If modern-day Portland has an origin story, it might just be the strangling of the Mount Hood Freeway, which officially died at the hands of U.S. District Judge James Burns in 1974.

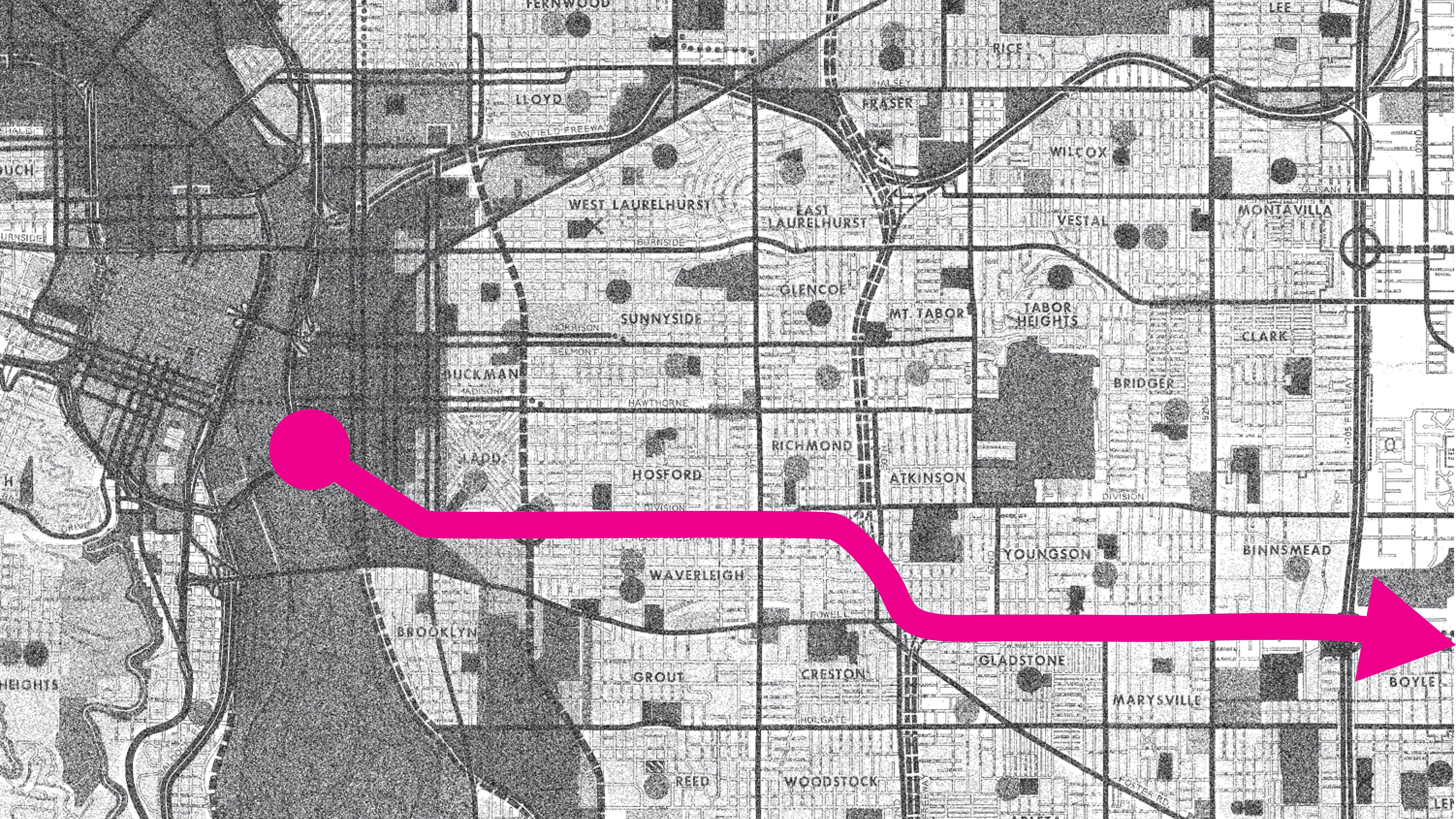

Burns signed a death sentence for a highway that would have plowed through Southeast Portland along Powell Boulevard, connecting the Marquam Bridge to 122nd Avenue and carving up half a dozen neighborhoods. It had been on the drawing board since 1943, when Robert Moses, the mad genius behind New York City’s highway system, drew up a plan for Oregon and Southwest Washington.

The Oregon Department of Transportation built other highways first—bulldozing neighborhoods to pave Interstates 5 and 84 and the Interstate 205 and 405 ring roads.

But by the time ODOT got serious about the Mount Hood Freeway in the late 1960s (the agency bought right of way and began demolishing houses), things had changed, says Ethan Seltzer, professor emeritus of urban studies and planning at Portland State University. Portlanders had witnessed the destruction of neighborhoods that earlier interstate construction caused; the environmental movement was taking hold and something close to revolution was in the air.

In the teeth of support for the project from business and labor from business interests, activists leveraged new federal laws, including the Clean Air Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, to challenge the freeway in court. As a capper, the insurgents, led by Mayor Neil Goldschmidt, convinced the federal Department of Transportation to divert money from the freeway to light rail, later named the Metropolitan Area Express, or MAX. “It was a remarkable and really amazing achievement,” Seltzer says. “It came at a time when the federal government was funding sprawl and the growth of suburbs through the interstate highway system, and the future of cities—including Portland—was unclear.”

The death of the Mount Hood Freeway came amid a flurry of other historic progressive policy victories: Portland tore up the six-lane Harbor Drive expressway along the west bank of the Willamette River and built Tom McCall Waterfront Park. At the state level, lawmakers passed the Bottle Bill, created urban growth boundaries, and passed a groundbreaking public records law.

Seltzer says the era marked an upswing in effective activism that made Portland a magnet for people from all over the country who wanted to bring about change.

“Portland was a pretty sleepy, insular place in the 1960s,” Seltzer says. “What the death of the Mount Hood Freeway showed is that in Portland, a small group of people can have a huge impact.”

Next Story > 1975: Will Vinton

Opens in new window

Opens in new window