The first important thing about making plutonium is that nobody notices.

That was the baseline condition on Army Col. Franklin Matthias’ checklist when he arrived at a bend of the Columbia River outside Richland, Wash., around Christmas of 1942. He was searching for a remote location to build a factory that would produce the plutonium J. Robert Oppenheimer needed to construct an atomic bomb. Matthias’ last stop on his hunt for a Manhattan Project site was this arid steppe known as the Hanford Reach.

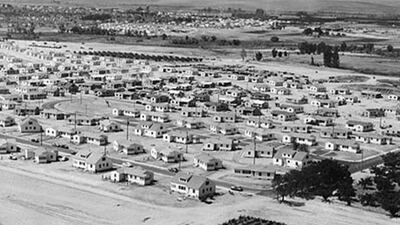

A nuclear reactor is not easy to hide. But surround it with 586 square miles of desert and it’s harder to spot. Within months, 40,000 construction workers arrived at the Hanford Site from around the country, and a town sprang up around them: thousands of prefab houses and aluminum trailers, a barbershop and a movie theater, an automated doughnut machine making 18,000 doughnuts an hour. Their work product was the B Reactor, a concrete monolith that started churning out radioactive rods in September 1944.

It was imperative that the Axis powers not discover the project; most laborers and engineers working on it didn’t know what it was, either. The secret came out Aug. 6, 1945, the day a nuclear weapon was dropped on Hiroshima. The Pasco Herald trumpeted: “IT’S ATOMIC BOMBS.” Three days later, Fat Man—a round metal tub filled with Hanford’s plutonium—incinerated Nagasaki. The Richland Villager rejoiced: “PEACE! OUR BOMB CLINCHED IT!” Other, more complicated feelings would emerge later.

A framed, yellowed copy of that Villager edition hangs on the wall of Xenophile Bibliopole and Armorer, Chronopolis (2240 Robertson Drive, Richland, 509-375-7505, xenophilebooks.com; 11 am–5 pm Thursday–Saturday). This bookstore, dropped in a dusty industrial park, contains Steven Woolfork’s collection of pulp magazines, the largest west of the Mississippi River, plus a room of midcentury curios—a baseball pennant that reads “Hanford Atomic Works,” a varsity jacket embroidered with a green mushroom cloud—salvaged from Richland, a company town where the company built America’s nuclear stockpile.

Xenophile must be the most unlikely national park gift shop in the country. Because it sits two blocks from the headquarters of Manhattan Project National Historical Park (2000 Logston Blvd., Richland, 509-376-1647, nps.gov; 8 am–4:30 pm Monday–Saturday), the science-fiction bookseller also carries a display of T-shirts and hats proclaiming that the wearer has visited the birthplace of the atom bomb.

That bizarre juxtaposition hints at the scorched, sunny strangeness of a nuclear wasteland that has become a tourist magnet. Hanford is no longer a government secret: The buzz around last year’s Oscar-winning movie Oppenheimer multiplied public interest in the Manhattan Project and the three national historical parks that memorialize it. In 2023, eight years after the National Park Service began operating at the Hanford site, 13,000 people toured the B Reactor.

There remains something otherworldly about the Hanford Reach, an immense expanse of rock and sagebrush where the last free-flowing stretch of the Columbia briefly runs north before turning toward Oregon, its banks dotted every 20 miles with mothballed reactors—their slanted roofs looking like the result of an atomic barn raising. A visit here is a plunge into the history of World War II and the Cold War, but it is also a trip to something more alien and frightening. Hanford is where Americans, summoning their pluck and optimism, tampered with the building blocks of the universe to construct weapons that would vaporize cities, send generations of schoolchildren hiding under desks, and poison the land selected for the project.

Heavy stuff. Best to make a plan before you go.

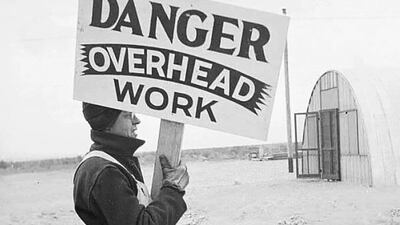

Any itinerary at Hanford orbits around securing a seat on the tour buses that travel 38 miles, twice a day, from the National Park Visitors Center to the B Reactor. That isn’t as daunting a prospect as it used to be. A decade ago, those free seats were distributed by lottery; increased demand caused the U.S. Department of Energy’s contractor to increase the frequency of tours, and now prospective visitors can score reservations a month in advance on the website of Manhattan Project B Reactor Tours (manhattanprojectbreactor.hanford.gov). Tour dates for this August, for example, go live July 1. There is a sternly worded warning about radiation exposure.

