After a lengthy renovation and sizable expansion into the former Charles Hartman Fine Art space, the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education has opened the exhibition The Jews of Amsterdam, Rembrandt, and Pander.

At first glance, the far-flung cityscapes drawn by the 17th century Dutch master and painted by recently deceased PDX transplant Henk Pander may seem unlikely choices for a gallery honoring the Oregon Jewish legacy. According to OJMCHE adjunct creator for special exhibitions Bruce Guenther, though, the artists share far more than just hometown ties to the Netherlands.

“This exhibition is a way of place and identity and sociopolitical history coming together through the visual arts,” Guenther says.” We look at the presence and absence of Jews in Amsterdam over a 400-year history through the eyes of two nonpracticing Christians who made work grounded in the Jewish community experience at times of major changes.”

Rembrandt van Rijn lived and worked among a swiftly blossoming Jewish population drawn by the booming Dutch economy and newfound promise of religious freedom; Henk Pander, born in the Amsterdam suburb of Haarlem, grew up during the Nazi occupation and aftermath of the Holocaust. By examining each artist, Guenther tells WW, we come to develop our own greater understanding of past grandeur and all that was lost.

WW: How’d this all begin?

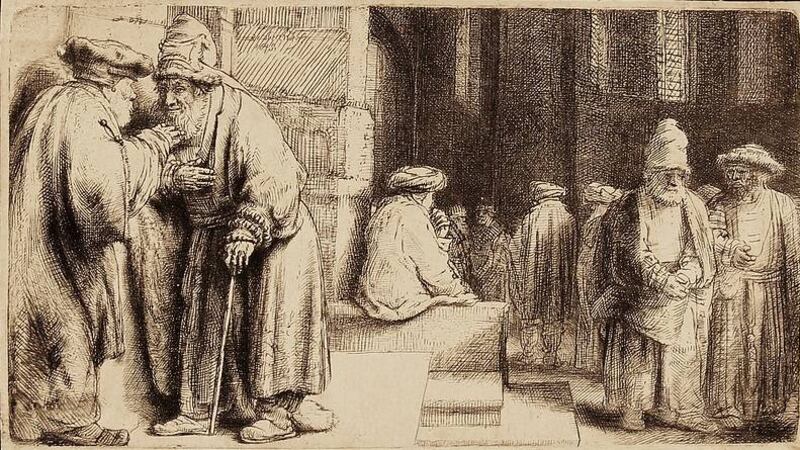

Bruce Guenther: Before COVID, the museum’s small print gallery had planned to show this group of prints assembled by a couple who collected Rembrandt’s [works]. [Museum director] Judy [Margles] asked if we could still do the show but make it more interesting, more engaging, and I said that we had a chance to change the narrative from just looking at another set of etchings. They’re beautiful impressions, but if we talk about Rembrandt observing Amsterdam as the home of a Jewish community, we can make them tell a story.

This was the Dutch golden age. It’s the first time in European art when Jews were represented in all their humanity and not as the devil incarnate or evil Shylock. Amsterdam becomes a very important place economically, intellectually. The city quadruples in size from 1600 to 1621 when Rembrandt moves there and buys a home in the Jewish community where he’ll live for 21 years.

We have a painting of that same house by Henk Pander in the second half of the exhibition—the moment in the 20th century when massive sociopolitical events change Amsterdam’s Jewish community.

He was aware that it was Rembrandt’s house?

Very aware. He comes from a family that’s at least four generations of artists, and his father was nationally known as an illustrator of books. He’s born in 1937, goes to the Rijksakademie, in which Rembrandt studied, and lives in post-war Amsterdam, where the buildings still stood vacant because 140,000 human beings, the entire Jewish population who hadn’t escaped, were deported to the death camps.

Henk Pander was 3 years old when the Nazis marched into the Netherlands. They were trapped inside of Amsterdam during the bombings and air fight over the city. His father was briefly arrested, and the family almost starved to death. He had vibrant firsthand visual and emotional memories of witnessing the Haarlem synagogue be destroyed and friends of his father disappear because they were Jewish.

The paintings are recent, though?

Henk started these works in 2018. The ones we’re showing, about two-thirds of the series, are specifically about the streets of Amsterdam and the Jewish neighborhoods. He had an image in his head, he had the photos of the street today, and he reanimated those with the weight of history and a sense of loss from personal experience.

Did the gallery’s expansion play any part when assembling the exhibit?

In the [museum’s] center, we’ve created an intimate space for the etchings—a celebration of humanity for this 17th century golden age. Outside that space are the buildings left as empty shells.

These are not bombastic pictures like Rembrandt’s reflection of the Jewish community’s prosperity. Henk’s paintings speak in a whisper. It’s not about bodies. They’re subtle paintings of anguish and horror. They are also, by the way, beautiful—60 by 70 inches, oil on canvas, lusciously painted. Henk was a colorist, and the paintings sing.

You see [in the paintings] that a street’s not simply empty. It’s a dead street that once was alive. The buildings Henk Pander observed reveal the history of the horror but so subtly that it takes two or three visits to notice the windows are darkened and by the side of the door a chair lies broken. In one painting, there’s rain, and it looks like the building’s bleeding.

Henk liked to talk about being a contemporary history painter. After the fall of the World Trade Center, he went to New York, spent two or three weeks drawing the wreckage, and made a spectacular painting. With all that, he was trying to do what artists have historically done: see and process the chaos of history passing. And engage with the emotional and spiritual continuance of humanity.

SEE IT: The Jews of Amsterdam, Rembrandt, and Pander exhibits at the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education, 724 NW Davis St., 503-226-3600, ojmche.org. 11 am-4 pm Wednesday-Sunday, through Sept. 24. $5-$10. Members and children under 12 free.