to the moment we see before us today.

We must talk about the importance of Black queer visionaries. Our stories must be told by us as oppressed people fighting for liberation. It's why I want people to look up Audre Lorde, a self-described "black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet."

It is critical we as a society uplift Queer, Trans, Black, Brown and Indigenous voices now—especially sex workers, disabled peoples, houseless peoples, our youth and our elderly.

For so many of us, I know that Pride 2020 is about necessity. Pride means disarm, defund and abolish the police and prisons immediately, including U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement—followed by the entire imperialist, white supremacist system it's built on.

Flawless Shade, Drag Performer

"Pride this year is taking it back to what it was originally all about, and the people who fought for us to be where we are today. Usually, how we celebrate Pride is with parades and festivals, and sometimes we lose sight of what Pride actually means. It means being thankful for what you have, and fighting for what you don't have. But I've seen so much more community now than I have at any Pride festival I've ever been to. I'm not getting any governmental help or anything because I'm an independent contractor, so I've had people donating. And when people give you help, you want to help other people, too. So it's been that kind of domino effect. And to me, that's what Pride is all about." As told to Matthew Singer.

Tori Williams Douglass, Anti-Racist Educator and Host of the White Homework Podcast

"I can't separate out who I am—I am female, I am black, and I am queer. All those things are embodied. Because of that, I am very torn with the way companies simultaneously monetize Pride and demonize Black Lives Matter. That's been really hard for me, setting aside COVID and celebrations that would otherwise be happening. Starbucks is the perfect example: Employees are allowed to wear Pride flair, but you're not allowed to wear anything that says 'Black Lives Matter' on it. Well, I'm both, and I'm sure there are black queer people who work for Starbucks. What about them? What about their lives? You can't section people out. I can't take my queerness and set it aside if that makes you more comfortable, and I can't take my blackness set it aside if that makes you more comfortable. This is what I wrestle with every year during Pride. I see big companies monetize this but have nothing to say about me staying alive." As told to Matthew Singer.

Jayy Dodd, Artist

Because it must be repeated: The Compton's Cafeteria and Stonewall protests against police brutality are the catalyst of any understanding of TLGBQ+ Pride. At the forefront of resisting the discrimination and systemic harassment of Queer people nationwide were Black Trans and Queer folks. It was Black Trans women. It was Black Butch Lesbians. It was sex workers. It was not corporations and government officials and once-a-year campaigns.

Can Pride be a pro-Black, pro-Trans, pro-sex work, anti-fascist gathering and celebration? I don't know, but again we are here, commemorating the labor of Black Queer Folk, despite the continued systemic theft and erasure of our lives.

This Pride, I challenge non-Black Queer people to really attend to their investments that kill us. Attend to what parts of Queer culture you can claim without tracing it back to Black people or our radical ways of surviving: language, fashion, references, rhetoric, etc. What have you done for yourselves?

This Pride I challenge straight and cisgender people of all races and ethnicities to attend to the transphobia that resides in their everyday life. Why do you feel entitled to comment about anyone's body?

Lastly, a litany of names to hold. First, my Black Trans kin killed this year alone: Nina Pop. Monika Diamond. Dominique "Rem'mie" Fells. Riah Milton. Tony McDade. Layleen Polanco. And in solidarity with my non-Black Trans kin who have been taken this year alone: Dustin Parker. Neulisa Luciano Ruiz. Yampi Méndez Arocho. Lexi. Johanna Metzger. Serena. Angelique Velázquez Ramos. Layla Pelaez Sánchez. Penélope Díaz Ramírez, Helle Jae O'Regan.

If things do not radically change, you will not know or see any Trans people of color in your lifetime. They are killing us. And y'all miss a parade?

Kathleen Saadat, Activist

Kathleen Saadat has spent most of her life fighting.

Since the 1970s, she has fought for marginalized communities in Portland, whether that's meant for the rights of women, people of color and the LGBTQ community, women's rights, or against police violence. Born in St. Louis, Saadat says she was drawn to the city because of the relatively high number of gay organizers compared to her hometown. She attended Reed College, graduating in 1974 with a psychology degree. A year later, she helped lead Portland's first-ever march for gay rights.

Though she continued to do project work and public speaking engagements after retiring in the early 2000s, she's mostly retreated from view over the past five years. Her last public appearance was last year at the Hollywood Bowl, where she took the stage to sing with Pink Martini—the band backed her on her debut album, Love for Sale, which came out in 2018.

Here, Saadat offers advice to today's protesters, who she believes are doing a good job. LATISHA JENSEN.

WW: Can you talk about your experience advocating against police violence?

Kathleen Sadaat: I've always been outspoken. I was the chair for the Community Oversight Advisory Board. When Kendra James was murdered, I was a part of the group that was raising all kinds of hell about it, including standing up and saying that the district attorney's office was complicit in making sure that the police officers got off.

What sparked your activism initially?

I think on some level it's always been there. When I lived in Nashville, Tenn., back in 1947, I was 7 years old. It was a time when they still had signs on the bus that said, "This section is for colored." I wouldn't sit there when I was by myself on my way to school. Someone told my father about it, and my dad asked me, "I heard you won't sit on the colored section of the bus. Why?" I said because I don't think they get to tell us where to sit because we're colored. He said to me, "You do what you think is right." I think that was pretty courageous for somebody talking to their 7-year-old daughter.

What are your impressions of this current global uprising?

There's a lot of people who have never seen cruelty and have never seen the kinds of things we saw when Mr. Floyd was murdered. They see it in the abstract. But they've been presented with a clear idea of what cruelty can look like. It's different than watching someone get shot. What you saw was a close-up of a human being killing another human being deliberately. When you talk about lynching or burning, it's historical in their minds. It's hard for them to grasp, but here was something in the here and now that they could watch on the TV, and they could hear what was going on in addition to seeing it. I think it struck a chord: "This is what racism really is."

Do you support the tactics being used by today's protesters?

It depends on who you're talking about. I support the demonstrations that are primarily there to teach people, to face their consciousness, to make visible the issue. The tactics used by people who are breaking windows—I'm not interested in that, but I understand them, how somebody could be angry enough to do it. I just don't think it serves a purpose.

What word of advice would you give to young protesters and activists fighting at the front lines today?

Keep in mind that what they're doing means a change for all of us, for everyone who lives in this country. They have to have some understanding how broad and how deep that is, and incorporate that into their thinking. The other thing I would say is, check in with some of the older people sometimes and ask questions. For the older people, don't assume you know something because this is a different world. We didn't grow up in the world that young people live in right now.