A 45-minute ride amid air conditioning and informative docent patter deposits you at the reactor, a pile of gray concrete with a smokestack. A hallway marked by spinning red alarm lights leads to the face of the reactor. Rows of folding chairs face the machine, like a grange hall set up to behold an occult ceremony. The reactor block is a cast-iron wall, 40 feet tall, honeycombed by gleaming tubes where engineers once inserted uranium slugs to bombard them with neutrons and create plutonium. For scale and impact, it rivals a cathedral. It’s a difficult sight to describe further without reaching for analogies from silent movies and comic books. I can tell you that the first time I saw it, I started to cry.

The rest of the facility is standard 1940s mad-scientist stuff, with a doomsday vibe and a nice coat of seafoam-green paint. The clock above the control room desk is frozen at 10:48 pm: the moment in 1944 when the reactor went critical. Cheerful signs illustrated with Ziggy-like cartoon characters remind workers to extinguish their cigarettes and leave when an evacuation horn sounds. Every 20 minutes, docents offer short lectures to unpack atomic theory—the field trip at the end of the world.

After contemplating fission on the quiet bus ride back, you may want a drink. Good news: The visitors center shares its building with two bars, one of which is Bombing Range Brewing Company (2000 Logston Blvd., #126, Richland, 509-392-3377, bombingrangebrewing.com; 11 am–9 pm Monday–Thursday, 11 am–10 pm Friday–Saturday, 11 am–8 pm Sunday). It serves an excellent hefeweizen, and the brewery’s name offers a clue to the attitude Richland adopts toward its nuclear parentage. “We are proud of the mushroom,” a resident told the Spokane Spokesman-Review in 2017. “If people make an issue of it, they need to do something else.” There’s plenty to do: Richland also hosts an Atomic Ale Brewpub, a bowling alley called Atomic Bowl, and a pleasant, newish wine bar named 3 Eyed Fish Kitchen + Bar (1970 Keene Road, Richland, 509-778-5546, 3eyedfishwinebar.com; 11 am–8:30 am Monday–Tuesday, 11 am–9 pm Tuesday–Wednesday, 11 am–10 pm Thursday–Friday, 10:30 am–10 pm Saturday, 10:30 am–8:30 pm Sunday). It has a selfie wall.

While your timing hinges on when you score a reactor tour ticket, to get the most out of Hanford stop first at the REACH Museum (1943 Columbia Park Trail, Richland, 509-943-4100, visitthereach.us; 10 am–4:30 pm Tuesday–Saturday; $12). The museum’s galleries provide a helpful primer to the ecology of the Hanford Reach (whose bluffs and ridges were deposited 13,000 years ago by the Missoula floods that carved the Columbia River Gorge) and the much more condensed history of the Manhattan Project, which defined the region in three years and planted roots for another four decades of the Cold War, as the feds expanded the reactor count to nine. Like most exhibits in Richland, the REACH Museum tries gamely to grapple with the destructive power of the bomb, but only obliquely discusses the death toll in Japan, the effects of radiation on the land—Hanford is now the nation’s most expensive environmental cleanup by a wide margin—and the “downwinders” whose children were poisoned by the monster at the edge of town.

Oddly, or maybe obviously, the closest a tourist can come to understanding the immensity of what happened here is to drop the reading and walk out into the desert. The Hanford Site itself is closed except in the three-hour increments provided by guided tours, but on the opposite bank of the Columbia it is ringed by Hanford Reach National Monument (64 Maple St., Burbank, 509-546-8300, fws.gov). These 196,000 acres of shrub-steppe are home to burrowing owls, porcupines, and the Hanford elk herd. The monument offers a hiking paradox—no official or maintained trails, but in some units of the desert, walking is allowed anywhere (bring water). An hour’s drive from Richland will get you to a footpath called White Bluffs North. Here, the land gently rises to offer a view of the river, the reactors, and a moonscape that human beings, for all our ingenuity, have not yet managed to destroy.

This story is part of Oregon Summer Magazine, Willamette Week’s annual guide to the summer months, this year focused along the Columbia River. It is free and can be found all over Portland beginning Monday, July 1st, 2024. Find a copy at one of the locations noted on this map before they all get picked up! Read more from Oregon Summer magazine online here.